Description:

John Blackthorne, an English ship pilot, whose vessel

wrecked upon the Japanese coast in the early 17th century is

forced to deal with the two most powerful men in Japan in

these days. He is thrown in the midst of a war between

Toranaga and Ishido, who struggle for the title of Shogun

which will give ultimate power to the one who possesses it.

***

Journey to the brutal, thrilling world of 17th century

feudal Japan with SHŌGUN, the unforgettable adventure

based on the bestselling novel from James Clavell. Winner of

three Golden Globes and three Emmys, the three-part

miniseries starring Richard Chamberlain arrives for the

first time on stunning Blu-ray July 22 from CBS Home

Entertainment and Paramount Home Media Distribution. The

sweeping story of love and war follows John Blackthorne

(Chamberlain), an English navigator shipwrecked off the

coast of Japan. Rescued, he becomes an eyewitness to a

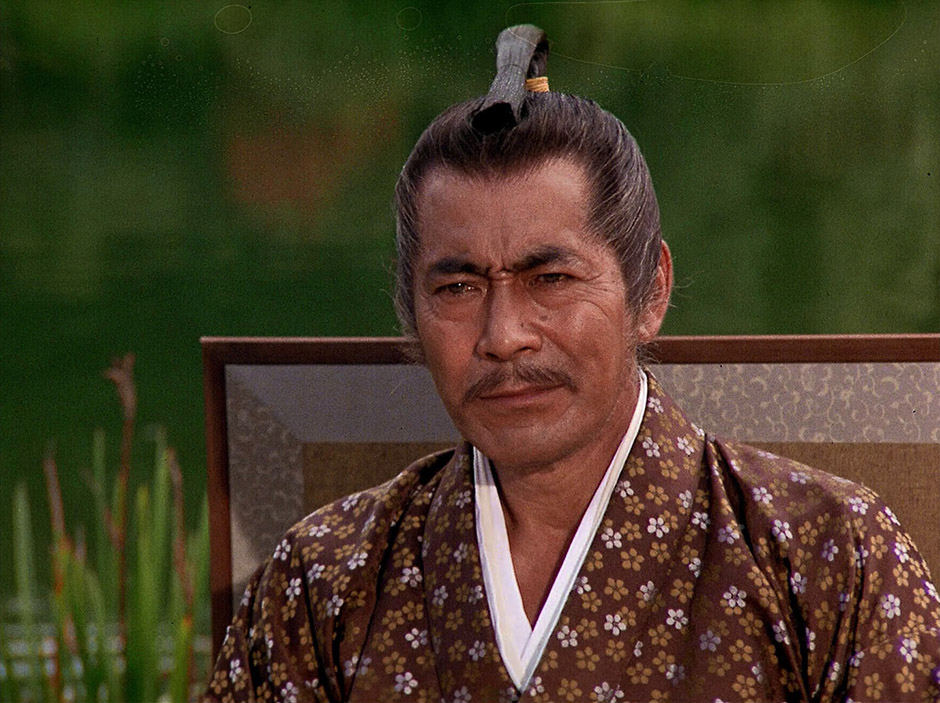

deadly struggle involving Toranaga (Toshiro Mifune), a

feuding warlord intent on becoming Shogun – the supreme

military dictator. At the same time, Blackthorne is

irresistibly drawn into the turmoil and finds himself vying

to become the first-ever Gai-Jin (foreigner) to be a made a

Samurai Warrior.

The Series: 9

Critical Reception [Wikipedia]:

The miniseries was sparked by the massive success of the

television miniseries Roots (1977) that had aired on the ABC

Network in 1977. The success of Roots, as well as the

critically acclaimed TV miniseries Jesus of Nazareth (1977),

would spawn many miniseries onward through the 1980s. Shōgun,

which aired in 1980, also became a highly rated program and

continued the wave of miniseries over the next few years

(such as North and South and The Thorn Birds) as networks

clamored to capitalize on the format's success.

The success of the miniseries was credited with causing the

paperback edition of the novel to become the best-selling

mass-market book in the United States, with 2.1 million

copies in print, and increased awareness of Japanese culture

in America. In the documentary The Making of 'Shōgun', it is

stated that the rise of Japanese food establishments in the

United States (particularly sushi houses) is attributed to

Shōgun. It was also noted that during the week of

broadcast, many restaurants and movie houses saw a decrease

in business. The documentary states many stayed home to

watch Shōgun—unprecedented for a television

broadcast.

The Japanese characters speak in Japanese throughout, except

when translating for Blackthorne. The original broadcast did

not use subtitles for the Japanese portions. As the movie

was presented from Blackthorne's point of view, the

producers felt that "what he doesn't understand, we

understand.” Rotten Tomatoes gives the series a critic

rating of 80%.

Reviews:

Time Out London:

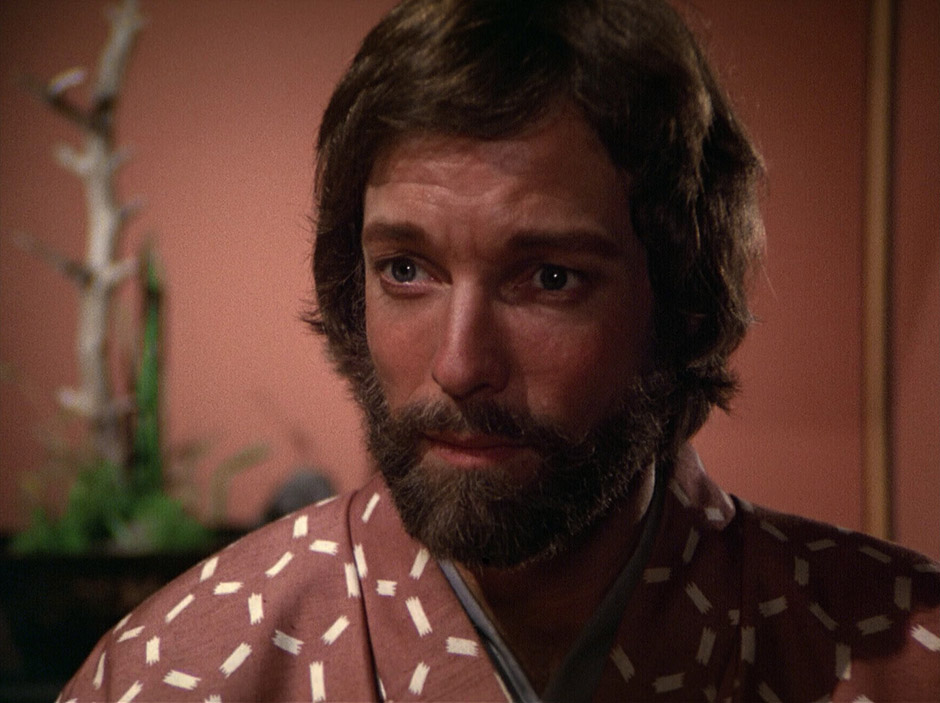

Startled blue eyes above silky beard, Richard Chamberlain in

a kimono looks more like an actor on his way to the bathroom

than a grizzled English seafarer, cast ashore in 17th

century Japan, where he turns samurai and becomes

romantically and actively involved in a violent political

intrigue. Based on James Clavell's huge novel, Shogun

was originally a 10-hour TV mini-series. Shamefully hacked

down to 151 minutes (still a yawning long haul), the plot

has been rendered action-packed but utterly

incomprehensible. Though production credits and cast point

to a lively synthesis of oriental/occidental interests, the

end result reduces the complex moral codes of feudal Japan

to an inexplicable death wish. The threat of harakiri

follows Chamberlain's illicit hanky-panky with the Lady

Mariko (Shimada) as surely as day follows night, and yet

again that rising sun blobs onto the screen like a pulpy

tangerine.

eFilmCritic.com -

One of the best things about a quality mini-series is quite

simply that of sheer volume; if you're having a great time

with the first hour of Shogun, lucky you! There's

over eight more hours to enjoy! And you'll have to search

far and wide to find a made-for-television production that

boasts this sort of quality. The costumes, the set designs,

the majestic Maurice Jarre score, and the obvious respect

for even the smallest cultural detail of 17th century Japan

combine to create an entirely engrossing, not to mention

lengthy, tale. That the viewer is not even offered subtitles

when the Japanese characters speak is an indication of the

respect the filmmakers have for their audience; those who

are paying attention simply won't need the subtitles in

order to follow the drama. With his performances in Shogun,

The Thorn Birds (1983), and a handful of other (less

celebrated) mini-series, Richard Chamberlain became known as

the king of multi-chapter TV dramas, and his work here

represents some of the finest of Chamberlain's career. And

of course you can expect nothing but a truly regal presence

when you have Toshiro Mifune as your intensely noble feudal

warlord. - Scott Weinberg

PopMatters.com:

Everything about Shogun is big and impressive, from its

running time (nine hours) to the large cast, superb location

shooting, and obvious care taken with the sets and costumes

(the castle sets were constructed using traditional peg and

groove methods; every kimono was unique). The story is set

in a crucial period in Japanese history as nearly 150 years

of civil unrest were about to come to an end with the

establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1603. . . Despite

being filmed entirely in Japan and featuring an impressive

cast of Japanese actors. . . Shōgun is concerned primarily

with Blackthorne’s story while the distinguished Japanese

cast is reduced to being supporting players in the heroic

tale of a white guy making good in a foreign land. . . [and]

while the Japanese characters behave as if they were living

in the period of the story, Blackthorne appears to have

popped out of a time machine, because his values are more

typical of the late-20th century than the early-17th. -

Sarah Boslaugh

LensView

1980 - The year I bought my first VCR - a Sony Betamax. I

wanted it expressly to record this series, which for reasons

I have since forgot, imagined would be a keeper. And so it

was, allowing me to watch the entire series again about the

time that it went into syndication, which loped off a couple

hours of program and substituted Jane Alexander for Orson

Welles as Narrator. Eventually, my copy became unwatchable -

not from overplay, as it happened, but from underuse. Much

the same fate awaited more titles in my library than I care

to admit. It was not 2003 that Paramount brought out a

proper DVD of the original broadcast plus some pretty good

bonus features, all of which are on this Blu-ray edition as

well, though, sadly, not upgraded to HD in any way. The DVD

image was good and the sound quality passable, no worse than

I remembered my Beta copy to be, but the new Blu-ray, while

apparently struck from the same source as the DVD, betters

it in small ways which, accumulatively, make for a more

satisfying viewing experience.

There was a curious gap in my television watching history: I

was present during its earliest years, but absent all

through college and beyond, from 1960-1972. I mention this

because I didn’t really know from Richard Chamberlain all

that much. I never watched Dr. Kildare. Still haven’t, and

not likely to. He always struck me as trying too hard to

impress. Still, he had a certain charisma, a kind of

commanding presence despite his relatively light frame and

his reliance on intensity. Not having read the book, and

knowing Japanese actors primarily through Toho films,

especially the always impressive Toshiro Mifune, what I was

not prepared for was Yôko Shimada. Totally unknown to me

prior to Shōgun, Shimada absolutely swept me off my

feet, as she did Blackthorne, with her directness, grace,

innocence and oriental beauty.

Shimada first appears at Toranaga’s bidding from a hidden

door of sorts, gliding past Mifune to rest just alongside

and behind him. A simple move, but one that relays to us,

however subliminally, the relationship her character has to

Toranaga and to Blackthorne, something that the Englishman

never quite comes to terms with - until it is too late. This

is perhaps the most carefully prepared scene in the drama,

one that director Jerry London lingers on at length to allow

the dynamics, however subtly portrayed, to sink in for his

audience. It comes near the end of the second hour where

Blackthorne is finally presented to Toronaga following a

series of interactions with local island leaders,

incarcerations and transports to various locations. Unlike

the village where Blackthorne first awakens to his local

hosts, Toronaga’s castle is an exalted piece of work, both

in terms of sheer elegance and mystery. Blackthorne has been

until now utterly dependent on intermediaries of the “enemy”

- he, English, Anglican; they, Portuguese, Jesuit &

Catholic.

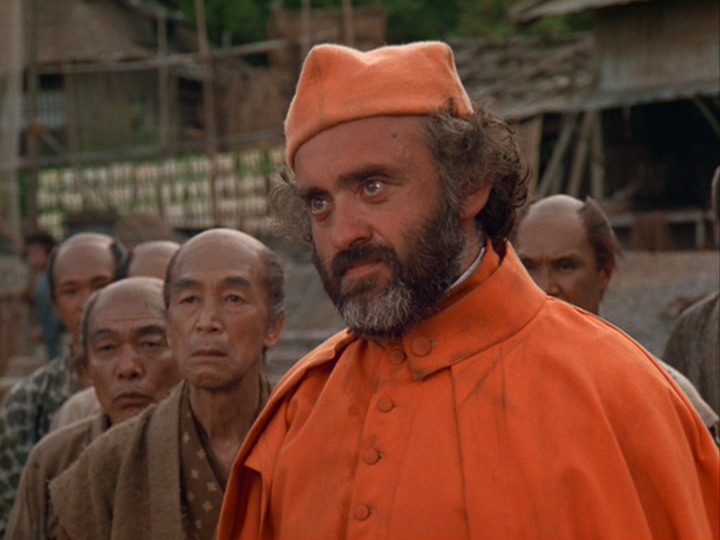

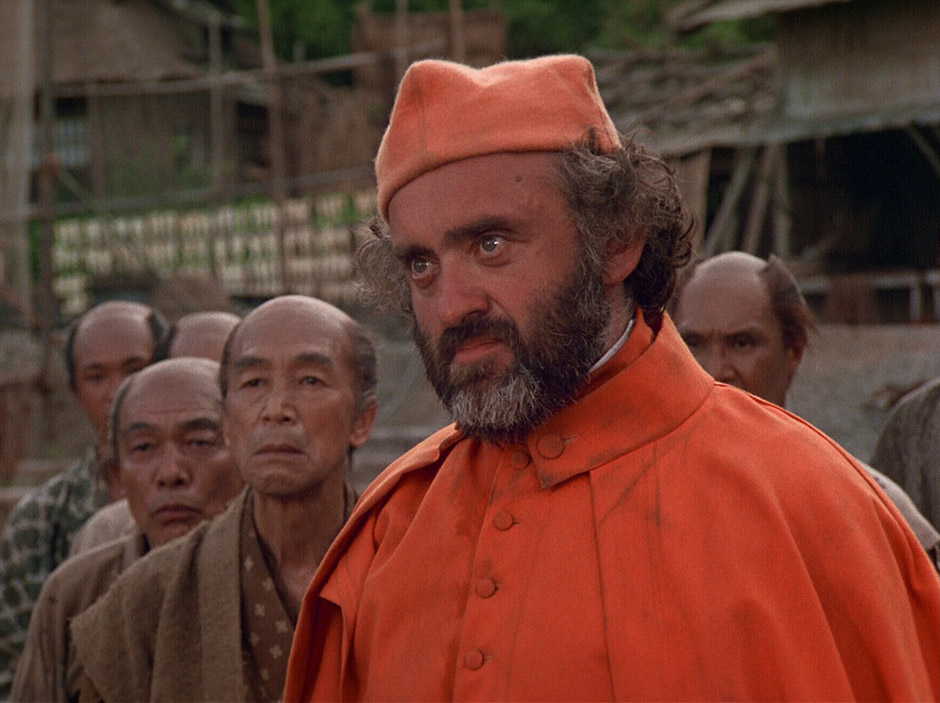

Father Martin Alvito (Damien Thomas) sits about halfway

between Toronaga and Blackthorne and well off and to the

side, permitting a clear view by all the participants.

Father Alvito proposes himself as translator, but

Blackthorne insists that he does not trust him to act for

him. As if by magic, at the mere ring small bell, Toronaga

produces Lady Toda Mariko (Shimada), whom Blackthorne

accepts as translator, not only because he sees no reason

not to but because he is blinded by her presence. He is also

blinded to the fact of what she is doing at this moment,

which is to whisper her translation of Blackthorne’s words

into Toronaga’s ear, a fact that Blackthorne accepts as mere

formality. However, it is much more than that. Not that she

is distorting his meaning but that Blackthorne sees her as

apart from Toronaga and in relation to himself when the

reverse is more the case.

What Blackthorne fails to see is that Toronaga anticipated

the Englishman’s mistrust of Alvito, a man who presents

himself to Blackthorne as having Toronaga’s confidence, and

had Lady Mariko waiting for just this reason. Mariko, in her

way, is just as strategically important to Toronaga as

Alvito has been, and Blackthorne will become. Toronaga is

fully aware of her story, her pain and her loyalty, all of

which glides past Blackthorne with her very entrance on the

stage, just as the sliding doors move in every home and

castle.

Reviewers are often quick to point out that the Japanese

characters who do not speak English (almost all of them in

this case) are not subtitled so as to further “our”

identification with Blackthorne’s plight. For our part, we

have endured the stranded seaman’s various humiliations,

mutually incurred insults, threats of death to himself and

his surviving crew. We - meaning: the English speaking

audience - identify with him and, once he gets past his

initial posturing just this side of fanatical fervor, he

sees in Lady Mariko a respite and oasis from his journey. It

must be seductive and unnerving in equal measure that she

does not lower her gaze in feigned embarrassment as other

women commonly do - or did, even Europeans, I assume -

unless they have designs. Naturally, he falls in love with

this oasis or should I say: mirage, with consequences

predictable to a Japanese audience, but not to us. . . which

leads us to the most intriguing and most profound aspect of

this drama: translation.

From the moment he awakens to the “Japans” Blackthorne is

thrust into a situation not unlike that of a person who

suddenly loses their sight. He depends on others to find his

way, even to survive – add to this the responsibility he

feels for his crew – yet he trusts no one. As the worst

possible luck would have it, the very first person he comes

across that speaks English and Japanese is a Jesuit priest

who sees Blackthorne as mongoose to his cobra, or

vice-versa, depending on who has the upper hand – nearly

always the priest. There is a moment a little later on that

ripples throughout the story in which Blackthorne becomes

aware of, and gives expression to, his dis-ease by demanding

that his translator makes clear to his captives that he does

not trust him to translate for him. Blackthorne’s

predicament seems unresolvable – yet he cannot simply

tolerate the crisis. You would think the matter could be

resolved rationally, but the concept of “natural enemies”

seems ordained from Genesis, as resonances in this story

with Biblical and present day Middle East are enough to make

you cry. We, the audience, must ask ourselves at this point

and at countless times throughout the drama, what we would

do and say in a similar position.

Just as writers Clavell & Bercovici and director London

invite the audience to learn something of seventeenth

century Japanese language and culture, Toronaga wants the

same of Blackthorne to the extent this is possible and

permitted. Toronaga instructs Mariko to be the Englishman’s

teacher and for a considerable part of the story they have

interchanges of unusual lyricism that are nothing short than

the language of love, all the more tender because of its

contrast to Blackthorne’s previous interactions on this

island, save the Portuguese pilot, Rodriguez. (The intimacy

and attention this form of interaction requires makes for an

effective template we see in the kind of here and now

communication that has become so popular in recent decades.)

As the Englishman becomes more fluent he comes to an

interesting crossroads: whether or not to revert to his

former style of personal power politics. In the beginning we

see Blackthorne as a man who places his pride - of self, of

country, of religion - above all else, even the safety of

his crew. As he falls in love with Mariko, as with all men

in such a state, his pride gives way to adoration – both

slippery and dangerous slopes – and as he becomes fluent in

her language he deceives himself that his understanding of

her is equal to his command of the language. Because he

wants what he wants, he feels she will comply with his

desires, an illusion that men have of women so basic and

primal that only tragedy can result, a misapprehension

familiar to us all.

Image:

8

NOTE:

The below

Blu-ray

captures were ripped directly from the

Blu-ray

disc.

I expect there will be those who will come down on this

Blu-ray

for not being HD full frame - i.e., 1.78:1 - but despite

being shot on 35 mm film and, as I recall, matted for

potential theatrical presentation, what we have here is the

aspect ratio as we saw it 1980, except that the film has

been rescanned for high-definition viewing. Paramount’s DVD

edition was already very decently color corrected with good

contrast control and noise spec’s. I would have said there

was nothing about that image, unlike its lackluster audio

mix, that cried out for renewal on standard definition

terms. All the same, the new hi-definition transfer is

improved, if not by leaps and bounds. Despite its softness,

the image suggests the motion picture film from which it was

struck and, as such, must look more impressive than on its

original outing on television over thirty years ago.

Density and resolution is very good, with facial textures

and fabrics like the shoulder roll on Blackthorne vest and

the fine silk of a kimono or the metallic ornamentation of

the Japanese headgear, come through wonderfully – not so

much that they bring attention to themselves, but that they

offer a tangible reality merely suggested by the DVD. Color

is of a similar palette as the DVD but a bit less murky and

a skosh brighter and deeper. Contrast, especially in outdoor

scenes where there are light values across a wide spectrum,

are just about perfect, showing off what well composed and

properly lit 35 mm photography can do. There are no transfer

anomalies or enhancements to get in the way. Noise is pretty

much non-existent and the picture looks wonderful projected

in motion and standing still onto a large screen. There are

a very few fleeting patches of bewildering mushiness and the

occasional source damage (see top of the frame of #30) that

we wouldn’t have expected to be repaired. I observed that

the difference between DVD and Blu-ray is seen to better

advantage projected with my JVC RS-57, which likely benefits

from some extra judicious processing, than my iMac display,

which only slightly exceeds HD spec.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()