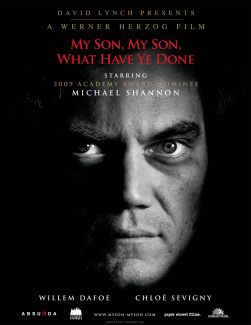

Based on a true story about a

promising young actor (Mark Yavorsky, in 1979 a student at

UC-San Diego) whose character in the play he was in kills

his mother. One day he walked out of the play and went home

and continued the performance.

The Movie: 6

Ordinarily we don’t think of the films of Werner Herzog as

comedy. Quite the contrary. In movies from Aguirre the

Wrath of God and

Fitzcarraldo, to Grizzly Man, Herzog explores

the dark side of human nature, that part of us that drives

us to impossible goals and, in some cases, enables us to

overcome impossible odds. It’s not that a typical Herzog

film is entirely bereft of humor (witness his version of

Bad Lieutenant) but comedy has not, up until now,

been so much in the foreground. For how else are we to

understand and respond to My Son, My Son, What Have Ye

Done, a title with a curious rhyming lilt that could

portend a punch line as much as tragedy?

On the face of it, the subject, matricide, is hardly a

joking matter. If we were to attend only to the dialogue,

the movie would appear to explore seriously how such a deed

might have come about, but in Herzog’s hands, the result is

quite different - emotionally detached, as are we, from the

deed, its perpetrator and the effect on those closest to

them. This may be no coincidence. As Herzog himself observes

in the bonus feature “Behind the Madness” when he met

Yavorsky to research his subject he found him quite scary

and decided there and then that his movie would not closely

follow the life and times of the real-life protagonist.

Perhaps Herzog went further in that direction than he meant

or perhaps the film represents a new path for him.

As I watched this strange movie - more, I thought, David

Lynch than Herzog - I wondered if I were an architect in

1949 when the movie of The Fountainhead came out, if I would

be so distracted by questions about the designs used to

represent this or that intention of the protagonist that I

would be unable to assess or enjoy the film as drama, or

metaphor, or whatever. For psychology being my profession,

such was the case here.

Michael Shannon plays Brad McCullum, a man, not so young

that his girlfriend can’t help but remark that he still

lives with his mother (Grace Zabriskie) after thirty-odd

years and caters to her every whim. While this might contain

the seed to explain his murderous act, Herzog wants to tie

in two other events: a kayaking adventure in Peru that left

five of his friends dead, and the classic Greek play he had

been rehearsing, “Orestes” where the title character, played

by Brad, kills his mother in order to put an end to a larger

cycle of generational killing.

Herzog and co-writer Herbert Golder are careful not to show

us the “pre-morbid” Brad. The story proper is told in

flashback interviews, post-Peru, with the fiance, the

director of the play and an eyewitness to the murder who

says that Brad was “changed” by the incident in South

America. Changed from what, we may wonder? When we watch

Brad and his mother together in these flashbacks we cannot

but assume that their love/hate balance of dependency and

antagonisms have always been that way, and that something

about Peru and Orestes merely tipped a fated scale. Perhaps.

When he returns from Peru, Brad speaks of having had contact

with an “inner voice” that he took as the voice of God

cautioning against joining his friends on an adventure that

to anyone with the IQ of an avocado would have been seen as

suicidal. He has a girlfriend (Chloë Sevigny) of two years

who was planning on marrying him in another few weeks, but

we never see the slightest whiff of affection exchanged

between them. Instead he shares with her his insight as to

the identity of God: the face on a box of Puritan Oatmeal.

(Who knew!) The director of his play (Udo Kier) says he put

up with Brad’s strange behavior because he was talented, but

we see no evidence of that talent. Brad’s mother, on the

other hand, complains to her son that she bought a grand

piano for him but he never plays it.

Not to put too fine a point on

it, Brad is clearly certifiable (as was Yavorsky). While the

temptation is seductive, even overpowering, those who try to

explain schizophrenia in historical, rational terms do so at

their peril. Those close to Brad admit only he was “changed”

when he returned from Peru. Having the results of his

handiwrork, the detectives who arrive on the scene (Willem

Dafoe and Michael Peña) take Brad seriously (Brad has holed

himself up into his house across the street along with two

“hostages”). But then, they hadn’t interviewed him and are

only playing the situation by the book. A correct diagnosis

would not likely have changed their strategy. (More on this

shortly.)

I’m not saying that anyone should have smelled danger about

the “changed” Brad, but the fact that his friends were

willing to make allowances in one form or another speaks

volumes about the kind of social animals we are. I feel that

this is the most reliable dramatic thesis in the screenplay,

yet it is not underscored by Herzog. What’s more, I remain

pretty much unimpressed by any suggestion of cause and

effect relationship between the play Brad was rehearsing and

the matricide, and I doubt that Herzog would say otherwise.

The play and the sword are convenient devices both to mature

and crystalize Brad’s pre-existing insanity and for Herzog’s

narrative. Bad luck for mom. Werner has a field day with it.

So, what’s all this about a comedy! As Roger Ebert tells us

repeatedly, a movie isn’t just about its subject but it’s

about how it’s about its subject. At the risk of seeming all

film-schooly, starting with the opening scene where

Detectives Havenhurst and Vargas joke in the car before they

head off to the murder scene, there is hardly a moment,

aside from the fleeting shot of the corpse floating in her

blood, that isn’t dripping with off-kilter humor. Over here

we have the detectives making the oddest measurements of the

precise placement of coffee cups on a table in the room

adjacent to the murdered victim as if they could have the

remotest importance; later we see them standing in the

street both with their hands up discussing strategy; and

later still, Vargas delivering pizza to a talking garage

door. There’s Brad yelling to the detectives through a

curtain behind a sliding glass door - as the voice speaks,

wizardlike, the curtain moves like he’s breathing directly

into it. Then we have the rehearsals of Orestes where Brad

stands there dazed, brandishing a lethal sword, and all the

director can say is that it’s not a proper Greek sword.

There’s Brad Dourif as Uncle Ted, whose very presence is

pure comedy, assisted by a corral full of world’s largest

bird in one scene and the world’s smallest man in another.

There’s the Peruvian expedition where every man is whacked

out of his mind on some hallucinogenic or other, and where

only Brad has the good sense not to risk having his brains

bashed in by a raging river I wouldn’t dip my toe into – and

even he has to invent an “inner voice” to get himself off

the hook. But nothing compares to mother herself: the

amazing Grace Zabriskie, with cheeks a chipmunk would envy

and a glance of pure reproach. Perhaps you remember her as

the bobbing head that warns Laura Dern in

Inland Empire...

which reminds me again that this movie feels more like David

Lynch than Herzog - and not only because of the pink

flamingos.)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()