Review by Leonard Norwitz

Production:

Theatrical: Protozoa & Phoenix Pictures

Blu-ray: 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment

Disc:

Region FREE

Runtime: 1:48:07

Disc Size: 42,413,320,490 bytes

Feature Size: 28,305,788,928 bytes

Video Bitrate: 28.50 Mbps

Chapters: 28

Case: Amaray Blu-ray case w/ slipcover

Release date: March 29th, 2011

Video:

Aspect ratio: 2.40:1

Resolution: 1080P / 23.976 fps

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC Video

Audio:

English DTS-HD MA 5.1 (48 kHz / 3622 kbps / 24-bit)

Spanish Dolby Digital 5.1

French Dolby Digital 5.1

Subtitles:

English, French & Spanish, and none

Extras:

• Metamorphosis: a making-of documentary (48:50)

• Behind the Curtain - Production, Costume & Ballet (10:30)

• 2 Cast Profiles (6:00)

• 2 Conversations with Darren Aronofsky & Natalie Portman

(5:30)

• 5 Fox Movie Channel Presents (ca. 23 min)

• Theatrical Trailer - in HD

• BD Live

• Digital Copy Disc

Description: Darren Aronofsky's Black Swan, handily

one of the two or three best films of 2010, responds to the

adage: "You can't have your cake and eat it too."

Comparisons to the Powell/Pressburger 1948 classic ballet

film,

The Red Shoes, are inevitable, so right after I saw

the film when it came out in the theatre last year I

scribbled some preliminary fragments of thought before they

escaped me altogether:

In

The Red Shoes, this conflict is represented only

in the ballet itself. Beyond that, the "Red Shoes Ballet" is

merely a metaphor for a struggle which is, in my opinion,

more a projection of Lermontov's psyche than Vicky's. In

effect, it is he, not the dance, that catches up with Vicky

in the closing seconds as she runs out of the theatre. The

case for the struggle being centered in the call of the

dance is obvious, but at the moment, and in the context of

the 1948 film, I am inclined to think otherwise. Or,

perhaps, it is Black Swan that has persuaded me of this

idea.

Lermontov and Thomas (Nina’s impresario) take opposite

positions on the question of integration: "A dancer who

relies upon the doubtful comforts of human love will never

be a great dancer. Never." Perhaps the word "comforts" means

more to Lermontov than it does to Vicky. She merely desires

Love and expects it to be part of what it means to be a

woman. Whereas Thomas feels that Nina cannot dramatize the

part of the Black Swan without having experienced the joys

and pains of love. As he points out to her, she does the

White Swan, i.e. Innocence, perfectly. But her dancing of

the Black Swan lacks any spark of abandon, of sex.

In Black Swan the role of Lermontov is played by Nina's

mother, who insists that her daughter remain a child and

therefore an unintegrated, repressed and conflicted adult.

Like Lermontov, she has hopes that Nina will become a great

dancer, but unlike him, she neither expects it nor demands

it. I think she may actually know, at least at some level,

that Nina cannot be both a great dancer and remain a child,

to wit: when her mother became pregnant with Nina she gave

up a potential, if unlikely, career as a dancer. So as long

as she can keep her daughter from sex, she entertains the

fancy that Nina could have a career.

Poor Nina doesn't have a chance if she shares her mother’s

recipe for success. Her mother takes whatever side is handy

as long as it doesn’t involve boys. She seems sincerely

happy for Nina when she lands the role of her dreams (quite

literally) but at another point, she suggests that dancing

in the quartet of the "Danse des petits cygnes" is not such

a bad thing. But Nina has the bug now, and she must find a

way to rationalize her mother’s commandments with the

instructions of her director.

The Film:

9

It is not surprising that many who see this film take it to

be “about” ballet and what that art form requires of someone

to become a star ballerina. It’s an understanding of the

screenplay that works, if imprecisely and incoherently, as

if David Lynch’s

Mulholland Drive is about Hollywood and

what an aspiring actress has to go through to land a part in

a film.

In retrospect a hint at what else may be at play is revealed

in the final credits, as we see that each actor plays two

characters. But like any good story no time is wasted

setting things up at the outset. In Nina’s dream she sees

herself in the role of the white swan queen. At first alone,

she is soon under the spell of the sorcerer Rothbart,

dressed in black feathers. She tries to flee, but in vain.

Rothbart has stolen her soul. Nina misinterprets the meaning

of her dream, but this is perhaps because she is too close

to Rothbart in her waking life, or soon will be.

Or perhaps we might find an answer in the way Matthew

Libatique lights his film to compress the dynamic range or

that he often photographs Nina a few paces from behind her

as she walks through the corridors of her mind, as if she is

being followed, which she is, is she not? Is it responsible

in some way for that rash that appears on her shoulder? And

what about that she wears white while Nina’s mother, Erica,

and Lily, the company's new dancer and potential challenge

to Nina, wear black. All the more interesting in that Erica

and Lily are in the most direct competition for Nina’s

loyalty. Lily is Nina’s guide across the river into the

Hades where live sex, drugs and rock n roll, while Nina’s

mother demands deference as if Nina is still a young child.

Not least, we certainly can’t help but notice how much of

Aronofsky’s film is shot in reflections, often split or

broken, as she is.

Compressed, broken, split, repressed - Nina moves through

this hour and forty-five minutes like Vicky in that moment

in the Red Shoes ballet when she has fled from the carnival

and wanders in a mist of slowed motion and empty streets

only to find herself alone with fragments of her projected

loneliness and despair. How different Aronofsky’s approach

to a similar subject than was Ron Howard’s for A Beautiful

Mind where that director seemed more interested in tricking

his audience than engaging us in the process of a mental

breakdown.

Whatever might have been the filmmakers’ intention, I rather

enjoy seeing Aronofsky’s movie as a nightmare, one that

begins in what appears to the protagonist as a harmless, if

portentous dream and ends in a delirious, eroticized

metamorphosis. In this view, everything, and I do mean

everything, are projections of Nina’s psyche - of her

desires, repressions, conflicts, urges. She sees these

projections - uh, one moment please - I am suddenly aware of

Di Caprio’s explanation of how the dreamer affects the dream

in Inception - Indeed, Black Swan could easily be seen as a

shared dream. We share this dream with the characters in the

play. Like Thomas, Lily and Erica, we try to invade Nina’s

dream with our own projections. We want to steer her this

way or that and make it all come out in some rational way,

even if it is to explain Nina as psychotic. (Not my favorite

view, by the way)

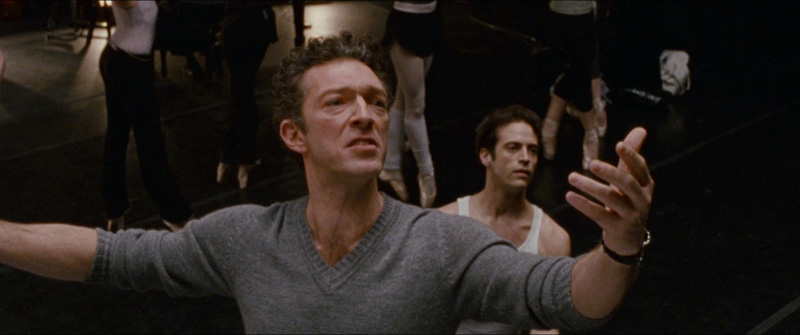

All this psychologizing aside, there is a plot of sorts.

Nina (Natalie Portman) is offered the complex and demanding

dual role of the Black and White Swans in Thomas Leroy’s new

production of “Swan Lake.” While Thomas (Vincent Cassel) is

more confident about Nina’s technique than she is, he is far

less certain that she will be able to tap into the necessary

darkness and let herself go (which he seems to equate with

sex) to play the Black Swan. It is easy to see Thomas as

obsessed with conquest and sex - indeed, this is the view of

his previous “little princess,” Beth Macintyre (Winona

Ryder), who is about to be forcibly retired from both the

stage and his bed. But like most men in power, he is

probably only a narcissist who can’t tell the difference.

But no less obsessed with sex is Nina’s mother (Barbara

Hershey). In her way, Erica is as warped as Piper Laurie in

Brian De Palma’s

Carrie. She has done everything she could

to keep her daughter safe from the seductions of sex -

something she herself was unable to do and which resulted in

the burden of a child (“thanks, mom”) and loss of a career

as a dancer. Erica rationalizes that she protects her

daughter from the big bad world only for the sake of her

career. Like Lermontov, Erica believes she and Nina can’t

have Love and become a great dancer. It doesn’t take a Freud

to see that Nina’s mother resents her daughter, her youth

and beauty, her talent, and the possibility she could indeed

have both - or either one, for that matter.

As I said, poor Nina doesn’t have a chance. Her journey into

paranoia and delusion is inevitable, even if she gets to

wear her shoes and eat them at the same time.

Image:

8/8 NOTE: The below Blu-ray captures were ripped directly from the Blu-ray disc.

Like Nina herself, the image seems on the verge of breaking

down before our eyes, especially if you look at it closely

on a computer display. The focus is sharp enough, but every

effort is made to keep the characters just a bit shadowy and

murky until the final dazzling tableau. It’s a movie that

looks best properly projected, where there is sufficient

space and distance for the eye to fill in the molecular

structure, so to speak.

This is one of those movies where a score for image quality

can be misleading. While far from ingratiating, I do believe

what we see on Fox’s new

Blu-ray corresponds to the

filmmakers’ intentions. Unlike just about every other major

studio’s offerings these days, Black Swan was shot, not on

35 mm film, but mostly with a 16 mm camera with the support

of the Canon 5D Mk II full frame digital camera (I have one

of those for the very reason that it is capable of 1080p

video). The persistent grain apparent throughout the movie,

however, is not so much the result of shooting in these

media (cf: my review of

Pride and Prejudice) but the

use of flared and low light, plus, I suspect, a judicious

amount of post-processing. A bit of noise is inevitable, but

it is hard to tell it from the overall look of the film.

For these reasons, the resultant image may not win any

converts to high definition but it is presented without

blemishes, transfer issue or enhancements - certainly

without noise reduction. By the way, for all its darkness,

there is hardly any true black except in the opening dream.

Interesting: black at the beginning, ending in a fade to

white.

CLICK EACH

BLU-RAY

CAPTURE TO SEE ALL IMAGES IN FULL 1920X1080 RESOLUTION

Audio & Music:

8/9

A good deal of the musical score for Black Swan is derived

from Tchaikovsky’s immortal ballet, “Swan Lake,” the first

of his three masterpieces in the genre (the others being

nothing less than “Sleeping Beauty” and “The Nutcracker.”)

In Nina’s dream that opens the film, we hear his music in

its full orchestration, and it sounds glorious and rich, yet

never overpowers the action “on stage.” And so it is

throughout the movie, whether the music is played by a

rehearsal ensemble featuring Tim Fain’s solo violin work

(whose location on stage is correctly positioned and

balanced as POV changes), or a boombox recording of the

ballet music, a performance orchestra, Clint Mansell’s

subtle cues from the master or his own re-imagining of a

morsel of rehearsal music or music box. Black Swan is alive

with music, always in wonderful balance with dialogue and

effects.

Along with the usual ambient sounds, the movie is alive with

subtle and alarming audio cues from rustling feathers to the

whoosh of a passing subway train to point Nina’s attention

to some shadow that passes behind her or off in some corner.

The sound of creaking shoes on the dance floor and the

preparation of those shoes for the days work are among the

film’s many delights. Bass is relegated almost entirely to

the one club scene where the music is muffled, like Nina’s

consciousness.

As for the dialogue, Black Swan is remarkable for its

naturalistic approach to sound recording. I never had the

feeling that any of the dialogue was looped. In fact, in the

scene where Thomas first address the company as they warm

up, we can make out that his voice changes in quality as he

moves about the floor, facing this way and that, just as it

would if we were standing at the position of the camera.

Extras:

7

In place of an audio commentary, which would have been nice

I think, Fox offers two behind-the-scenes pieces. The first,

titled “Metamorphosis,” is spotlights filmmaker Darren

Aronofsky, Natalie and their crew, working under

extraordinary pressure of time, from the inception of the

dual roles of Black and White Swans, through various aspects

of production to her eventUAL her transformation into the

black swan. It’s an exceedingly detailed informative piece,

sometimes direct, sometimes indirect about the process. In

addition Darren and Natalie we get to hear from DP Matthew

Libatique who talks about lighting and the look of the film

he wanted. Also heard from at some length are Editor Andy

Weisblum, Writer Mark Heyman, Production Designer (I

especially appreciated her comments on blocking in relation

to how the actor naturally moved through her sets),

Prosthetic FX Artist Mike Marino and Visual FX Supervisor

Dan Schrecker. You want to know how they grew all those

feathers, Dan’s your man.

The second group of behind-the-scenes segments concern the

ballet, costume and production design. These are all too

brief to do their subjects justice, and Fox turns the knife

by failing to group them with a Play All. Fox makes the same

mistake regarding the remaining three features: a profile

each for Natalie and Darren (six minutes between them); two

post-production “conversations” between Natalie and her

director about preparing for the role and her dancing

(another six minutes - very EPK); most egregious is the

failure to group the five Fox Movie Channel presentations

(more EPK) focusing on the director and the four principal

actors (totaling 22 minutes, and well worth ignoring.) The

Fox Movie Channel pieces are all done in standard def

1.33:1. All the other features are presented in 1080p.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bottom line:

9

Excepting the mostly routine bonus features and the absence

of a commentary (excepting again the very good fifty-minute

documentary), Black Swan is a must-see, must-heard, and

must-felt movie. And Fox has done all those involved proud. Aronofsky’s

Black Swan is a manifestation of an internal

conflict between irreconcilable forces. The screenplay

maintains the tension in this conflict from the first to the

last frame. This is its gift and its challenge. It may be

that trying to make “sense” of the story is like finding

your way out of Escher’s Ascending/Descending Stairway. My

advice: Let yourself go. Pick yourself up. Embrace the Dark

Side. And start all over again.

Leonard Norwitz

March 31st, 2011

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()