The King and I

Aka: Wangkwa Na

Directed by Lee Young Mook & Son Jae Sung

Written by Yoo Dong-yoon (Ladies of the Palace)

Produced by Kim Jae-hyung (Ladies of the Palace)

Originally aired in Korea on SBS television, from August 27,

2007 to April 1, 2008

Review by Leonard Norwitz

Cast:

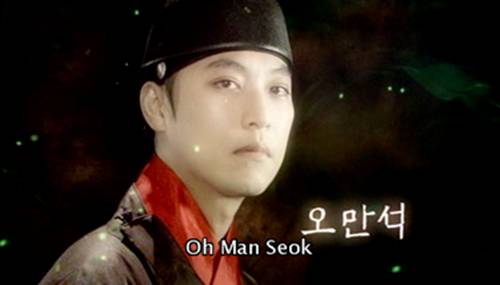

• Oh Man-seok as Kim Chuh-sun (Shin Don)

• Ku Hye-sun as Yoon So-hwa (Ballad of Seo Dong Yo)

• Go Joo-won as King Sungjong (The Bizarre Bunch)

• Jeon Gwang-ryul as Jo Chi-gyum (Jumong)

• Ahn Jae-mo as Jung Han-soo (The Rustic Era)

• Jeon In-hwa as Queen Insoo (Ladies of the Palace)

• Jung Tae-woo as Prince Yunsan (Chihwaeseon)

Studio:

Television: SBS, Korea

DVD Distribution: YA Entertainment (USA)

Video:

Aspect ratio: 1.78:1

Region 1: NTSC

Feature: 480i / anamorphic

Supplements:

Audio:

Korean Dolby Digital 2.0

Subtitles:

Feature: English

Extras: n/a

Extras

29-page Series Guide in pdf (downloadable.)

Presentation

63 episodes, approx. 70 min/episode

Published in 3 box sets

Each box is in book format with 7 discs

Release Dates: October 28, November 25, 2008, and January 6,

2009

Introduction:

If you hate a person, you hate something in him that is part of

yourself. What isn't part of ourselves doesn't disturb us. ~

Hermann Hesse

"Ambition" may be the operant word for this extraordinary

series, since it clearly motivated the writer and producer as

well as several of its principal characters. The King and I,

which runs well over 70 hours, is a fictionalized dramatization

not only of a great many characters and events across the better

part of a century, but the political struggles and cultural

practices of a time now remote. Moreover, the most important

characters in the series are a class of people never before, to

my knowledge, given pride of place in a popular well-funded

television program from any country.

For us Westerners, this 63-part series comes with an unfortunate

title. As you might expect and hoped, the story has nothing to

do with the Rodgers & Hammerstein musical of the same name, nor

is it a similar story placed elsewhere in a different time. To

put us further off the scent, there isn't one king here but

several, two of which we get to know quite well; and there isn't

one "I" but several, again two that command attention in

specific relation to their king.

The kings of our story emanate from Korea’s early Josun Dynasty

throughout roughly the fifteenth century. King Sejo, whom we

get to know largely by frequent reference by those who follow

him, takes power in a coup, an event whose effects rattle on

across three generations. It is Sejo's successors, particularly

Sungjong and Yunsan, on whom the present drama settles. However

the principal focus is not so much on the kings themselves nor

on their policies or legacys, but on the political dynamics and

intrigues between the eunuchs, led by Jo Chi-gyum and Kim

Chuh-sun, and the kings, their royal families and the kings’

ministers.

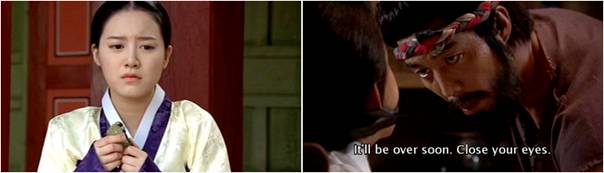

Yes, eunuchs! For it they who are the "I" in the title. And

believe me when I tell you that the story of their induction,

castration and servitude is told explicitly, if not entirely

graphically. This is not a drama for children, though it is

about children, many of whom never grow up – certainly not in

the usual social and political sense. Yet, some of them marry

(sans sex, of course), many acquire wealth (skimming was a

common practice among many who worked in the palace), and some

obtain considerable political influence. Many are filled with

self-loathing, as we might expect; yet try to find some sense of

pride in the work they do and with others of their unique

species. Some, exquisitely, love women, who, for more reasons

than are obvious, are out of reach – and it is this story that

informs the emotional backdrop for The King and I.

DVD REVIEW

Image: 7/6

The score of 7 indicates a relative level of excellence compared

to other standard definition DVDs on a 10-point scale for SD

DVDs. The second score represents a value for the image on a

10-point scale that accommodates both standard and

high-definition video discs – where any score above 7 for an SD

is outstanding, since the large majority of high definition

video discs are 8-10.

Originally broadcast in HD, the image offered by YAE is

excellent: Colors are natural, vivid and well saturated, daytime

or night. The King and I is nothing, if not beautiful to

look at, despite the occasional tendency for Korean dramas to

overexpose the highs, especially in outdoor scenes. There is a

certain confusion of foreground and background when things get

very busy, but this is the fault of the DP, not the transfer.

As usual, the image is non-progressive, but still looks very

good unless paused on your computer where combing and jpg

artifacts are made more apparent. I've seen much worse examples

of combing and edge enhancement from this company.

Audio & Music : 7/5

Like most Korean TV dramas, even those in broadcast in High

Definition, the audio is front-directed stereo. Music, effects

and dialogue are nicely balanced and clear, with generous bass

and clean treble when needed. Unlike the music for Dae Jang

Geum or Jumong, the music here is more varied in mood

and style, which I did not always feel was appropriate for the

scene scored. It is a common practice to simply copy and paste

complete cues for a wide variety of scenes without so much as

re-orchestrating them or altering the tempo. Even though the

audience would have been watching two episodes a week, not five

or six as I did, they could not have helped but notice a certain

degree of careless repetition. Much to my surprise there wasn’t

a single memorable song, nor any that vied for my attention or

affection.

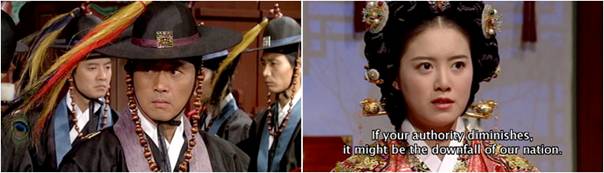

Translation & Subtitles : 5/9

Perhaps the most annoying thing about the subtitles is the

pervasive practice throughout Volume One of indicating not only

the name of the character speaking, but who they will eventually

become (king, queen, eunuch, etc.) So much for suspense!

Instances of misspelling are rare, but there is more than an

occasional misuse of English words that try too hard where a

simpler solution would work better: "overambition" instead of

"ambition" for example. But the more serious problems with the

translation lie elsewhere.

I mentioned earlier that the chain of command is not clear in

this series. There are two problems: The first is that at any

one time it is possible for there to be four different levels of

queen (the king's grandmother, the king's mother, the king's

wife, and the mother of his child). The translation refers to

all of them merely as "queen." Since the screenplay does not

make it clear who has the power of decision, we are never clear

as to the pecking order. For example, there were times when I

had the impression that a consensus needed to be reached before

a proclamation could be issued; at other times I thought that

the king had final authority but would not act without the

blessing of one or both queen mothers simply out of respect. In

other cases, it was impossible to sort out who had the power to

arrest or torture or execute someone or, more important, who

could override such an order. This makes questions of suspense

impossible, since we don’t really know if a particular prisoner,

whose fate we may care about, can be absolved by this or that

official. Koreans would no doubt have enough historical

knowledge about these times and persons that they do not require

the level of clarity non-Korean do. All the more reason for the

translation to be helpful.

Second, while it was evident that "ministers," "officials,"

"royals" and "eunuchs" all had their place and spheres of

influence, it was not clear what that was or how it worked.

While I did not expect that the screenplay or translation would

place itself on pause and explain to the audience: "Now in 1476,

the Korean system worked thus . . ." I did expect that such

matters or the roles of the several queens would be addressed in

the pdf booklet. Except for the in-depth discussion about the

history and roles of the eunuchs, we learn very little about the

way the government actually works.

There are other problems with the translation (which, by the

way, was not created by YA-Entertainment staff, even though the

series is distributed in North America by them.) The first is

the frequent and entirely inappropriate use of western

colloquialisms. The action in the palace gets the worst of it.

For example, a person might be asking of an authority figure: "I

know that so-an-so just tried to poison the queen but I'd like

you to let is slide." Not only is the expression "let it slide"

out of time, but it makes light of the situation, don’t you

think. My favorite, and laugh out loud example of the misuse of

western expressions occurs numerous times about midway into the

series when the king is engaged in a secret affair with a

married woman in the village just outside the palace. This is

referred to by just about everyone as "dating."

Another problem is more pervasive: the translation, especially

as regards the action in the palace, makes everyone appear less

important and more impotent than they are, even the non-eunuchs

– though they are the most frequent abusers. People make

threats and promises they don't keep, for it they did, the

series would come to an end much sooner than it does. For

example, when it becomes clear that so-and-so is involved in a

plot to frame the queen for what would be a capital offense, the

good guy says to the bad guy: "I'll forgive you this time, but

if you do this again, you'll pay," or "I'll never forgive you,"

or "I'll kill you." But none of these things ever happen

(except when Queen Insoo says it – she rarely misses an

opportunity to torture or send someone away from the palace in

disgrace). This not only weakens the offended person and

strengthens the offender, but brings attention to a serious

weakness in the screenplay: that hardly anyone follows through

on their promises, so we start to lose interest.

Operations & Box Design : 8/9

As we've been seeing more frequently from YAE, the names of the

stars appear in English over the episode's credits as they and

their characters are introduced. A nice trend. The menu is

uncomplicated, again in English (as is always the case with YAE),

with animated thumbnails for chapters.

The King and I

is packaged in three hefty volumes of seven easily removable

discs, one disc per page. What is unusual is the thickness of

each page: about 6 mm. This makes for a heavier, more luxurious

box than anything YAE has previously offered, or most anyone

else for that matter.

Extras : 7

The Extra Features consist entirely of a nicely produced

29-page Series Reference Guide as a downloadable pdf. This

makes it harder to misplace, but less handy if you want to thumb

through it while watching your program. Of course you can

always print it out. For what it does cover – a look at ancient

Josun history, its kings and the cultural value of the eunuchs,

it is an excellent resource – as far as it goes. It also

briefly sketches out a half dozen of its major characters.

However there are questions that come up for Westerners that are

not addressed in either the translation or the booklet: for

example the political lines of authority and job descriptions,

so to speak, of the ministers and officials and the

simultaneously serving queens. Nor do we ever get to find out

what exactly are the "3 virtues and 3 flaws" that make Chuh-sun

the "perfect eunuch."

Recommendation: 6

At last, a Korean drama that doesn't center on food. The King

and I is a historical drama whose main characters are

eunuchs and the political, ethical and marital crises they

face. The series is much longer than it needs to be and doesn't

take advantage of the time it allots itself. It is marred by

repetitious situations and cliffhangers and a clumsy translation

that starts off well enough but gets lazier as it goes along.

The series is photographed in luscious color, with high

production values, especially as concerns the extravagant and

varied costumes. It is filled with affecting performances from

everyone except one of the leads. Unlike most Korean dramas

I’ve seen, the score is not memorable, with nary a single song

to stir the heart. Recommended especially for a Korean speaking

audience or English-speaking if they can be forgiving of basic

translation problems.

DRAMA SERIES REVIEW

The Series : 7 (of 10)

Story:

The political drama is always front and center, especially once

the eunuchs we have been following since childhood take their

places in the palace pecking order. The political conflict for

them is the tension between loyalty to their oath – to serve and

protect the king – on the one hand, and loyalty to a patriot's

sense of right, wrong, justice and country on the other. A

eunuch who has risen through the ranks is in a sensitive and

influential position in relation to the king, and if such a king

were to step over a line, from simple courtesy to despotism, a

eunuch finds himself in a difficult situation, for they are

forbidden to be involved in politics – a rule that cries out to

be broken. Such crises of loyalty compel them to make ethical

compromises that they must forever rationalize – sooner or later

to their peril.

As in any good drama, the "bad" guys are far more interesting

than the "good" guys. I think it's no exaggeration to say that

the balance is laughable at times. The bad guys, for example,

conspire in whispers and have spies everywhere. The good guys,

and anyone else who is vulnerable, speak publicly and have no

spies. They never look over their shoulder to see if anyone is

following them, for if they did, the series would rapidly come

to an end. This is a strategy common to Korean dramas, however

odd it will seem to western audiences.

And if you think that the western judicial system is too lenient

on criminals, wait until you get eyeful of how it once was: In

those days, all one had to do was present circumstantial

evidence to the right person to have the accused tortured -

guilty or not - until they confessed – a confession whose only

relief is a quicker execution. No one would dare speak for the

accused since guilt was assumed, and defense would imply

complicity. Worse still, if competing hypotheses were advanced

to explain how the accused committed the crime, the one that

supported the accusation was always favored, as was the rank of

the accuser, leaving the accused to prove a negative: How for

instance does someone prove that they did NOT poison so-and-so

without finding the culprit and securing a confession, and how

could they do that while being tortured or imprisoned. In those

days, the concubines were always vying for power against each

other and against whatever wife of the king is currently on the

throne. Their object: deposition. It makes for a delicious

concoction of exquisitely executed framings, exorbitant

extortions and ready-to-eat poisons.

It doesn’t help that the writer for this series has made

well-meaning investigators unbelievably stupid, often ignoring

obvious leads. Chuh-sun, for example, has the annoying habit of

asking someone he suspects (his intuitions are generally

correct) if they know anything about the crime, fully convinced

that he would get an honest answer simply because HE would give

an honest answer. Though the "suspect" may look as guilty as

hell, after 60 episodes Chuh-sun never acquires the wisdom of a

seven year old in such matters – yet he feels he is the right

person to head up a secret investigation simply because no one

has more loyalty to the accused than he. In such matters, the

man is an idiot.

Which leads me to say a few words about the king – or one of the

kings: Sungjong. We should call him “King of Rationalizers!”

The way he excuses himself for carrying on a secret affair with

a married woman, all the while claiming to his wife, who knows

about the affair, that he is loyal to her and that she (his wife

and queen) is, always has been and always will be the “love of

his life” makes you want to take this guy around back and beat

the crap out of him. If this weren’t enough, he is told by his

trusted friends who know about the affair that once the

ministers find out about it they will use the information to

blackmail him, which would further weaken his authority. He

would become a king in name only. And if this still weren’t

enough, if he were to continue to continue this affair, he is

told that sooner or later both she and his queen would find

themselves in mortal peril. So, with his own authority, the

authority of the royal family and the lives of the two women he

claims he loves in jeopardy, he has the chutzpah to indulge

himself with sighs of remorse as his world falls apart. And

then, to top it all off, he decrees that the matter is not be

discussed or investigated for 100 years, leaving his son in

ignorance and his teachers helpless to guide him. Talk about

political inbreading!

Performances:

A few words about the actors in this drama. With one important

exception, all the roles are well cast and characterized, save

that some of the younger actors (especially Go Joo-won before he

adopts a small beard) look too modern. I mentioned earlier that

Chuh-sun was good at keeping secrets. The actor who plays him,

Oh Man-seok, makes certain that the audience knows as little as

possible about the inner struggles he must certainly entertain,

for he is the most uncharismatic Korean actor I've come across.

Oh makes it clear what charisma is about since he affects none,

except that he has an unfortunate half-smile that makes his

character look like a simpleton. It is not until the final

episodes that Chuh-sun finally admits to himself the Truth and

pays the price – or becomes a hero, depending on how you see

it. But until then, he does not let on. I suspect that the

actor has been directed to remain stone-faced, but whenever he

is on screen I hold my breath, as he seems to. (My Korean

sources tell me that my feeling about this performance is not

typical of Koreans.)

Fortunately there are many other characters, great and small, to

distract us from Oh's mind-numbing performance. At the head of

this class is Jeon In-hwa, who plays Queen Insoo, the real power

behind the throne – a woman who seeks control and fears the loss

of it like alternating current. Jeon’s performance allows us to

feel the strength of Insoo’s conviction as well as the

tenuousness of her hold on circumstances within and without the

palace.

Then there’s Jun Hye Bin who plays the quietly scheming Sul-young,

a woman who could wither you with a glance. And there are two

men who remain faithful to their cause forever, and we admire

them for it: Gae Do Chi, the castrator, played with great

subtly of feeling by Ahn Kil Kang, a man racked with the guilt

of stealing future generations from children who are hardly old

enough to give informed consent. And Han Jung Soo as Do Geum

Pyo, Chi-gyum’s formidable bodyguard: skillful, watchful and

silently devoted. Speaking of formidable, age is no object to

Shin Goo, nor his character, Noh Nae Si, a hoarding, spiteful

man, despite and because he requires the help of a young woman

just to stand and move about. On the other hand he has perhaps

the clearest notion of what's always at stake, as he advises

Chi-Gyum who is considering whether to join the coup, "You will

become a hero or a traitor. It's a very thin line. " It's a

question asked repeatedly throughout the series. Noh adds,

"Though dynasties may change and kings will come and go, our

testicles will never grow back."

There are many interesting characters and fine performances, but

I shall single out one more: Yoon Yoo Sun as Wol Hwa. We’ve

seen her before as the resolute queen in the contemporary young

adult comedy/romance “Palace”, but here she is most

touching as a self-effacing, childless shaman who finds an

infant child in the forest and raises him as her own. She is

chronically frightened that the boy will discover she is not his

mother and the identity of his real parents are – not that she

knows. When he decides to become a eunuch and when it becomes

clear to her who his mother really is, a woman she has the most

tender regard for, she still refuses to reveal the truth to

him. The irony is that his birth mother is actually his nurse,

but because of her amnesia does not know recognize her own

child. There is enough material in this triad alone for an

entire series, and Yoon Yoo Sun does an admirable job of

gradually withering away before our eyes as she watches

Chuh-sun’s fate unfold.

Characters

Instead of continuing to summarize pieces of this complex plot,

I thought it might be more interesting to describe the essential

dilemma or ambition of each of the important characters:

Kim Chuh-sun:

From his youth he had borne a crush for So-hwa whose affections

lie instead with another childhood friend, a boy who eventually

becomes King Sungjong. Chuh-sun is a man who keeps secrets so

well he even keeps them from himself, and refuses to admit his

true feelings. He becomes a eunuch in order to serve and protect

So-hwa, who has since been selected as a royal concubine. He is

helped in his endeavors by Palace Head Eunuch, Jo Chi-gyum, who

adopts Chuh-sun as his son. Chuh-sun's dilemma is that he

cannot reconcile the needs of state with the uncompromising

ethical system of rules he has chosen to live by, doubtless in

order to keep his longing for So-hwa suppressed. He serves two

masters: the heart and the head, and though he suffers from the

weight of his dilemma, he is painfully impotent to fully act on

behalf of either.

Yoon So-hwa:

So-hwa's father has been, like so many others in this story,

framed for crimes he did not commit, and is eventually disposed

of, leaving his family disgraced. But when the man she loves

becomes king, he is determined to bring her into the palace, if

only as a concubine, regardless of the target of treachery she

will necessarily become.

King Sungjong:

When Sungjong bring So-hwa into the palace against the

objections of the royal family and just about everyone else, it

represents one of the few times this spineless, mama's boy gets

his way. Unfortunately he is a weak king who never gets the

hang of the chain of command any more than we do, resulting in

considerable and tragic outcomes for those he loves.

Jo Chi-gyum:

It is with this eunuch that The King and I gets under

way, long before Songjong is enthroned. Jo betrays his friend,

who has attempted to lead a coup against the king. His friend's

wife, for whom Jo always had more than a passing interest,

escapes with her infant child whom she hides in the mountains

before she falls off a cliff and becomes amnesiac for the next

couple of decades. When Jo, already married, finds her, he

cares for her indirectly, and tries to locate her missing son

(this much she remembers). The irony is that this son is none

other than Chuh-sun who was found by a shaman and raised in the

shadow of a school for eunuchs.

Jung Han-soo:

One of the more interesting figures in this drama, Han-soo is

not of low birth, and is sold to the eunuch school to help keep

his family from being thrown into the street. He is a boy of

rare intelligence, who grows up with a passionate jealousy of

the interest paid to another boy by people in power and, like

Lex Luthor, applies his skills to anarchistic ends. His

overwhelming interest is in the accumulation of power to wield

against those he feels were responsible for placing his family

in such straits as would necessitate his becoming a eunuch.

Han-soo is a vivid portrait of self-hatred and utterly

unconscious of it, except in moments of intense passion.

Queen Insoo:

The woman we love to hate. Insoo is Sungjong's mother and

guides her son-king with an iron fist, even after he is old

enough to no longer require his mother and grandmother as

regents. Her prejudices fail to allow her see the truth, but

she is always guided by her keen political understanding. She,

more than anyone, even the king, understands that the king can

do nothing without the ministers; and if they want someone

removed from the palace or arrested, or tortured, or even

deposed, their wish must be her judgment.

Lord Noh:

Jo Chi-Gyum's adoptive father, and the most powerful of the

eunuchs, now retired, but always at work in the background to

ensure his sphere of influence. He is not averse to a little

extortion or murder to achieve his ends.

Sul-young:

One of the most beautiful vipers ever to grace the soap box, Jun

Hye Bin plays Seol-young, who spends most of her hours in

silence, pouring tea and helping the elderly Lord Noh move from

this posture to that. She uses her beauty and not

inconsiderable, persuasive intellect to affect some of the more

spectacular murders in the palace.

Eulwoodong:

The Other Woman: Beautiful and talented. Resentful and tragic.

One of the few completely honest figures in this drama, not that

it gets her anything but our sympathies.

King Yunsan:

Truly a despot for the ages, though he doesn’t start out that

way. Rather, he is a victim of never having been told the truth

of the circumstances regarding his mother’s death. And so when

it finally emerges, as it must, he is totally unprepared, and

the self-fulfilling prophesy of reprisals that the ministers

feared all along happens, big time.

Leonard Norwitz

June 6th, 2009

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()