Following upon his first Ghost in the Shell animé feature film, as if two entire TV series did not exist between them, Mamoru Oshii picks up after Major Kusanagi retires herself (sort of like Dr. Who, I always thought). Batou, her bionic partner in the special police unit known as Section 9 that investigates cybercrime, together with Togusa, one of the younger, mostly human, cops (with a family, no less), is now looking into the murders of owners of robot-dolls by the dolls themselves who, in turn, self-destruct.

I've seen the movie three times now, twice on SD-DVD and just now on Blu-ray. I can't say that I can follow the convolutions of the plot exactly – not, I suspect, because it is opaque or confusing – though there are those aspects, but because I get utterly caught up in the astonishing visuals, the music and the soundtrack. From its first frames, we are aware that Ishii has taken the art form in a new direction – as did Wagner between the second and third acts of Siegfried. Purists will have complained about so much CG in what, after all, had been a fairly static presentation, with time-honored, if parochial, conventions: Animé should be thought of as a comic book in motion, rather than a stand-in for real people and places. This is why jaws go up and down, but lips don't sync, and why backgrounds are relatively immobile, and why lateral motion is so staggered, suggesting movement from graphic pane to graphic pane.

Over the few years since the movie's release I've read the occasional review, hoping to gain some further insight into its context. I can only say that there are some disappointed critics out there. One of their complaints was how much intellectualizing and philosophizing there was in this movie – as if that isn't what characterizes animé more than any other cinematic medium – and that the sheer volume of dialog threatened to overwhelm the story. But I suspect that many are simply not up to the task of sifting through the layer upon layer of interdependent literary, philosophical, cultural and political references. Not that that I'm that much more astute – I'm just reluctant to kill the messenger just because I don't get it. I was fully prepared to write a review that would say just about that much and throw in some nice comments about the picture and sound and, hopefully, not embarrass myself. But then . . .

Last week I had a few friends over to choose whatever BD they wanted to watch and, to my surprise, they picked Innocence. True, they were enticed by the brief segment I played (you can probably guess which), but what really got their juices going was the screenplay (in translation, no less) and how the visuals supported it. So, without getting into the plot, here's their summary (with many, many thanks to Lee Chen & Michael Barry). There's a feast to chew on here, so sit back and make yourself comfortable:

The film, Innocence, expresses an acute cultural anxiety through its use of simulacra, namely dolls, ghosts, puppets, cyborgs and prosthetically modified humans. It draws heavily on the tradition of early twentieth-century literature that invokes anthropomorphized objects (especially those with human form) to make social and metaphysical commentaries and criticisms. The primary references here are E. T. A. Hoffman’s short story Der Sandmann (the inspiration for the ballet, Coppélia) and Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies. Both works attempt to position the human between the material/mechanical world of puppets and the immaterial/spiritual world of angels. Puppets and angels, unlike humans, are inherently innocent, but both are “dead,” as we all will one day be. Therefore, the puppet and angel stand, potentially, as past and future selves. Rilke’s Fourth Elegy makes this explicit.

One cannot view Innocence thinking that the imagery in this poem was implicitly present throughout. The Fourth Elegy, in turn, was inspired by a Kleist essay Puppet Theater. Also, Rilke wrote an intriguing essay entitled On Toys which can be found in the book Rodin and Other Prose Pieces.

Interestingly, the early 20th century anxiety surrounds the “mechanization” of the world – hardware approximating human body. In Innocence, the anxiety surrounds the “computerization” of the world – software approximating the human soul. Unlike Blade Runner, where the main questions seem to be “How long will I live?” and “Does she love me?” (both very American concerns), Innocence presents the Japanese concern of “Do I still have a soul?”

Also note that, in Innocence, the photo book that has the picture of the little girl in it was a title by Hans Bellmer. Given that the dolls depicted in the movie were virtual copies of Bellmer’s, I can see why the filmmakers felt the need to reference him directly.

HERE

As we can see, crises of identity invariably create artistically-rendered sexual mutilations of the body to represent the corruption/deformation of the “soul.” This arises from the fact that, as William Gass wrote, “Consciousness is nothing. No thing. A gunnysack full of Polish teeth occupy for space in this world than all the agony of their extraction.”

LC/lmn

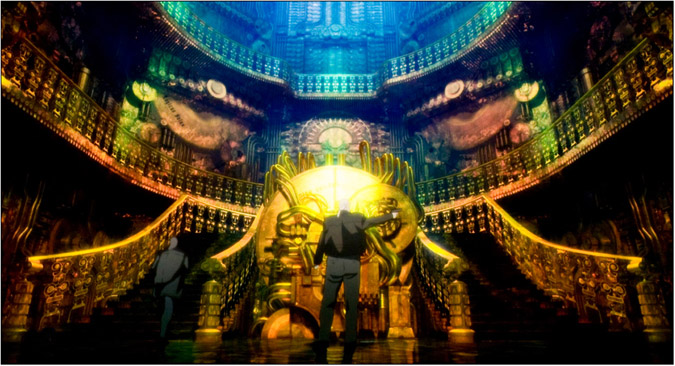

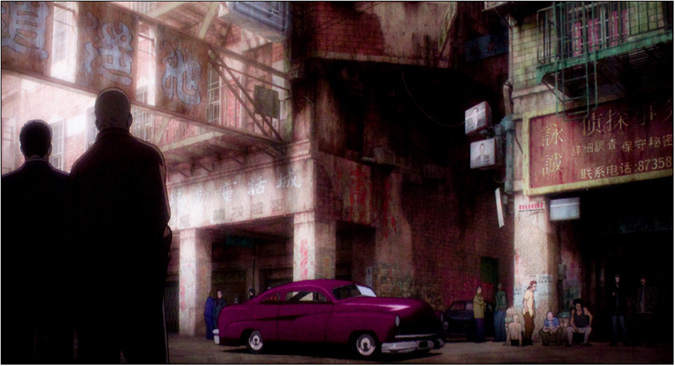

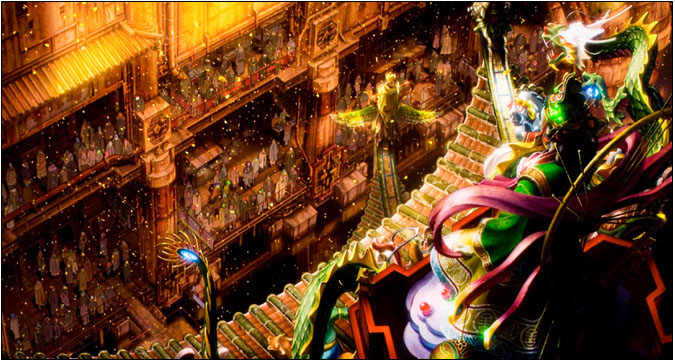

Innocence portrays a Japan that has ceased to be the maker of things. Material production has become China’s province, as represented in the lavish, brilliantly colored Chinese barge imagery that dwarfs the grey-garbed Japanese interlopers. The question for the Japanese then is less “Do I still have a soul?” than “Am I real?” Although Japanese animé is one of the more successful Japanese exports at present - their bleak vision reflects the depressed Japanese business market. The absence of Japanese automobiles in the future is also telling. The ersatz “nostalgia” for foreign cars bespeaks a rejection of the mundane – preferring instead the hyper-reality of “noir.”

MB/lmn