|

Even though I don’t have much of a head for science, and even though

I agree with the field’s chief literary critic, Damon Knight, that

“we have no negative knowledge” (meaning that we aren’t yet in a

position to identify time travel as either science or non-science),

I’d still maintain that the differences between science fiction and

fantasy are important. (For Damon Knight’s criticism, see his superb

though sadly long out-of-print collection

In

Search of Wonder.) Important enough, in any case, to make a list of favorite neglected SF movies distinct and separate from a list of

neglected fantasy movies. So consider the following selection the

first half of a two-part series.

French people tend to conflate SF and fantasy a little more readily

than others do into a looser category known as fantastique which

also manages to encompass Surrealism, some forms of satire and

horror, comic strips, comic books, and graphic novels, among other

things. But for the purposes of this particular exercise, credible

extrapolations or fictions that at least pretend to have some

relation to science—-by which I mean

Charlie and the Chocolate

Factory (admittedly a borderline case),

The Nutty Professor, and

The

Incredible Shrinking Man, but not

Pandora and the Flying Dutchman,

The Tiger of Eschnapur, or

Eyes Wide Shut—-qualify as science

fiction. I’m also including social satires like Privilege (or

Alphaville--the supreme example, though not exactly neglected) that

toss various pop references into the mix, but not outright political

cartoons like

Dr. Strangelove and William Klein’s

Mr. Freedom. I’ve

also opted for relegating horror in most of its guises to fantasy,

with the sole exception of

The Nutty Professor. I realize there’s

something highly idiosyncratic and arbitrary about all this, but I

should stress that I’m proposing offbeat selections here, not

necessarily nominations for official classics.

Two more areas of exclusion: I have a somewhat unfashionable

preference for good movies over bad ones, despite the fact that more

fan magazines nowadays seem devoted to the latter than to the

former. This doesn’t mean I’m immune to the charms of camp; if I had

to choose between any Flash Gordon serial and any Star Wars movie,

the serial would win hands down. But since I also tend to regard

Sergei Eisenstein’s

Ivan the Terrible as the greatest

Flash Gordon

serial ever made, I’m happier when it’s the good stuff that’s going

over the top. And for similar reasons, I’ve also avoided movies with

awesome individual shots or sets or sequences, such as Just Imagine

(1930) and

This Island Earth (1954), if the rest of what one sees

doesn’t live up to them. (If practically all the shots are awesome,

as is the case with

Zardoz, I’m more prone to put up with campy

content.) One final point: the first two and last two selections on

my list are all films I regard as major, and the same goes for

The Nutty Professor; the remaining five are exciting, but not on the

same level.

|

1)

Paris qui dort/The Crazy Ray

(René Clair, 1925). Clair’s second film

after his 1924 Entr’acte (a dada effort designed as part of a

ballet) is far from being the first SF movie. (At the very least,

it’s preceded by Abel Gance’s six-minute 1915 La Folie de Docteur

Tube and Yakov Protazanov’s far more elaborate 1924 Soviet

production

Aelita, with futurist sets and a few scenes set on Mars.)

But this poetic comedy is special in the way it ties its SF premise

to what movies can do, such as freeze or speed up the action.

The Eiffel Tower’s night watchman awakes one morning to discover

that all of Paris has frozen in its tracks, and an airplane’s pilot

and passengers land and make the same discovery—-that everything

came to a standstill at 3:25 am, including the clocks. The hero and

the others then go on a drunken spree that lasts four days, enjoying

their freedom to break into houses and go into nightclubs without

paying. Eventually, after becoming bored, they discover that a

professor, the uncle of one of the passengers, immobilized the city

with a crazy ray, at which point they get him to start things up

again. |

A certain amount of restopping, restarting, and speeding up the life

of Paris follows.

Originally about an hour long, this was

re-edited by Clair into a brisk 35 minutes in the 1950s, and this is

the version available as an extra on the Criterion DVD of Clair’s

first sound feature, the engaging Under the Roofs of Paris (1930),

which features the same lead actor, Albert Préjean.

|

2)

Metropolis

(1927). Ever since H.G. Wells called Fritz Lang’s

gigantic UFA superproduction silly, others have tended to follow

suit, including Lang himself. The movie’s final scene unquestionably

qualifies as over the top, and the same could undoubtedly be said of

certain other parts of the film as well. But however hokey this

pseudo-Marxist vision of a future city might be, the Freudian

subtexts of the original version—-before Paramount Pictures, the

American distributor, started editing out entire subplots and

obscuring some portions that remained--are surprisingly dense and

sophisticated. Not all of the original film survives today, but the

superb restoration overseen by Martin Koerber, using stills and

intertitles to represent the missing pieces, finally makes the full

design of Lang and his wife and cowriter Thea von Harbou clear, and

it’s a revelation. (See Tom Gunning’s 2000 book

The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and

Modernity for an intricate unpacking of the film

as an allegory and how this aspect has tended to taint

most critical appraisals of it; |

|

Gunning’s treatment of the clashes

between Gothic and modern imagery and the way they tend to displace

the conflict between classes in the film is especially insightful.)

In fact, I’d argue that Metropolis, set in the 21st century, looks

less dated and seems more relevant to 2006 than

2001: A Space

Odyssey—-an irrefutable classic in other respects that I’ve omitted

from this list only because, like such 50s classics as

The Day the

Earth Stood Still,

Forbidden Planet, the original

Invasion of the

Body Snatchers, and

The

Incredible Shrinking Man, it qualifies today

as neither neglected nor underrated. (I suppose it could be argued

that

Metropolis isn’t neglected either, but I would counter that the Koerber restoration is.) No less tellingly, the robot Maria in

Lang’s masterpiece anticipates Gigolo Joe in

A.I. (see below) in

many significant aspects.

|

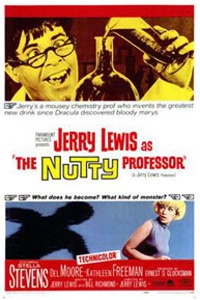

3)

The Nutty Professor

(1963). Yes, I know, this is almost never

classified as SF. (Neither, for that matter, is the no less

deserving 1935 James Whale masterpiece,

Bride of Frankenstein, whose

own literary source, by Mary Shelley, all but invented SF as a

literary genre.) But part of the point of this list is to stretch

the categories a little, and Jerry Lewis’s best feature, a highly

personal take on the “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” story, is surely no

further removed from science than the space operas of George Lucas.

(Furthermore, the brightly color-coded test tubes of Professor

Julius Kelp are surely just as speculative as the Star Wars

costumes.)

It’s been argued that Lewis’s Mr. Hyde, Buddy Love, is a

reincarnation of his former partner Dean Martin, but

this is a misconception that takes some of the edge off

Lewis’s achievement. While Kelp was based on his

observation of a real-life model (according to Lewis,

someone he met on a train), Buddy Love is nothing more

or less than a caustic self-portrait of everything Lewis

finds most odious about himself.

|

And, as with Orson Welles, it

can be argued that his auto-critiques are far more devastating than

anything that could be said by his detractors. Even more striking is

this film’s pessimistic and sorrowful conclusion—-that everyone,

including Stella Stevens’ character and us, prefers the greasy and

aggressive braggadocio of Love to the gentle and klutzy fumblings of

Kelp.

|

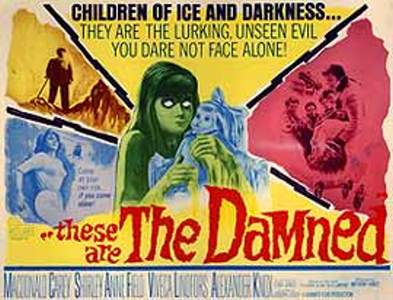

4)

The Damned

(1963). Released the same year as Lewis’s masterpiece but

made two years earlier—-and retitled These Are the Damned by its

U.S. distributor—-Joseph Losey’s only SF film, strikingly shot in

black and white ‘Scope, is no less bleak in its estimation of

mankind, either in the present or the foreseeable future.

Unavailable today on DVD apart from an ugly and pirated pan-and-scan

version, this enduring and topical curiosity deserves much wider

circulation.

Adapted by Jamaican writer Evan Jones from H.L. Lawrence’s novel

The

Children of Light, it was the first of four kinky features that

Jones wrote for Losey (to be swiftly followed by

Eva,

King &

Country, and

Modesty Blaise), and its strangely |

|

twisted action-thriller plot gradually registers as a ringing

indictment of nothing less than western civilization.

Starting off with a

hectoring rock song called “Black Leather,” it follows the

adventures of an American tourist (Macdonald Carey) in an English

coastal town who gets beaten by Teddy Boys after the gang leader

(Oliver Reed) uses his own sexy sister (Sally Ann Field) as bait.

She subsequently flees from her incestuously hung-up sibling, hiding

out with the American on his boat and in the seaside studio of a

local sculptor (Viveca Lindfors). As the brother continues his

pursuit, they stumble into an underground bunker housing radioactive

children who are raised and monitored via closed-circuit TV--the

victims of a military experiment conducted by the sculptor’s lover

(Alexander Knox) that’s designed to enable the kids to survive a

nuclear holocaust. Apart from the bland American, everyone’s a wild

card in this bitter parable. (Lindfors’ sympathetic character is

especially interesting.)

|

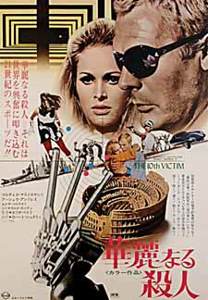

5)

The 10th Victim

(1965). Elio Petri’s cynical, glitzy, violent and

poker-faced pop Italian comedy, set in the 21st century, squares off

Marcello Mastroianni in a blond wig with Ursula Andress in a

protracted erotic skirmish.

The Robert Sheckley story it derives

from, “The Seventh Victim”—-which I presume was renamed to avoid

confusion with Val

Lewton’s 1943 masterpiece chiller—-is

similarly set in a future in which war has been

abolished, and international government-sponsored

“hunts” with extensive media coverage are designed to

work off human aggression. Each participant signs up for

ten hunts—-half as hunter, half as potential victim—-and

whoever succeeds and survives all ten becomes the member

of a prestigious club. A male hunter on his seventh hunt falls in love with his

female prey on her tenth outing, and he winds up doomed by his

infatuation. The movie reverses this setup—-Andress is the hunter on

her tenth round; Mastroianni is the hunted on his seventh—-and the

tone’s far too facetious to allow for love. |

After a prologue in

which Andress performs her ninth kill by spraying bullets from her

brassiere in a joint called the Masoch Club, the scene shifts from

New York (where the original story was set) to Rome, where she and a

seemingly bored Mastroianni stage their seductive confrontations in

settings charged with satiric, high-tech details. According to

critic Manny Farber, “in certain nonplot scene” the movie “comes

close to the perfumed eroticism that is always promised in painting

by Rothko or Jasper Johns but never delivered.” In other words, you

might say it’s too stylish for words.

|

6)

Privilege

(1967). Peter Watkins is the supreme master and very

nearly the inventor of the pseudo-documentary, which he uses as an

unorthodox way of recounting history or projecting contemporary

trends into the near-future. This dystopian Universal release is

about the fascist takeover of Great Britain, with a duped and

manipulated messianic rock singer (Paul Jones, lead singer of

Manfred Mann in his first film role) used as a political as well as

marketing tool. This comes from Watkins’ greatest period to date,

which also produced

Culloden (1964) and

The War Game (1965). The

latter two films have recently been issued on DVD, and so have the

subsequently made

The Gladiators (1969) and

Punishment Park

(1971)—-both of which, along with

The War Game, also qualify as SF,

so a long-overdue rediscovery of early Watkins is already in

progress. I therefore assume that the only thing preventing us so

far from having this ferocious satire on DVD is the fact that,

unlike the others, it was released by a major Hollywood studio—-and

didn’t fare well at the boxoffice in 1967, when the public wasn’t

ready for it Let’s hope that some enlightened Universal executive

realizes that it’s hour has finally come and does something about

it. |

|

|

7)

Je t’aime, je t’aime

(1968). Alain Resnais’ time-travel feature—-a

major influence and inspiration on

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless

Mind, but unfortunately the only Resnais feature apart from the

exquisite Providence that’s still unavailable on DVD—-confounds the

most common American criticism of him, virtually copyrighted by

Pauline Kael, that his films are cold, cerebral technical exercises.

In fact, Kael had it backwards. This poignant story about a failed

suicide who’s sent into his past as a scientific experiment that

goes awry—-so that he’s hurtled through an achronological mosaic of

fragments from his life, sometimes getting stuck in repetitive,

arbitrary moments, while taking us along with him on the bumpy

ride—-is full of intensely passionate and melancholy feelings, as

the film’s very title (“I Love You, I Love You”) suggests. But when

it comes to the film dealing with the scientific and technical side

of time travel, it’s awkward and unconvincing. |

One reason for this discrepancy can be traced back to this film’s

relation to fantastique. The screenwriter, Jacques Sternberg, is a

Surrealist, and Resnais got him to write hundreds of pages of

“automatic writing” that the director then spent years editing into

a script, depending on his own unconscious mind and instincts as

well as Sternberg’s to furnish the story’s strong emotional content,

and meanwhile treated the scientific basis for time travel as a kind

of whimsical joke.

|

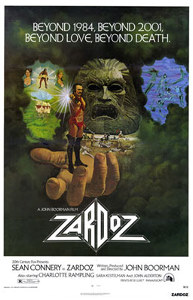

8)

Zardoz

(1974). Speaking of Kael, she made a lot of sport out of

ridiculing John Boorman’s ambitious SF epic

when it came out, overlooking its own traces of irony (such as its

references to

The Wizard of Oz) to concentrate on its high-flown

intellectual pretensions. I suppose she had a point, but considering

how beautifully and masterfully Boorman manages to fill all his

CinemaScope frames, it’s a point that can be harped on only at the

expense of overlooking that this film’s brilliance and its absurdity

are really opposite sides of the same coin. Theoretically, one could

make the same sort of criticism of the delirious crazy-house mirror

shootout at the end of Orson Welles’

The Lady from Shanghai—-a

sequence Boorman evokes in

Zardoz. But one would miss out on all the

fun in the process. In the year 2293, most of the world, now

polluted

and infertile, is ruled by a flying stone godhead with a voice named

Zardoz, secretly controlled by a wizard. Zed (Sean Connery), one of

the warriors carried around by

Zardoz,

kills the wizard, lands on earth, and stumbles upon the

Vortex, a 300-year-old elite commune of immortals

preserving the world’s knowledge, which proceeds to

study this primitive for research with the intention of

killing him afterwards, until he stages a rebellion.

|

|

This is a very simplified

synopsis of an extremely complicated plot that also involves

Charlotte Rampling as an immortal. Perhaps a better summary would be

to compare Zardoz to Boorman’s best film--his 1967

Point Blank--and

note that both films could be called Tarzan versus IBM, Godard’s

original title for

Alphaville (with Lee Marvin taking over the

Tarzan role in the earlier film). Both chart the fool’s progress of

primitive heroes working their way up mysterious pyramids of power,

only to discover an ineffectual clown like

the Wizard of Oz

at the

top. This isn’t the whole of

Zardoz, to be sure, but at least it

suggests that Boorman spices his own deep-dish musings with an

occasional grain of salt.

|

9)

Stalker

(1979). There are few such ironies in Andrei Tarkovsky’s

free and very great adaptation of Arkady and Boris Sturgatsky’s

dystopian novel

Roadside Picnic. But one that does crop up

unexpectedly figures as one of the only genuine, laugh-out-loud gags

in all of Tarkovsky’s work. After a scientist and writer accompany a

guide, the title character, through the better part of this

slow-moving, 152-minute epic, traipsing endlessly through a

poisonous and dangerous wasteland to arrive at the Zone--a

mysterious room that is said to hold the power to grant their

deepest wishes—-they arrive at this decrepit, abandoned location

only to hear a phone ringing inside. As an artist, Tarkovsky himself

hated the very notion of science fiction; according to

him, his previous and only other foray into the genre,

Solaris (1972), failed because it was too much

like SF. (On other occasions, he objected even to the

notion of movie genres, arguing that film itself was

already a genre in its own right.) I don’t believe he

objected to

Stalker on the same grounds, but it must be

admitted that his trancelike and highly spiritual

narrative is so adept at creating its own rules of form,

narrative, and meaning, that SF serves more as a gateway

into its manifold riches than as a final destination. |

To ‘fess up, the first time I saw this film, my dashed expectations

about SF in general and the Zone in particular made me livid for

most of the running time, and I stuck around more out of morbid

curiosity than for any other reason. But by the end I started to

realize that my dashed expectations were the precise subject of the

film, and what Tarkovsky had to teach me about this subject is still

reverberating.

|

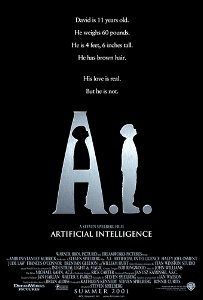

10)

A.I. Artificial Intelligence

(2001). Unlike most of my friends and

colleagues, I’ve treasured this bittersweet SF remake of

Pinocchio—-the tragic yet happy tale of a robot who winds up

expressing the final breath of mankind--since the first time I saw

it. It held me spellbound from first frame to last, and frankly,

through all my subsequent viewings, it continues to move and speak

to me more than any feature I’ve seen since. So those who say that

it should have ended a few scenes earlier or that the bits with

Gigolo Joe (Jude Law) are the best parts might as well be speaking

to me in a foreign tongue. And those who approach this movie from an auteurist perspective--viewing it simply as either a Stanley Kubrick

film (because he spent years developing it) or as a Steven Spielberg

film (because he took over the project after Kubrick’s death, at the

request of Kubrick’s family)—-can’t be viewing it correctly

either.

As a philosophical meditation on the differences between mechanical

and organic life, life and death, and mankind and the artifacts of

mankind, we can’t even say with confidence if

A.I. is the product of

a dead filmmaker or a living one, a piece of celluloid or an

experience, a warm tearjerker of Disneylike goo about the goodness

of human life or the chilliest and bleakest possible

parable about its futility. |

|

It’s sad to reflect that out of my ten selections

here, only the first on my list, The Crazy Ray, has much chance of

cheering you up as a happy sort of fantasy, which probably reflects

my current feelings about the times we’re living in. (I think we can

all agree that the happy ending of

Metropolis is by far the silliest

thing about the movie.) But I also have to admit that, for all its

terminal gloom about the human condition and the future of mankind,

A.I.

can only fill me with hope about the future of art. |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()