|

Coming up with my favorite box sets from abroad is a far cry from

compiling a list of my favorite films on DVD, foreign or otherwise,

even if some of my favorite films are represented here. The problem

is, as Mick Jagger puts it, you can’t always get what you want. To

start with an extreme example, my favorite Hou Hsiao-hsien film is

most likely

The Puppetmaster (1993), but my

least favorite of all the DVDs of Hou films in my collection happens

to be the Winstar edition of that film. It’s so substandard—-not

even letterboxed, and packaged so clumsily--that I’m embarrassed to

find myself quoted on the back of the box, especially with the

quotation mangled into tortured grammar.

I’ve aimed for a certain geographical spread as well as some generic

balance: popular comedies, art films, experimental films, and one

serial; DVDs from Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, and the

United Kingdom.

Admittedly, roughly half of my selections come from France, and a

quarter of them, to my surprise, comes from a single label, Gaumont—-maybe

because this blockbuster company seems to specialize in blockbuster

box sets. But it’s hard to think of artists more dissimilar than

Feuillade, Godard, and Guitry, so even here there’s pretty much of a

spread.

After much hesitation, I’ve decided to omit one awesome French box

set that lacks any sort of English translation—Alain Resnais’

Hiroshima mon amour (on Arte

Video)—even though I’ve unapologetically included another, Louis

Feuillade’s

Fantômas, as well as many

others that have a few untranslated features. But, just the same,

there are plenty of things that would make this missing item

delectable even if you don’t understand a word of French, such as

full-color reproductions of the letters, snapshots, and clippings

Resnais sent to screenwriter Marguerite Duras while scouting

Hiroshima locations, and three of Resnais’ major black and white

shorts. As a former Parisian who spent part of my film education

seeing many movies at the Cinémathèque Française without any sort of

translation, I can still recommend this activity over not seeing

some films at all.

The order of the list below is alphabetical, by title. I can’t

guarantee that all of these are still in print or available--some

are likely to be much harder to track down than others.

(NOTE: CLICK ON

TITLES, COVERS OR UNDERLINED TEXT FOR LINKS)

Compared to the Arte Vidéo boxset from France

HERE |

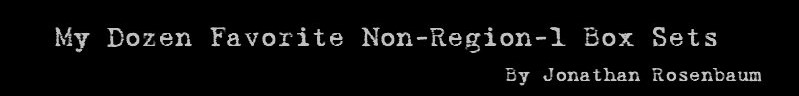

1)

Buster Keaton: The Complete Short

Films, 1917-1923

(Masters

of Cinema, four discs + 184-page booklet)

If you want a definitive edition of what some critics

have called the purest examples of Keaton’s comedy, look

no further. (James Agee, for one, wrote that “for plain

hard laughter,” the Keaton shorts are even better than

the features.) One of these early shorts--Moonshine

(1918), codirected by “Fatty” Arbuckle--is incomplete,

but the 31 other restorations are all intact, and

they’re a joy to behold. And the accompanying book gives

us, along with many illustrations, generous extracts

from Keaton’s autobiography and several interviews as

well as an extended critical roundtable on Keaton by

three top-notch critics, Jean-Pierre Coursodon, Dan

Sallitt, and Brad Stevens. Regrettably, I’ve only had

room on this list for one set from the superb Masters of

Cinema--an English series distributed by Eureka! that

also offers essential works by

Michelangelo Antonioni,

Fritz Lang,

Jean-Pierre Melville,

Kenji Mizoguchi,

F.W. Murnau,

Mikio Naruse,

G.W. Pabst,

Luchino Visconti,

and

Orson Welles, among

many others—-but if you’ve never seen an example of

their work, this release should provide an excellent

introduction. |

|

|

|

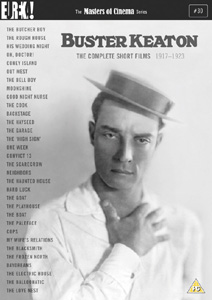

2)

Chantal Akerman Collection: Les

Années 70/De Jaren ‘70

(Cinéart, five discs)

Please note that this is the Belgian as opposed to the

French set devoted to Chantal Akerman’s most radical

period, an edition supervised by the filmmaker

herself--which is the only one that has optional English

(as well as Flemish) subtitles. The films included, all

digitally remastered, are her two earliest shorts,

Saute ma ville (1968) and La Chambre (1972),

and her first five features--Hotel Monterey

(1972), Je Tu Il Elle (1975), Jeanne Dielman,

23 Quai de Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975),

News from Home (1976), and Les Rendez-vous

d’Anna (1978). |

|

The extras are quite remarkable —-in most cases, major additions to

Akerman scholarship: recent long conversations between Akerman and

Babette Mangolte (her cinematographer on Jeanne Dielman),

Aurore Clément (her lead actress in Les Rendez-vous d’Anna),

and her mother Nathalia; a short 1996 interview with Akerman taken

from the French TV documentary Chantal Akerman by Chantal Akerman;

and, best of all, a feature-length 1975 documentary about the making

of Jeanne Dielman, including some fascinating video footage of

Akerman working with the title star, Delphine Seyrig. (This was made

during a period when video reportage of this kind was still in its

infancy, so the image quality here is fairly primitive and

rough-hewn, but the interest of the content more than makes up for

it.).

|

|

|

|

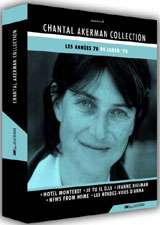

3)

The Chelsea Girls: un film di Andy

Warhol (Minerva Video, two discs + 66-page

bilingual booklet)

The challenge here was how to transport Andy Warhol’s

most commercial experimental feature to DVD without

losing its most essential aspects. Shot in 16 millimeter

between June and September 1966, the film consists of a

dozen reels adding up to 394 minutes or about six and a

half hours. But, as projected, the film lasts only half

that long, 197 minutes, because it’s designed for

simultaneous double-screen projection, usually with one

reel projected with sound and the other reel projected

silently.

|

How shifting or fixed the arrangement of reels is

supposed to be is a matter of some dispute. According to Warhol

critic Peter Gidal, “color film is projected on the left,

black-and-white on the right,” and “the two projectors are not

synchronized and therefore at each showing the left screen image

and the right screen image correspond differently.” According to

Stephen Koch in another book about Warhol, “Tradition, rather

than Warhol himself, has established the standard sequence of

reels,” and according to Jonas Mekas, who established precise

split-screen projection instructions, reel #2 on the left is

supposed to start five minutes after reel #1 on the right, and

the stretches of silence or sound or the occasional sound mixes

between two reels are all predetermined.

The letterboxed version offered here seems to strike a rough

compromise between these various versions. In a few cases we see

a particular diptych twice, enabling us to hear the sound of

each reel in turn while the adjacent reel runs silent. (There

are 16 chapters in all.) There’s also a second disc of extras

that includes Mekas’s 1982 Scenes from the Life of Andy

Warhol, a 2003 dialogue between Mekas and Paul Morrissey,

and three additional bits of English-subtitled commentary by

pontificating Italians—-Enrico Ghezzi, Mario Zonta, and Achille

Bonitao Oliva. (Ghezzi, in homage to Warhol, speaks in a

split-screen himself!)

|

|

|

4)

Coffret Charles Chaplin 10 DVD

(mk2 éditions/Warner Video, ten discs)

Why, you may ask, include the French edition of this

remarkable package when it’s also available as a

region-1 set in the U.S.? Because a great deal of care

and attention went into the French set, and the

differences count.

Both versions, of course, include all of Chaplin’s

features apart from The Countess from Hong Kong

(the last and least of them), as well as the seven

shorts comprising The Chaplin Revue, and also

many remarkable extras, such as commentaries by other

directors about individual Chaplin films—-most notably,

the Dardenne brothers on

Modern Times,

Claude Chabrol on

Monsieur Verdoux,

and Jim Jarmusch on

A King in New York.

So this is obviously a box set worth having in any form.

But it’s more worth having if the packaging allows you

to appreciate what’s there. |

|

Consider the handling of a fascinating extra that’s

included with Chaplin’s 1923

A Woman of Paris—-an

elaborate, half-hour amateur film of 1926, a spoof called

Camille, made in New York by one Ralph Barton and probably

featuring more famous people on both sides of the Atlantic (over

50 of them, in fact) than any other home movie ever made. This

was at the height of Prohibition, so there are loads of gags

about people getting soused. The title heroine is played by

Anita Loos, the flapper author of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,

and prominent parts are also taken by her director husband John

Emerson as well as Chaplin (who performs an encore of his famous

Dance of the Rolls from The Gold Rush); other prominent

actors include Paul Robeson, Ethel Barrymore, and Dorothy Gish.

The French edition of the DVD includes an elaborate guide to who

plays whom and when—-enabling us to discover, for instance, that

speakeasy owner Gas House Charlie is played by Theodore Dreiser,

Sherwood Anderson is the “ruined archeologist,” H.L. Mencken is

a Prohibitionist and Clarence Darrow is a Prohibition agent.

Sinclair Lewis plays the allegorical figures Love, Hate,

Despair, Adultery, and Greed, while Alfred A. Knopf, in costume

and makeup, is Abdul-el-Hamman, a white slave trader—-none of

which we’re likely to figure out if we have only the U.S.

edition to go by, where the packagers couldn’t care less about

any of this.

Perhaps my favorite extra on any DVD appears on the region-1 DVD

of D.W. Griffith’s

Orphans of the Storm

(1921). It’s a radio eulogy for Griffith delivered by Erich von

Stroheim when Griffith died, and it ends with Stroheim bursting

into tears. Imagine how diminished this speech might be if Kino

Video had decided that it didn’t matter who delivered the

speech, and therefore didn’t bother to mention it. That’s the

kind of treatment we get on the American edition of this box

set.

|

|

|

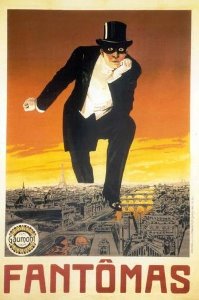

5)

Fantômas

(Gaumont, two discs + 32-page booklet)

For me, the most enjoyable movies made by anyone during

the teens are the French serials made for Gaumont by

Louis Feuillade--especially

Fantômas

(1913-1914),

Les vampires

(1915-1916),

Judex (1917), and

Tih Minh (1919). (Barrabas, which he made just after the

teens, in 1920, is also quite wonderful.) Tih Minh,

my favorite, hasn’t yet made it onto DVD, even though

it’s been restored, but both

Les vampires and

Judex are available

in fine editions in the U.S.

Fantômas is

available in both France and the U.K., in editions that

appear to be similar (the cover design is the same), but

I can’t vouch for this, because I have and treasure only

the French version. (Artificial Eye, the distributor of

the English version, has generally been reluctant to

send me review copies of their releases, unlike the

British Film Institute, Masters of Cinema, and Second

Run. According to English Amazon, their edition has the

same running time as the French, but I don’t know if it

has all of the same extras.) |

Properly speaking,

Fantômas isn’t a serial in the

same way the others are, because it consists of five feature-length

episodes rather than ten or a dozen short episodes, and some of these are

relatively independent of one another. (Their source is a series of

32 extremely popular novels by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre

that started appearing in 1911.) But insofar as these episodes

follow the exploits of a master criminal who goes under various

disguises and has a secret gang, Fantômas clearly offers a prototype

that the subsequent Feuillade serials would draw from in various

ways.

The fabulous Gaumont box set has almost as many tricks up its sleeve

as Fantômas himself. Go to the first menu on either disc, and after

you hear a footsteps and a key unlocking a squeaky door in the

darkness, three closed doors appear, asking you to choose one. Five

of these six doors stand for separate episodes; the sixth leads to

further extras. Then the following menu in the first five cases

presents you with a room containing a desk, with half a dozen

objects to choose from with your remote control--objects that are

near the desk or on top of it or inside one of the drawers. One of

the items on top of the desk is a reel of film, which leads you into

the episode itself (beautifully tinted, with an effective orchestral

score); all the others lead you into various hidden bonuses. (My

favorite of these is a bit of magical footage that shows you

Fantômas morphing through the spectrum of all his secret identities,

within a few seconds; some of the others are short texts or period

illustrations relating to the novels.).

|

|

|

6)

Histoire(s) du cinema (Gaumont,

four discs) (Cinefil Imagica, five discs;

www.cinefilimagica.com)

I have two separate editions of Jean-Luc Godard’s

intransigent and beautiful magnum opus. The first

one that appeared is the second one cited above, and the

most expensive box set I’ve ever purchased from

anywhere—even though it’s boxed fairly modestly, like a

set of CDs. It has better sound and image, and an

amazing feature that enables you to reference any moment

in this eight-part video with your remote control,

leading you to a citation (of the film a clip comes

from, the name of an artwork, and perhaps even the

source of each verbal quotation). The only glitch, and

it’s a major one, is that this feature is all in

Japanese, and the only optional subtitles available on

this Japanese set are also in Japanese. In fact, I’m not

even sure if the URL cited above will take you to this

set. (For that, you’re probably better off going to the

Japanese branch of Amazon. - Ed. see

HERE) |

|

The Gaumont version, on the other hand, has optional

English titles, though these are relatively spare, focusing

basically on the same portions of the text that Godard has

published in various languages in books included with the

soundtrack of

Histoire(s) du cinema on

CDs. As I’ve pointed out before on this site (HERE),

there is no completely satisfactory way to subtitle this

multilingual work, especially because no one, including French

speakers, can follow all of it, and even trying to translate

most of what gets said or printed would itself create an

impenetrable jungle for us to navigate. So this version is

pretty acceptable, although it’s a pity that Gaumont didn’t take

the trouble of subtitling any of the extras, which include

Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville’s feature-length 2 X 50 Ans du

Cinéma Français and two separate press conferences at

Cannes, in 1988 and 1997—apart from French subtitles to the

portions of the 1988 press conference that are in English. By

the way, there’s a third version of

Histoire(s) du cinema,

again with English subtitles, that Artificial Eye is supposed to

be bringing out soon (HERE),

if it hasn’t done so already.

|

|

|

7)

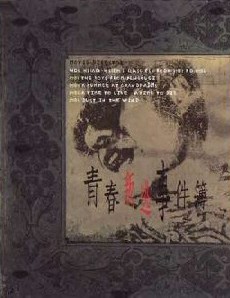

Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Classics

from 1983 to 1986 (Sino Movie, four discs + copiously

illustrated 52-page booklet in Chinese with some foldout

pages)

Some of my choices here are partly inflected by the

degree to which some box sets qualify as beautiful

objects. This is certainly the case with this gorgeous

and compact collection from Hong Kong, containing The

Boys from Fengkuei (1983), A Summer at Grandpa’s

(1984), A Time to Live A Time to Die (1985), and

Dust in the Wind (1984)—to quote the four titles

just as they’re written on the box encasing the elegant

fold-out container. All these films are impeccably

letterboxed and furnished with optional English

subtitles, so I couldn’t care less that the menus, apart

from the films’ English titles, are all in Chinese. This

is still very user-friendly, and the booklet attached to

the foldout container, like the color illustrations on

the discs themselves, is a pleasure even when one can’t

read the words. |

|

8)

Orson Welles’ Macbeth

(Wild Side Video, three discs + 80-page booklet in

French)

Macbeth may be my least favorite among Orson

Welles’ three feature-length Shakespeare films, with

neither the mystery of his

Othello nor the

human majesty of his

Chimes at Midnight.

But when it comes to a definitive DVD edition of any

Welles film, I don’t think there’s any contest. This has

everything you’d ever want to have: both versions of the

film (released respectively in 1948 at 114 minutes and

in 1950 at 85 minutes; both, one should stress, are

Welles cuts, even though the second one was occasioned

by Republic Pictures asking him for a redubbed and

shortened version); a newsreel recording of the last

four minutes of Welles’ 1936 “Voodoo” Macbeth,

staged in Harlem (which is the only sound-film record

that we have of any Welles stage production); and the

full 78-minute audio version of the play done for 78 RPM

records in 1940, with a cast of Mercury Theatre players

and a Bernard Herrmann score)—all of which is impeccably

restored. Then there’s more than an hour of additional

extras that are in unsubtitled French, although the

illustrations in some cases are likely to hold your

interest. Most of these are discussions done separately

by Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas, the two

foremost French Welles scholars--whose excellent and

very up-to-date book,

Orson Welles at Work,

which they wrote together, was published in English

translation earlier this year.

|

|

|

9)

Rendez-vous à Bray

(Boomerang Pictures, two DVDs + one CD + 88-page

paperback novel in French, Julien Gracq’s Le Roi

Cophetua, + 36-page bilingual booklet in French and

Flemish)

This is surely the most obscure item here, but it’s such

a lovely film—-made in Belgium in 1972--and it receives

so much loving care from the friends of the late

writer-director André Delvaux that it deserves to be

much better known. For one thing, it’s surely one of the

most erotic films ever made, featuring both Anna Karina

and Bulle Ogier at their most attractive. For another,

it’s steeped in nostalgia for more or less the same era

when Louis Feuillade’s serials were being made. |

|

Try to imagine a quiet blend of

Jules and Jim and

Gertrud filmed in

color (the cinematographer is the great Ghislain Cloquet,

who also did superb work for Demy, Bresson, Polanski,

and Penn)and you’ll start to get some idea of the mood

of this adaptation of a novella by post-surrealist

writer Julien Gracq. Most of it charts a mysterious

night in 1917 spent by a Luxembourgian pianist and music

journalist (Mathieu Carrière) who’s been summoned by a

friend, a soldier and composer (Roger van Hool), to his

house in a Paris suburb. The friend inexplicably never

appears, but the woman (Karina) who prepares dinner,

whose identity is never clarified, eventually takes him

to bed. There are also several flashbacks involving the

two friends as well as the soldier’s girlfriend (Oger),

a character who doesn’t exist in Gracq’s story.

Most of this box set, an exquisite labor of love, is in

French, Flemish/Dutch, and English-—prepared with

Delvaux’s input just a few weeks before his death.

Philippe Raynaert’s graceful 24-minute intro spells out

the contents, designed to show Delvaux’s close

involvements with painting, music, literature, and

cinema. All of these are evident in the feature,

explicated in Raynaert’s lecture, and further

represented, respectively, by Delvaux’s half-hour

With Dieric Bouts (1975); his 20-minute Moviola

(1985) about Frédéric Devresse (a composer he often

collaborated with) plus a CD with music (including

Brahms and Franck) and dialogue from the film; the Gracq

story, published with a preface by Gracq about Delvaux;

and Delvaux’s seven-minute 1001 Films (1989),

dedicated to Jacques Ledoux, the former director of the

Belgian Cinémathèque. (Delvaux used to perform piano

accompaniments to silent films there—-as the hero of

Rendez-vous is seen doing in one of the flashbacks,

at a commercial screening of

Fantômas, no less.)

There are also a couple of TV documentaries about the

film’s production from the 70s. |

|

10)

Sacha Guitry L’Age d’or 1936-1938

(Gaumont, eight discs)

By far the heftiest piece of merchandise being

considered here, this is a big box containing no less

than nine features on eight discs, which is all the more

remarkable when one considers that

writer-director-actor-personality Sacha Guitry-yet

another celebrity who turns up in the silent Camille

included in the Chaplin box set--made all these films

between 1938 and 1939! I haven't yet been able to

determine whether he was also doing any theater during

the same two-year stretch, but even if he wasn't, one

certainly couldn't fault him for being unproductive.

For the record, the nine features included here, all

provided with optional English subtitles, are Le

Nouveau Testament, Le Roman d’un tricheur

(many critics’ favorite), Mon Père avait raison,

Faisons un Rêve, Les Perles de la Couronne

(my own favorite, at least among those I’ve seen so far,

and, as a trilingual wonder that unfolds almost

simultaneously in French, English, and Italian, a

genuine tour de force), Le Mot de Cambronne,

Désiré, Quadrille, and Remontons les

Champs-Elysées. There are also loads of extras, all

unsubtitled, including interviews with such filmmakers

as Olivier Assayas, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, and

François Truffaut. |

|

When I ordered this set last Christmas, my reasoning was

that I was about to retire from my 20-year stint at

The Chicago Reader

and therefore would have plenty of time to plow my way

through this collection, improving my French in the

process. Now it’s half a year later, and I find that

I’ve become far too busy writing articles like this one

to even make a proper start. But hope springs eternal.

|

11)

16 Films de Luc Moullet

(Blaqout, four discs)

Luc Moullet remains one of the great, undiscovered

glories of French comic cinema as well as one of the key

Cahiers du Cinéma

critics who became a filmmaker (and, unlike virtually

all his colleagues, is still a film critic today). But

he’s always stood apart from his fellow critics as well

as his fellow filmmakers—-as a left-wing anarchist,

proud of his working-class and rural background (and

still keenly interested in some Hollywood directors

associated with the right, such as Cecil B. De Mille,

Josef von Sternberg, and King Vidor); as the only

Cahiers critic who

defended Luis Buñuel in the 50s, before he became

fashionable; as a minimalist director whose aesthetics,

economics, and ethics have always been closely

interrelated; and as an occasional deadpan actor in his

own post-Keaton, post-Tati comedies. It’s typical of

what might be called his radical modesty that even the

title of this director-approved collection is inexact;

there are actually eight films here, at least if one

counts the two short features comprising the fourth

disc, both counted as bonuses—-Moullet’s The Sieges

of the Alcazar (1989) and Gérard Courant’s The

Man of the Badlands (2001) a documentary about

Moullet. |

|

The official six are Brigitte et Brigitte (1966),

Les contrebandières (1967), Une Aventure de

Billy le Kid (1970), Anatomie d’un rapport

(1975), Genèse d’un repas (1978), and

Parpaillon (1992). All eight of these have optional

English subtitles except for Billy le Kid--a

crazed western starring Jean-Pierre Léaud and seemingly

inspired by both

A Duel in the Sun

and a fever dream—-and in that case, Moullet includes

his own English version of the film, A Girl is a Gun.

These are just about all of Moullet’s major features.

(The sole exception is his 1987

La Comédie du travail—already

released separately by Blaqout, unfortunately without

any subtitles.) They include even his best noncomedy,

his 1978 Origins of a Meal, a powerful political

documentary that tells you where three simple food

staples come from. An even more ideal box set would

include Moullet’s best shorts--three of which are

available elsewhere on DVD (at least if you look very

hard), in separate collections, again without subtitles;

and, to cite Agee on Keaton, “for plain hard laughter,”

these are even better than the features. But this

collection is still a nearly perfect introduction to his

work. (If you want to explore some of these films

separately, Facets Video has issued them in pairs on

single region-1 discs. Ed. see

HERE)

I’d recommend starting out not with Courant’s

documentary but with The Sieges of the Alcazar--a

sweet and hilarious tale of a sexual grudge match in the

50s between a male

Cahiers du Cinéma

critic and a female leftist critic for the rival

magazine Positif, which takes place at a small

neighborhood cinema playing a Vittorio Cottafavi

retrospective. You might even call it a

A Duel in the Sun

writ small. Apart from offering loads of badly dubbed

clips and the theme song from

Rio Bravo over the

credits, this appears to be a near-definitive account of

the rituals and agonies of French cinephilia during that

period. |

|

12)

Le vent nous emportera

(The Wind Will Carry Us) (MK2 éditions, two

discs)

Here’s something else you can readily find in the U.S.;

New Yorker Video offers a ho-hum version of it. But I’m

mainly listing this French double-disc edition of my

favorite Abbas Kiarostami feature (1999), his last to

date to be shot on 35-millimeter, with optional English

subtitles on everything, because of the two

documentaries it includes on the second disc—A Film

Lesson by Abbas Kiarostami, 52 minutes long, and,

even more, Yuji Mohara’s 90-minute A Week with

Kiarostami, which in some ways is the most

informative and revealing “making of” documentary I’ve

ever seen. And this two-disc set is the only place I’m aware

of where you can find it. |

|

|