|

It might be argued that

many of the most famous and celebrated westerns qualify as eccentric

in one way or another.

Rio Bravo mainly consists of friends

hanging out together; its memorable action bits are both infrequent

and usually over in a matter of seconds.

The Searchers often

feels like medieval poetry, and its director John Ford once

complained that parts of its score seemed more appropriate for

Cossacks than for cowboys. Even

High Noon has so many titled

angles of clocks and reprises of its Tex Ritter theme that you might

feel like you’re trapped inside a loop, and it’s hard to think of

many sequences more mannerist than the opening one in

Once Upon a

Time in the West.

The dozen

favorites that I’ve listed here are all basically auteurist

selections. I’ve restricted myself to only one per director

(although I’ve cited other contenders and/or noncontenders by the

same filmmakers), and included both ones that are available on DVD

and ones that aren’t but should be—or, in some cases, will be. The

order is alphabetical:

|

|

1.

The Big Sky (Howard Hawks,

1952).

This isn’t simply the only Hawks western that

doesn’t star John Wayne (not counting his uncredited and

piecemeal work on

Viva Villa! and

The Outlaw),

or the only black and white one apart from

Red River.

It’s uncharacteristic in many other ways. By dealing

with trappers and explorers traveling up the Missouri

River from St. Louis to Montana in the 1830s, it’s more

a riverboat story than a horse opera, with a good many

French Creole characters (“Speak English, hoss,” is a

recurring line from Arthur Hunnicutt’s Uncle Zeb, the

team’s leader). It’s also the only Hawks films in which

Native Americans are important (not counting the demonic

white brats who play Indians in the next two films he

made,

Monkey Business and “The Ransom of Red Chief”

in O. Henry’s Full House). Furthermore, its two male

leads might be described as the most Hawksian team

player of all (Dewey Martin as an ornery, racist hick)

and the least Hawksian team player of all (Kirk Douglas,

too individualistic by temperament to belong to any

team). |

Part of what I treasure about this mysterious

epic relates to the mysterious bonds that form between these two

pals and a captured Blackfoot princess (Elizabeth Threatt, said to

be of Cherokee and English descent) who speaks not a word of their

language, or vice versa. For a director as conservative and as

habitually racist as Hawks, the warm and utopian three-way

understandings generated between this unlikely threesome, especially

when they spend some time together apart from the other characters,

now seem not only multicultural but also downright countercultural.

Even though you have to order this movie from

France or

Germany,

it’s worth it.

|

2.

Canyon Passage (Jacques

Tourneur, 1946).

It’s

astonishing that not even one of the westerns of

Tourneur—-Canyon Passage (1946),

Stranger on

Horseback (1955),

Wichita (1955), or

Great

Day in the Morning (1956), or either of his fine

proto-westerns, the southern

Stars in My Crown

(1950) or the Argentinian

Way of a Gaucho

(1952)—-is commercially available at present. So let’s

work our way down the list and start clamoring for the

first, shot in gorgeous color in Oregon. It’s probably

the best known as well as the most complex, and in many

respects it’s the most impressive. The cast includes

Dana Andrews, Susan Hayward, Brian Donlevy, Hoagy

Carmichael, Ward Bond, Andy Devine, and Lloyd Bridges.

In his superb

The Cinema of Nightfall: Jacques

Tourneur (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998),

Chris Fujiwara, who plausibly calls it “one of the

greatest westerns,” devotes 13 pages to it. |

|

|

3.

Dead

Man (Jim Jarmusch, 1995).

Having written a

short book (BFI

Publishing, 2000) about this black and white post-western, Jarmusch’s best movie to date, I couldn’t dream of omitting it from

my list. It’s the only western I know that assumes Native Americans

are part of the audience (and even addresses them with a few unsubtitled jokes). It’s the Johnny Depp film in which the actor’s

resemblance to Buster Keaton seems most suitable. (He plays an

accountant from Cleveland called William Blake). His costar, Gary

Farmer, creates the richest and warmest character in any Jarmusch

movie (as Nobody, a Native American outcast who’s half Blood and

half Blackfoot).

Dead

Man has the last film performance of

Robert Mitchum and a sublime improvised score by Neil Young, as well

as wonderful bits by Billy Bob Thornton, Lance Henrikson, Mili

Avital, and Iggy Pop. It’s a meditation about death that’s poetic

and scary, and an unvarnished view of frontier

capitalist America that’s both contemporary and

devastating. I suspect it’s the latter characteristic

that has freaked out some (American) viewers the most.

|

|

4.

Forty Guns (Samuel Fuller, 1957).

Fuller’s first two films,

I Shot Jesse James

(1949) and

The Baron of Arizona (1950), are westerns, but

it’s his next two westerns, both made in

1957, that are the most interesting,

Run of the Arrow and

Forty Guns. Only the latter is available, but it’s probably the

best and craziest anyway. Shot in black and white CinemaScope in

less than ten days (according to Jean-Luc Godard, who wrote the

first French review), it stars Barbara Stanwyck as the boss lady

with forty guns (or is it studs?) on her ranch. Fuller’s preferred

title was The Woman with a Whip. This contains one of the

lengthiest takes and tracking shots in the history of Hollywood, but

it’s the violence and the hysteria that one mainly remembers.

(Recalling the way a sexy gunsmith playfully points a shotgun at her

boyfriend, Godard included an homage with Jean-Paul Belmondo and

Jean Seberg in his

Breathless.) With Barry Sullivan and Dean

Jagger.

|

|

|

5.

The Gunfighter (Henry King, 1950).

King--who lived to the ripe age of 96, and was almost 30

when he directed his first film in 1915--had a

distinguished career in the silent period with a special

feeling for Americana. This reputation eventually became

tarnished when he wound up with too many mediocre

assignments as a journeyman director at Fox. But the

probable peak of his late period is this sensitive and

deeply felt demystification of the classic western,

starring Gregory Peck as an aging gunman with a period

moustache who finds himself menaced and beleaguered by

his own notoriety, including young toughs who want to

make their mark by outdrawing him. A moody character

study in black and white with more feeling than action,

this predictably lost money at the boxoffice, which is

probably why it hasn’t yet surfaced on DVD except for in

the

U.K., but along

with

Track of the Cat (see

below), it’s one the greatest art westerns, miles ahead

of the pompous and campy

Shane. Karl

Malden runs the saloon and Millard Mitchell is the

sheriff. |

|

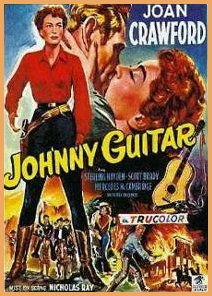

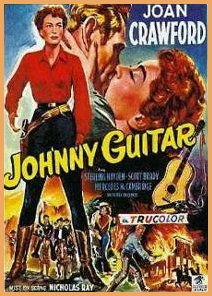

6.

Johnny Guitar

(Nicholas Ray, 1954).

“The

Beauty and the Beast

of Westerns,”

François Truffaut once called it—-perhaps thinking of

the fairy-tale waterfall leading to Scott Brady’s

hideout. (For the extra-observant, the word “God” is

scrawled on a nearby tree, for no better reason than to

express Ray’s swagger--or maybe the same feeling for the

cosmic that informed the planetarium in his

Rebel without a Cause

the following year.) This is the first truly hip

western, the 50s movie that was most explicit about

attacking the McCarthyite witch-hunts, and a baroque

stylistic exercise in terms of mise en scène and

cadenced dialogue. It sometimes seems to be on the verge

of breaking into a musical, with the title hero

(Sterling Hayden) pitted against The Dancing Kid

(Brady), and Vienna (Joan Crawford) constituting what

they’re fighting about. It’s also the first color film

on which Ray had artistic control—-consider how

flamboyantly he can brandish a teenage boy’s yellow

shirt, or what he does with the blazing fire that

sexually excites the perverse villainess (Mercedes

McCambridge) when she’s burning down Vienna’s saloon.

She’s a figure out of Greek tragedy rather than a

musical, so maybe this is the movie that taught the

French New Wave how to mix genres. |

|

|

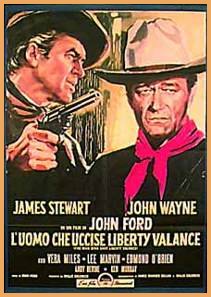

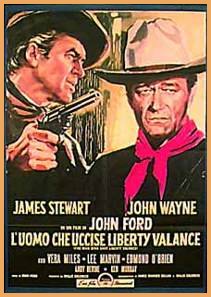

7.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

(John Ford, 1962).

John

Ford uses John Wayne, James Stewart, Vera Miles, Lee

Marvin (the title villain), Edmond O’Brien, John

Carradine, John Qualen, Andy Devine, Woody Strode, and

Strother Martin, among others, to recollect and rethink

his own career as a maker of westerns and what all those

legends he was helping to perpetuate meant. What he

comes up with is ambivalent, complex, and so clouded

with ambiguity about the misperceptions of history and

heroism that Andrew Sarris called his essay about this

black and white film “Cactus Rosebud”. It’s also

a kind of melancholy ghost sonata. If you’re getting a

little tired of black and white westerns on this list,

be assured that this is the fifth and next to last. |

|

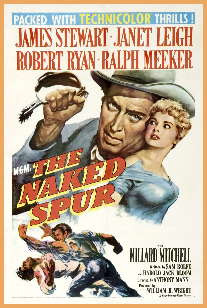

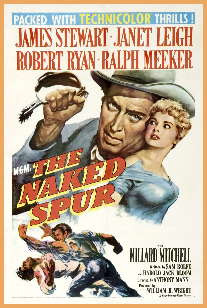

8.

The Naked Spur

(Anthony Mann, 1953).

And for natural splendors in color, you couldn’t do

better than this gorgeous piece of landscape art, shot

almost entirely in exterior locations in the Colorado

Rockies. James Stewart plays a rather nasty and troubled

bounty hunter—-a character diametrically opposed to his

civilized lawyer from the east in

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance—-and

it’s characteristic of Mann’s best and most elemental

western that, along with the four other characters, he

never changes his clothes even once. (The other four are

Janet Leigh, Robert Ryan, Ralph Meeker, and Millard

Mitchell, and the shifting dramatic geometry in terms of

alliances and conflicts is part of what makes this film

so brilliant.) Perversely, it’s both Mann’s greatest

western and the last major one to come out on DVD,

finally appearing in a

James Stewart box

set this August. |

|

|

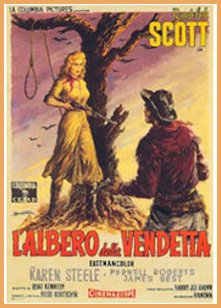

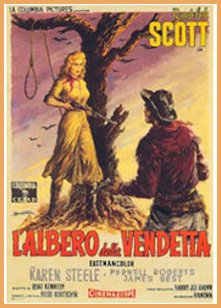

9.

Ride Lonesome (Budd

Boetticher, 1959).

If you start toting up the spectacular lacunae so far in

westerns commercially available on DVD, the five Ranown

westerns made by Boetticher with Randolph Scott have to

be somewhere near the top of the list. “Ranown” was a

production company named after the first three letters

of Randolph Scott’s first name and the last three

letters of the last name of Harry Joe Brown, Scott’s

coproducer. The only “Ranown” western on DVD--Seven

Men from Now (1956), recently

restored--isn’t bad, and it comes with a documentary

about Boetticher. But technically it isn’t a Ranown

western, though it’s often called one, because the

production company was John Wayne’s, and Brown wasn’t

connected to it. (Another ersatz Ranown western is Sam

Peckinpah’s 1962

Ride the High Country,

which is said to “sum up” the cycle, and is also

available.) And I wouldn’t call

Seven

Men from Now

the best of the Boetticher-Scott collaborations either.

|

I’ve selected

Ride Lonesome

because it’s in ‘Scope and, if memory serves, is more cheerful

(despite its title) than

Comanche Station (1960),

another ‘Scope film that ended the series.

Buchanan Rides Alone

(1958), a western about greed which preceded both, is my other

favorite (although I still have an abiding affection for the 1969

A Time for Dying, one of

Boetticher’s most unsung oddities, with Audie Murphy). The other two

Ranown westerns are

The Tall T and

Decision at Sundown, both

1957. It’s so hard nowadays to see any of them that I might shift my

allegiances if I saw them all again, but

Ride Lonesome

has two other pluses: an intricate Burt Kennedy script and the first

film role of James Coburn.

|

10.

The Shooting (Monte

Hellman, 1966).

The

only truly avant-garde western on my list (although

Johnny Guitar

arguably comes close), scripted by Carole Eastman under

the pseudonym Adrian Joyce. Hellman shot it over about

18 days, back to back with the somewhat more

conventional western

Ride in the Whirlwind,

and then spent about half a year editing both. Brad

Stevens’ excellent

Monte Hellman: His Life and Films

(Jefferson, NC/London: McFarland & Company, 2003) links

this odd movie, which he calls Hellman’s first

masterpiece, to Samuel Beckett’s

Waiting for Godot,

but I’m more prone to view it as the best western Alain

Resnais never made. It’s also the first movie Hellman

made with his most quintessential actor, Warren

Oates--who went on to play other indelible parts in

Hellman’s

Two Lane Blacktop

(1971),

Cockfighter (1974),

and his last western to date,

China 9, Liberty 37

(1978)—-and Oates’ memorable costars are Jack Nicholson

(who coproduced the film with Hellman), Millie Perkins,

and Will Hutchins. If it weren’t so funny in its

inimitable absurdist way, I suppose one could call it

pretentious, but only at the risk of missing all the

scary fun. |

|

|

11.

Terror in a Texas Town

(Joseph H. Lewis, 1958).

The

underrated Lewis, best known for his wonderful 1949

nonwestern

Gun Crazy, directed

other singular westerns apart from this exceptionally

weird one in black and white ‘Scope--including a couple

with Randolph Scott,

A Lawless Street

(1955) and

7th Cavalry (1956),

and

The Halliday Brand

(1957).

Terror in a Texas Town

is singular both for its unabashed anticapitalist

theme—-it was written pseudonymously by the blacklisted

Dalton Trumbo, who used Ben Perry as a front--and for

some of the worst acting ever to be found in a good

movie (check out especially Nedrick Young as the

gunslinger heavy). But I hasten to add that Sterling

Hayden, the star, is exceptionally fine. He plays a

peaceable Swedish seaman from the east who turns up in

the very corrupt title town to visit his father, a

farmer, only to find that he’s just been coldbloodedly

gunned down. Stalking the killer with a harpoon instead

of a rifle, he cuts a formidable figure.

|

|

12.

Track of the Cat

(William Wellman, 1954).

The strangest thing of all about this

singular art western by a hard-nosed veteran (whose other westerns

include

The Ox-Bow Incident,

Yellow Sky,

Westward

the Women, and

Across the Wide Missouri) is that John

Wayne produced it. Reportedly, after Wellman made Wayne a fortune by

directing him in

The High and the Mighty, Wayne said, in

effect, “Anything you want, Bill,” and Wellman chose to film a

first-draft adaptation by A.I. Bezzerides (Kiss Me Deadly) of

a symbolic William van Tilburg Clark novel set in Nevada, filmed in

color and ‘Scope but designed mainly in black and white. A

claustrophobic tale of a snowbound, neurotically dysfunctional

family whose bickering siblings include Robert Mitchum, Teresa

Wright, and Tab Hunter, and whose parents are an alcoholic and a

prude, it could be described as the American

Ordet--and it

includes a Dreyerlike funeral partially shot from the viewpoint of

the corpse in the ground. One wonders what Wayne might have thought

when he saw this wonderful picture. But the bottom line in this case

is that it’s great not because it’s eccentric but in spite of the

fact that it is. |

|

|