|

Some genres are a lot more elastic than others. Our notions of what

a Western or a musical consists of are reasonably firm. But

thrillers tend to be all over the place, overlapping at various

times with crime films, adventure films, heist films, noirs, mystery

stories, spy stories, melodramas, and even comedies, period films,

and art movies—-to propose a far from exhaustive list.

In order to demonstrate this overall versatility, I’ve come up with

18 recommended titles that I’m listing and briefly describing below,

in alphabetical order. A dozen are in English, three are in French,

and one apiece is in German, Italian, or Japanese. All but two are

currently available on DVD, although in at least one case you’ll

have to go beyond American sources in order to acquire it. And

ironically, the two that are unavailable are both Hollywood

classics—-one more indication of the degree to which some of the

major studios and/or the inheritors of their treasures still don’t

have a very clear idea of what they possess and keep out of reach.

(NOTE: CLICK ON

TITLES, COVERS OR UNDERLINED TEXT FOR LINKS)

|

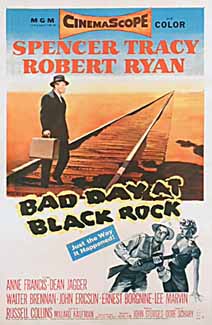

Bad Day at Black Rock.

My favorite John Sturges picture, an MGM CinemaScope

release of 1955, pits a slightly disabled Spencer Tracy

(he has use of only one arm, but knows karate) against

virtually an entire small southwestern desert town. The

bad day commences when he arrives at the sleepy train

station, seeking to find out what happened to a Japanese

friend of his, a World War II buddy, and nobody wants to

talk to him. Ernest Borgnine plays one of the local

toughs who tries to dissuade him from his quest by

pouring gobs of ketchup all over his food in a greasy

spoon diner, and what Tracy winds up doing in self-defense--a

burst of violence as neatly choreographed as anything

you’d find in Howard Hawks—-is alone worth the price of

admission. But Tracy’s main adversary proves to be

Robert Ryan, and it takes most of the movie’s 81 minutes

for all of the town’s baroque entanglements to be

revealed.

|

|

|

|

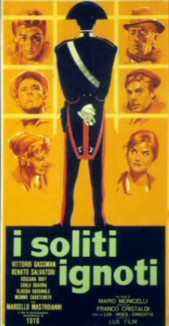

Big Deal on Madonna Street.

The only pure comedy on my list is also the only pure

heist movie (unless one counts 5 Against the House, a

secondary recommendation), and so influential that that

you’ve probably already encountered certain gags from

it. (See, in particular, Crackers, the American

remake--probably the worst film Louis Malle ever

made--as well as Woody Allen’s massive borrowings in

Small Time Crooks.) This is only fair, because Mario Monicelli’s hilarious 1958 farce about a team of

bungling burglars trying to break into a safe full of

jewels is itself an elaborate parody of two very popular

heist films of the 50s, John Huston’s

The Asphalt Jungle

(1950) and Jules Dassin’s

Rififi (1955), the second of

which was clearly influenced by the first. Like many of

the best Italian movies, this is strong above all for

its characters, and the cast—-which includes Marcello

Mastroianni, Claudia Cardinale, and Vittorio Gassman—-is

first-rate.

|

|

|

|

|

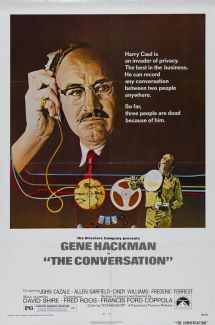

The Conversation.

This is perhaps the best-known item on my list, but as

the best of all thrillers about

surveillance—-specifically, about an “electronic

surveillance” sound technician working out of San

Francisco, played by Gene Hackman in what may be his

greatest performance—-it deserves to be still better

known. (It didn’t “perform” all that well at the box

office when it came out in 1974, which may account for

its relative obscurity.) Francis Ford Coppola wrote,

directed, and produced it, and it remains my favorite of

his films, even though it’s possible to conclude, after

listening to the DVD commentary of both Coppola and his

brilliant editor Walter Murch, that Murch may be the

film’s true auteur. Atmospheric, morally troubling, and

often suspenseful, this is the sort of movie you’re

likely to carry around with you long after you’ve seen

it. The excellent secondary cast includes John Cazale,

Allen Garfield, Cindy Williams, Frederic Forrest, and an

unexpected early bit part by Harrison Ford. |

|

|

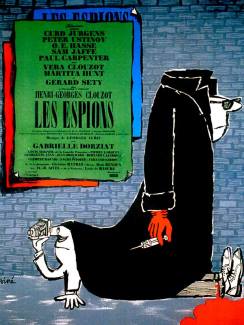

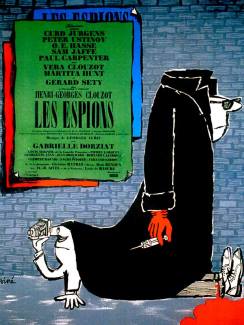

Les Espions. In

contrast to

The Conversation, this is possibly the least

well known of my selections, and a film I discovered

only recently, when I ordered a DVD of it from England.

It’s directed and cowritten by Henri-Georges Clouzot,

the only filmmaker responsible for two of my 18

selections (see

The Wages of Fear, below)—-a kind of

French Hitchcock whose view of the world was even

blacker and bleaker than Hitchcock’s. The title is

French for “The Spies,” and the setting of this very

strange and caustic 1957 picture is a run-down mental

asylum with very few patients in the sticks. The head

doctor there is offered a large sum of money from the

U.S. military in order to shelter a mysterious

physicist, and after he reluctantly agrees, a good many

international spies turn up as patients in the

establishment as well, and the paranoid Cold War

conspiracies keep growing from there in both size and

complexity. As I’ve suggested elsewhere, Clouzot’s

oddity may come closer to the absurdist humor of Franz

Kafka than any of the literal adaptations of his work,

such as Orson Welles’ version of

The Trial, and the

secondary cast is especially memorable: not only Clouzot’s wife Vera Clouzot (who also figured in his

better-known

Diabolique and

The Wages of Fear, but also

Hollywood actor Sam Jaffe (The Asphalt Jungle), English

actor Peter Ustinov (Lola Montes),

and German actor Curt Jurgens (Bitter Victory).

|

|

|

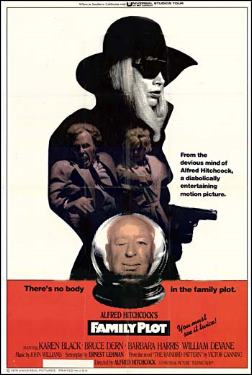

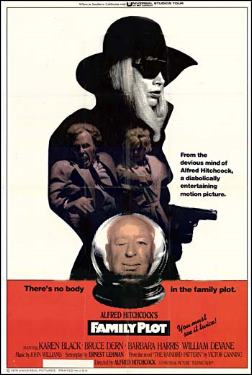

Family Plot. As long as we’re on the subject of Hitchcock and Hitchcockian suspense, consider this a special plug for his

underrated 53rd and final feature, frequently written off as “minor”

because it takes the form of light comedy (which is also the case

with his less suspenseful but equally underrated

The Trouble With

Harry).

Yet unlike Hitchcock’s other late films (Torn Curtain,

Topaz, and

Frenzy),

which tend to break up into set pieces, this is all of a

piece—-a superbly integrated and intricate as well as charming piece

of mischief built around two romantic couples (Bruce Dern and

Barbara Harris, Karen Black and William Devane) and a “double” plot.

The script is by Ernest Lehman, who scripted the very best of

Hitchcock’s breezy comic thrillers,

North by Northwest—a title I’ve

omitted here only because, like my other Hitchcock favorite,

Rear

Window, it’s too well known to need anyone’s recommendation. When

the French critics of the New Wave (Chabrol, Godard, Rivette,

Rohmer, and Truffaut) insisted on taking Hitchcock seriously long

before anyone else did, one of their key pieces of evidence was

Hitchcock’s very intricate use of stories involving double plots and

rhyming shots, such as

Shadow of a Doubt (as analyzed by Truffaut)

and

The Wrong Man (as analyzed by Godard).

Family Plot places this

concept front and center, and Hitchcock plays with it brilliantly,

like a perfectly composed piece of music. |

|

|

|

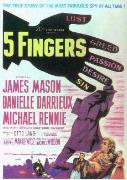

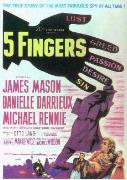

5 Fingers. This is one of the rare movies by Joseph L. Mankiewicz

where he doesn’t take a writing credit. The script of this ingenious

and entertaining spy thriller of 1952, another Cold War item, is

credited to Michael Wilson, and it’s a wonderful showcase for its

cast—-James Mason (in one of his best roles), Danielle Darrieux, and

Michael Rennie. An extra bonus: The score is by Bernard Herrmann. |

|

|

|

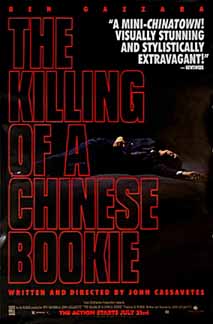

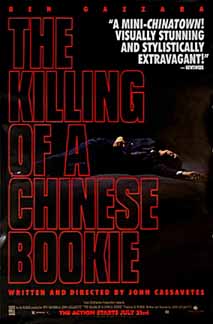

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. There are two versions of John Cassavetes’ postnoir masterpiece--first edited and released in 1976,

then recut and re-released in a shorter version two years later

after the first one failed miserably at the box office. (Lamentably,

the second version failed as well.) It’s hard to choose between

them, but I tend to opt for the earlier, longer, and, until

recently, harder to see of the two versions, both of which are now

available in

Criterion’s excellent Cassavetes box set. The hero,

Cosmo Vitali--a flashy owner of a Los Angeles strip joint,

beautifully played by Ben Gazzara, both a stupid asshole and a kind

of saint—gambles his way into serious debt, and finds he has

to fulfill a contract to bump off a Chinese bookie in order to settle

his accounts. This leads to one extended suspense sequence, but

basically this movie can also be read as a personal allegory by Cassavetes, a self-portrait about himself as an embattled impresario

and father figure to a precarious showbiz collective who has to do

dirty stuff in order to keep his family afloat (much as Cassavetes

had to act in Hollywood pictures in order to finance his own movies,

including this one). It even concludes--self-consciously but

magnificently –-with Cassavetes’ self-adopted theme song, “I Can’t

Give You Anything But Love,” clearly the motto of his entire work as

a filmmaker. |

|

|

|

M. As far as I’m concerned, Fritz Lang’s first talkie (1931) remains

not only his greatest film but also the best serial killer movie

ever made by anyone. It also has the best performance to be found in

any Lang film—-Peter Lorre as a crazed murderer of children who

terrorizes a city to such a degree that ultimately both the local

gangsters as well as the local police have to pool their resources

in order to track him down. The suspense we expect from such a story

is certainly present; but it’s also, as in the best Hitchcock films,

a kind of moral ambiguity designed to trouble and provoke us into

reflecting where we belong in Lang’s scheme of the way the world

works. The geometry of the plot, compositions, and editing is as

breathtaking as Lorre’s terrifying portrait at the dead center of

the film. |

|

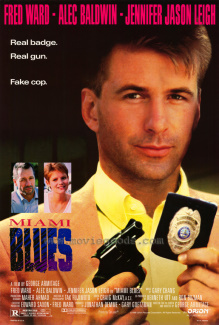

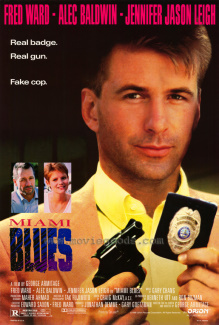

Miami Blues. The cult crime-thriller writer Charles Willeford

crowned his career by writing four superb novels centered around a

Miami-based homicide detective, Hoke Moseley: Miami Blues (1984),

New Hope for the Dead (1985), Sideswipe (1987), and

The Way We Die

Now (1988). Individually and collectively, they do almost as good a

job of describing “the way we live now” as John Updike’s four novels

about Rabbit Angstrom, written over a much longer period. My favorite among the Hoke Moseley novels—-certainly the scariest, and

possibly the best constructed—is Sideswipe. But Miami Blues is the

first, and George Armitage’s 1990 film adaptation is one of the best

literary adaptations I can think of. The cast is perfect: Alec

Baldwin as an ex-con and small-time thief who arrives in Miami,

hooks up with a local prostitute (Jennifer Jason Leigh), and winds

up stealing the gun, badge, and dentures of Moseley (Fred Ward) to

pose as a cop while pulling off more of his jobs. The humor and

pizzazz of this, as well as the use of locations, call to mind Godard’s

Breathless.

|

|

|

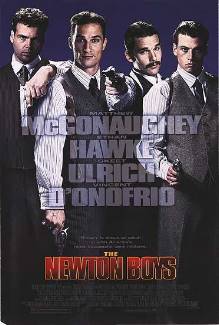

The Newton Boys. Many people have declared Richard Linklater’s first

big-budget movie (1998)--a period recreation of and tribute to the

most successful bank robbers in U.S. history, brothers from Texas,

who thrived between 1919 and 1924—-to be anything but thrilling. I

obviously don’t agree with them, but I have to admit that the very

notion of a gentle and relatively non-violent movie about bank

robbers who never killed anyone is almost a contradiction in terms,

at least when it comes to generic thrillers. This is part of

Linklater’s point—-a nongeneric point, one might say--and it’s why,

when I originally reviewed this film for the

Chicago Reader, I

compared it to Francois Truffaut’s

Jules and Jim, which has a

similar light and elegiac touch There’s also something about Linklater’s fascination with the way American looked in the teens

and 20s that inspires meditation rather than suspense. But insofar

as suspense in any movie is partially a matter of eagerly awaiting

what comes next, I have to say that this is a thriller that

continues to thrill me. |

|

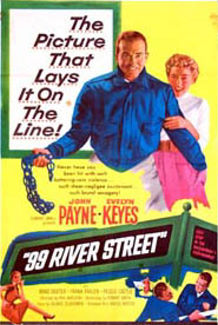

99 River Street. One of the most underrated thriller and noir

specialists in American cinema is Phil Karlson, the Chicago-born

director of

Tight Spot

(1955), 5 Against the House (1955), The Phenix City Story (1955), and

The Brothers Rico (1957), among many other gems.

The first of these features Ginger Rogers as a sassy

convict; the second is an ingenious Jack Finney

adaptation and sexy Kim Novak vehicle about a bunch of

college jocks who contrive a way to rob Harold’s Club in

Reno; and the third is my candidate for the best movie

ever shot on location in Alabama, while the fourth, as I

recall, is an excellent thriller about a former Mafia

bookkeeper (Richard Conte) trying to go straight.

Only the

first of these is available (in

Japan or the

UK!), and a

particularly regrettable absence is the earlier

99 River Street

(1953), which

follows the unpredictable and exciting adventures of a

boxer-turned-cabbie and cuckold (John Payne) over one crazy night in

New York City. Critic Dave Kehr once aptly called it "an example of

the kind of humble brilliance that often emerged from the American

genre cinema”; it costars Evelyn Keyes. |

|

|

Odd Man Out. James Mason, again at his near best, plays an Irish

revolutionary on the run in Belfast, meeting with a broad spectrum

of human responses ranging from indifference to empathy (once again,

over a single night). Carol Reed’s 1946 English thriller, adapted

from a novel by F.L. Green, is the artiest of all the films I’ve

selected, and it’s come to have a mixed reputation due to its

allegorical pretensions and some of its fancier visual conceits. But

as James Agee pointed out, it catches the feel of a city at night

with indelible poetry and intensity, and Robert Krasker’s black and

white cinematography is good enough to make you think of Orson

Welles’ work with Gregg Toland and Stanley Cortez on

Citizen Kane

and

The Magnificent Ambersons. The secondary cast—-including such

standbys as Cyril Cusack, F.J. McCormack, Robert Newton, Dan

O’Herlihy, and Kathleen Ryan--is sublime. |

|

Panic in the Streets. Before Elia Kazan became famous as a film

director (he was already a seasoned stage director), he made a

couple of interesting and effective thrillers shot on

locations—Boomerang (1947) in Connecticut and this taut tale, which

is even better, about a public health doctor (Richard Widmark)

trying to track down a bunch of thieves who may be infected with

bubonic plague, in New Orleans. Edward and Edna Anhalt won an Oscar

for their original story, and the backup cast includes Barbara Bel

Geddes, Paul Douglas, Jack Palance, and Zero Mostel. |

|

|

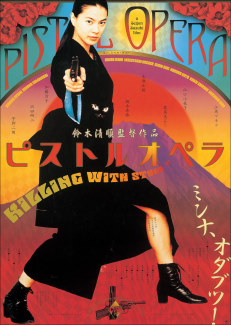

Pistol Opera.

Odd Man Out may be arty, but Seijun Suzuki’s belated

2001 color sequel to his 1967 hitman thriller

Branded to Kill is

positively insane. It’s also beautiful enough to take your breath

away; the opening credits alone pack in more gorgeous, graphic

inventiveness and dazzle than one is likely to find in most

features. Several generations of hitwomen comprise most of the major

characters, with top honors going to the ravishing Makiko Esumi as

Stray Cat--contriving to shoot her way from third to first place in

an obscure hierarchy of assassins as she proceeds through city and

country settings and various theatrical stages as well as dreamy

studio sets. Even if you can’t follow the story of this

choreographed pop fantasy—-and I managed to only at odd

junctures—-this is so deliriously pleasurable to look at and listen

to that you may not care. The subtitled Japanese dialogue,

incidentally, shifts on occasion to English, at least long enough

for recitations of Wordsworth and “Humpty Dumpty”. |

|

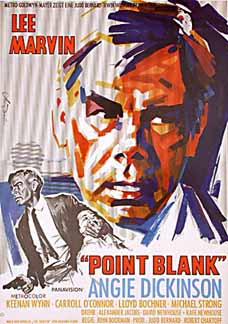

Point Blank. One more arty thriller—-the last one, I promise. But

it’s still John Boorman’s best feature, even though he made this in

1967, and it stars Lee Marvin in one of his ripest performances as

an ex-con who stoically emerges from prison looking for revenge,

often looking incongruous in various chic L.A. surroundings. The

handsome ‘Scope compositions and the tricky, Alain-Resnais-like

cutting are mainly what make it arty, along with some occasional

hints of allegory and/or parable. But much of this, especially

the violence (against objects as much as people), is deliberately

laugh-out-loud funny, and Marvin, Angie Dickinson, John Vernon, and

Carroll O’Connor all place the various shenanigans squarely in the

American vernacular. Godard’s working title for

Alphaville, Tarzan

Versus IBM, would apply just as well to this movie. |

|

|

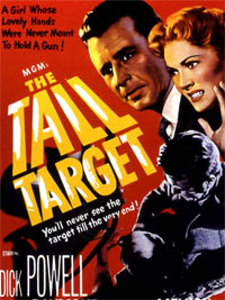

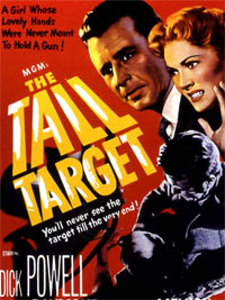

The Tall Target. It’s 1861, 90 years before this movie was made.

Abraham Lincoln has just been elected President, and an embattled

police detective (Dick Powell) boards an overnight New York train

bound for Washington to foil an early plot to assassinate him in

Baltimore the following day. Even though we know in advance that

this won’t happen, this being a paranoid, action-packed, atmospheric

thriller directed by noir and western specialist Anthony Mann, and

densely plotted, there’s all kinds of nasty skullduggery on this

eventful train ride. There’s no musical score, salty period

dialogue, and wonderful black and white cinematography by Paul C.

Vogel, full of steam, shiny rails, and claustrophobic enclosures;

Adolphe Menjou and Ruby Dee are especially good. Too bad that no one

has yet seen fit to make this MGM classic available. |

|

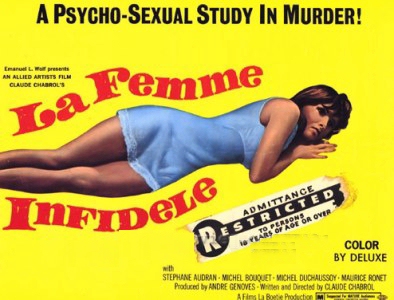

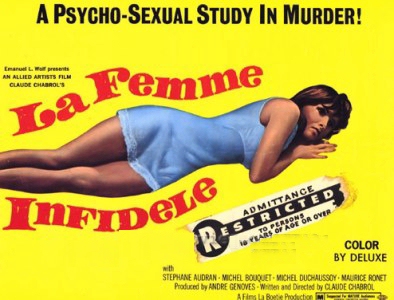

The Unfaithful Wife. Claude Chabrol’s

La femme infidèle comes from

1968, when he was specializing in celebrating while caustically

undermining French bourgeois family life. The setup is classic: a

cuckolded husband (Michel Bouquet) calmly sets about plotting the

murder of the man sleeping with his wife (Stephane Audran). Much of

this is deliberately as slow as molasses in its pacing, but never

boring. Chabrol’s ease with this material, and his way of bringing

more and more depth and insight to his subject, never falters, and

the ending manages to be both profound and unexpected. |

|

|

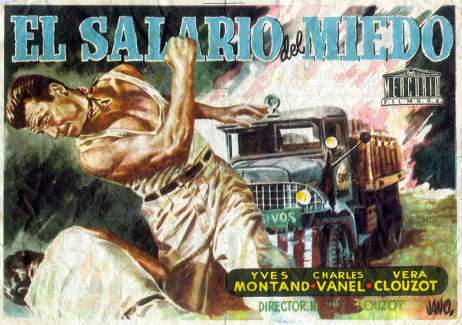

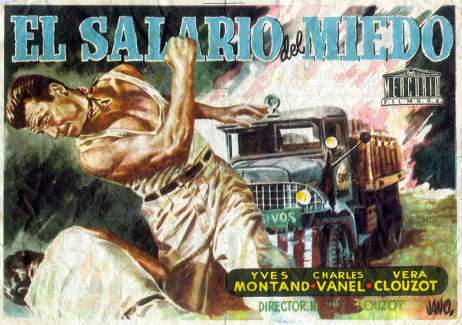

The Wages of Fear. Finally, the film I would pick as being the most

suspenseful of all the thrillers I know—-as well as one of the most grueling in terms of gritty details. It centers on four desperate

and unemployed Europeans (Yves Montand, Charles Vanel, Folco Lulli,

Peter Van Eyck) stranded in a dingy South American village that’s

exploited by a greedy American oil company. They agree to drive two

truckloads of nitroglycerine over 300 miles of bumpy, primitive

roads in exchange for $2,000 apiece—-at least if they’re alive at

the end of their run to collect it. When this 1953 existentialist

shocker originally opened in the U.S., 43 of its 148 minutes were

missing (including much of the agitprop about the oil company), but

the action was so strong that it was still a major hit. |

|

Practically all its footage has been restored on DVD,

and now it plays even better. There are things here one

can certainly object to—-misogyny, snobbery, and racism

among them—-as well as things one can applaud because of Clouzot’s

skill and audacity. (Among

other things, this is a passionate love story between

two of the men, Montand and Vanel).

And it’s been so influential that films as various as Cy Endfield’s

Sea Fury and Sam Peckinpah’s

The Wild Bunch would have been

unthinkable without its example. |

|