|

The first John Ford film I can remember seeing, probably encountered

around the time I was in first grade, was archetypal:

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon

(1949). Apart from its uncommonly vibrant colors, this had just

about everything a Ford movie was supposed to have: cavalry changes,

drunken brawls, Monument Valley, and such standbys as John Wayne,

Ben Johnson, Harry Carey Jr., Victor McLaglen, and Ford’s older

brother Francis; only Maureen O’Hara and Ward Bond were missing.

Ford was one of the very first auteurs I was aware of, along with

Cecil B. De Mille, Walt Disney, and Alfred Hitchcock, and what made

him especially distinctive was that he was apparently less

restricted than the others to a single genre. De Mille made

spectaculars, Disney did cartoons, and Hitchcock specialized in

thrillers, but a Ford movie could be a western, a war movie, or

something else.

The ten relatively

neglected Ford movies I’ve singled out here include a few that still

can’t be found on DVD. I might well have selected some others if I’d

seen them more recently (I’m currently looking forward to re-seeing

the 1945

They Were Expendable, for

instance), but I’d none the less argue that all of these are well

worth hunting down. Though a few of them are arguably as

quintessentially Fordian as

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon

(and three are honest-to-Pete westerns), most of the others are

sufficiently atypical to suggest that Ford is a richer, more

complex, and more versatile filmmaker than we usually assume. I’ve

also drawn attention in the following remarks to some of the abler

Ford commentaries and sources that have helped me find my way

through the intricacies of his work.

(NOTE: CLICK ON

TITLES, COVERS OR UNDERLINED TEXT FOR LINKS)

|

Bucking Broadway

(1917). Out of the approximately 70 silent films that

Ford directed, less than 15 are currently known to have

survived.

Bucking Broadway--one of the 11 or 12 westerns

he turned out in 1917, the year he started

directing--was rediscovered only eight years ago in a

Paris film archive, where it was hiding under a

different title. (It exists on DVD, but only as a

supplement to the “08,” “automne

2004” issue of the excellent, biannual

French film journal Cinéma--which has been including

DVDs of rare archival finds in every one of its issues

since 2003. - available

HERE).

Not

nearly as well known or as ambitious than Ford’s

Straight Shooting, which was shot earlier the same

year (and was found in a Czech film archive in 1969),

Bucking Broadway is

none the less delightful for its visual qualities, such

as the gorgeous landscape shots at the beginning and the

eye-filling action climax in which a team of Wyoming

ranchers are seen galloping down Manhattan’s Broadway

(actually downtown Los Angeles). |

|

|

|

Like

Straight Shooting, it stars Harry Carey--a

veteran of D.W. Griffith films who was almost twice

Ford’s age and served as his mentor when he was

getting started, as well as the star of over two

dozen of Ford’s early pictures. Mainly a light

comedy, it hinges on a romantic rivalry between

Cheyenne Harry (a cowboy character Carey played in

most of his Ford films) and a villainous city

slicker and cattle buyer played by Vester Pegg

(another Ford regular at the time) over a rancher’s

daughter (still another Ford regular, Molly

Malone). |

|

|

|

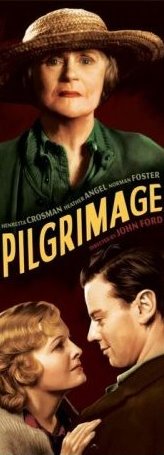

Pilgrimage (1933).

For many years, Ford specialists such as

Tag Gallagher and

Joseph McBride have been singling out this

uncharacteristic melodrama as one of the master’s unsung

masterpieces, even though it was a big commercial

success in 1933, and now that Fox has finally issued a

digital restoration, their claims seem wholly justified.

In fact, one of the best reasons for seeing the

restoration a second time is to follow McBride’s

excellent commentary, invaluable both for its factual

information and its critical insights. (McBride’s

observation that Ford likes to follow tragedy with farce

in the same pictures is especially helpful.) What’s most

unsettling is the poisonous spin it gives to what is

more often one of Ford’s sappiest themes, mother love.

The mother in this case, remarkably played by stage

actress Henrietta Crosman, is a selfish Arkansas widow

and farmer in 1918 who’s so traumatized by the prospect

of losing her son to the woman he loves and sleeps with

(this is pre-Code) that she spitefully signs him into

the army, where he’s instantly killed in World War 1.

She even states fairly explicitly in the dialogue that

she’d rather see him dead than lose him to another

woman, and after he dies, she refuses to recognize

either his illegitimate son or his mother.

After this

excruciating first act, the film unexpectedly turns into

a light comedy with occasional dark undertones once the

mother reluctantly agrees to join a group of “gold star”

mothers on a pilgrimage to their sons’ graves in France.

The film then starts to function on a good many

registers at once: as a devastating critique of war

propaganda, as a satire about yahoo Americans or

“innocents abroad” (a theme popularized by Mark Twain in

his first best seller), as a complex character study

that steadily grows in impact, and as a kind of parable

about moral redemption in which the mother finally comes

to terms with her own responsibility for her son’s

death. |

|

|

|

|

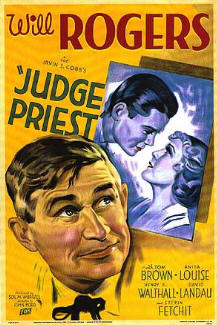

Judge Priest

(1934). “In

some ways,” Dave Kehr has written, “Judge

Priest marks the birth of the poet in

Ford.” There’s certainly no other Ford movie that I know

that comes closer to celebrating the idyllic 19th

century America of Mark Twain, expressing nostalgia for

the snug, leisurely life in closely interknit small-town

communities. But for me the real triumphs of this

laid-back masterpiece are the performances—especially

those of Will Rogers, Stepin Fetchit, and, in the film’s

courtroom climax, Henry B. Walthall (the “”Little

Colonel” of

The Birth of a Nation,

almost 20 years later.) Rogers, who was something of a

national sage when he made this movie, tends to be

underrated or at least taken for granted these days, but

listen to the amazing job he does in one scene of

imitating Stepin Fetchit, and notice how he pulls off

the impossible task in another of talking to his dead

wife without resorting to the sort of sentimentality

you’d expect. (This scene clearly anticipates the more

famous one in which Henry Fonda in the title role of

Ford’s 1939

Young Mr. Lincoln

speaks to Ann Rutledge at her graveside.) |

|

|

|

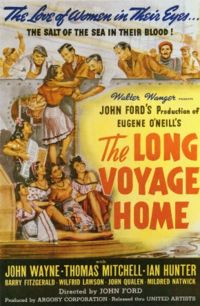

The Long Voyage Home

(1940). What is it about this moody, lyrical adaptation

of four short Eugene O’Neill “sea plays” by Ford regular

Dudley Nichols that makes Tag Gallagher and Joseph

McBride hurry past it as quickly as possible? Gallagher

gives it roughly the same amount of space as Sex

Hygiene---a half-hour army training film about venereal

diseases that Ford directed the following year--while

McBride calls it “extravagantly overwrought,” an epithet

I’d rather apply to Ford’s previous

The Informer and

his later

The Fugitive. Maybe

because the film was overrated in its own era there’s an

impulse to underrate it now, but I’m not buying into

this short-sighted rationale for a downgrade.

This

rambling, melancholy tale about the lonely lives of

merchant seamen is certainly expressionistic, and the

raw emotions it expresses are unusually direct for Ford.

O’Neill himself loved the film, and not because it’s at

all faithful to the letter of his work (the action has

been updated from the teens to the present), though it’s

as doom-ridden and as riddled with despair as one would

expect any good O’Neill adaptation to be. |

|

|

(The

title anticipates that of his posthumously released,

autobiographical masterwork,

Long Day’s Journey into Night.)

It has the most beautiful deep-focus cinematography by

Gregg Toland prior to

Citizen Kane; Welles’ own grand

gesture of sharing a title card in the credits with Toland came from Ford’s identical gesture in this film,

a year earlier. It also has John Wayne’s most

interesting performance when he’s playing someone other

than himself—as Ole Olsen, a young Swedish sailor who

misses his mother, with an accent that sounds authentic.

The remainder of the superb ensemble cast includes

Thomas Mitchell, Ian Hunter, Barry Fitzgerald, John

Qualen, Ward Bond, Wilfred Lawson, Joe Sawyer, and, in

her first work for Ford, Mildred Natwick.

|

|

|

|

|

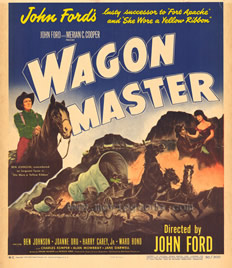

Wagon Master

(1950). Collectivity is one of Ford’s grandest and

most persistent themes, and it comes to the fore in this

small-scale western with no stars than remained one of

Ford’s personal favorites. The minimal plot focuses on

the various interactions between half a dozen separate

groups: ornery outlaws (who kill a bartender out of

spite in the pre-credits sequence), horse traders (Ford

regulars Harry Carey Jr. and Ben Johnson), traveling

Mormons (including a couple of more Ford standbys, Ward

Bond and Jane Darwell) who hire the horse traders to

help them out, show people (including Joanne Dru and

Alan Mowbray), lawmen, and Indians. Furthermore, this

may be the closest Ford ever got to making a musical,

another form that’s usually collective in spirit; the

Sons of the Pioneers--a vocal group that Ford would use

again on his next feature, the last and least of his

cavalry-trilogy films,

Rio Grande--sings

no less than four songs, and when cowpokes Carey and

Johnson decide to join the Mormons, their decision is

expressed by singing the movie’s theme song. |

|

|

|

The Sun Shines Bright

(1953). It seems significant that Ford’s favorites among

his own films tended to be the artier efforts that did

relatively poorly at the box office:

The Informer

(1935);

The Long Voyage Home

(1940);

The Fugitive

(1946—perhaps the most self-consciously composed of all

his pictures);

Wagon Master; and

the only non-independent feature in the bunch, a belated

spin-off of

Judge Priest

that he made for Republic Pictures, one of the cheaper

studios in Hollywood. This time he approaches the Irvin

S. Cobb universe without any stars--unless one counts

Stepin Fetchit, the only significant actor apart from

Francis Ford (in his last credited screen appearance)

who appears in both pictures, and a subversive purveyor

of southern black stereotypes whose subtly loaded

portrayals of servility masking cunning have often been

misunderstood. |

|

A lot of

Ford’s most deeply moving work could be described as a

meditation on social rituals, and this masterpiece

really comes into its own, despite a rather convoluted

plot, in its closing stretches, when it becomes nothing

but social rituals—a funeral, an election, and a parade.

The funeral and the parade (the latter in tribute to the

Judge Priest,

played here by Charles Winninger, who has recently

officiated at the funeral of a fallen woman), and

there’s an almost Faulknerian twist and irony in the way

that the funeral becomes triumphant while the

celebratory parade becomes almost unbearably sad and

tragic. This is one of the Ford films in which farce

precedes rather than follows tragedy, but the

bittersweet aftertaste is no less pungent. |

|

|

|

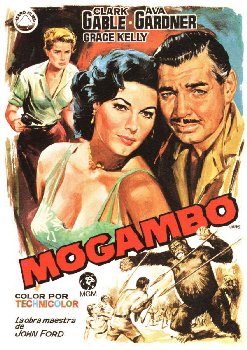

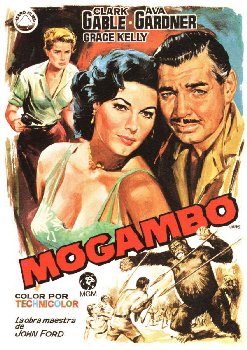

Mogambo (1953).

Probably the least characteristic Ford movie in my

selection isn’t very satisfying as an African action

picture. Ford, who was ill during part of the shooting,

left most of the animal footage to his second unit, and

the crosscutting between the Hollywood stars (Clark

Gable reprising his own role in this remake of the 30s

hit

Red Dust, Ava

Gardner, and Grace Kelly) and the apes or panthers looks

pretty artificial. If

Hatari! (1962),

where the actors and animals share the same shots, can

be viewed in many respects as Howard Hawks’ “answer” to

Mogambo (much as

Leo McCarey’s underrated Good Sam was his own “answer to

Frank Capra’s

It’s a Wonderful Life),

it’s worth adding that Gardner’s showgirl character here

is quintessentially Hawksian—both as the outsider we

identify with and the outspoken prattler who articulates

everything the other main characters are too repressed

to blurt out (as well as a maternal figure like Elsa

Martinelli in

Hatari! who coddles

baby elephants). In fact, what mostly makes this movie

click is erotic star power triple-distilled. Even more

than Hitchcock, Ford, who fought to cast Kelly in this

picture, knew how to make her sexy by treating her as a

sexually voracious volcano who’s constantly about to

erupt and no less constantly in denial about her desire.

Here she’s married to an anthropologist on a jungle

safari and lusting after animal trapper Gable, while

Gardner alternates as romantic rival and as good-natured

referee. |

|

|

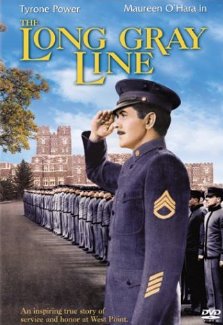

The Long Gray Line

(1955). In the recently updated edition of his 1986 book on

Ford (which is available only online

HERE), Tag Gallagher

reports that “The question once came up with Jean-Marie

Straub, what is an experimental film? Straub slammed his

fist on the table: `The

Long Gray Line! That’s an experimental

film.’” Well, not exactly—it’s a fictionalized biopic about

an Irish-born, not-very-smart-or-especially-capable phys-ed

instructor at West Point named Marty Maher (Tyrone Power,

playing opposite Maureen O’Hara). It’s also Ford’s first

picture in CinemaScope. On one level it’s a patriotic,

pro-military sob-fest with corny slapstick that

affectionately depicts then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower

when he was still a West Point cadet (played, naturally, by

Harry Carey Jr.), brimming with the kind of epic schmaltz

that Ford has often been faulted for. But it also has the

eerie ambivalence of Ford’s richest and most conflicted

work, focusing on failure, death, dissolution, and defeat as

it’s perceived through an utter mediocrity’s fading memory. |

|

|

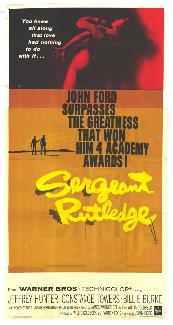

Sergeant Rutledge

(1960). Apart from serving as one of the key

inspirations and reference points for Pedro Costa’s

digital Portuguese masterpiece Colossal Youth

(2006), this unusually expressionistic western by

Ford---centered on the trial of a black cavalry officer

(Woody Strode) accused of rape and murder, and

structured around a good many flashbacks—is especially

notable for its very theatrical lighting schemes.

But it’s also potent, above all, because of the rare

emotion that Strode brings to the title part. The

political incorrectness that seems inextricably tied to

some of Ford’s finest insights and moments comes to the

fore in Strode’s climactic scene at the trial. Even if

some other aspects of this film are labored and

formulaic, this is a far more plausible attempt by Ford

to deal with ethnic persecution and racism than his

lamentable

Cheyenne Autumn

(1964)—which purports to make amends for Ford’s earlier

treatment of Native Americans and then ultimately avoids

dealing with them at all by treating them like ersatz

Holocaust Jews. |

|

7 Women (1965).

Patricia Neal was originally cast in the heroic lead

role of Ford’s apocalyptic final feature, which

uncharacteristically focuses almost entirely on female

characters--as an atheistic, hard-drinking, foul-mouthed

doctor in a Chinese mission during the 1930s. But she

became ill on her third day of shooting, and was quickly

replaced by Anne Bancroft, who does a terrific job.

Several critics have compared this character to Ava

Gardner’s in

Mogambo, and the similarity is evident

despite the fact that Bancroft plays a dedicated doctor

while Gardner plays a flighty showgirl. An unusual film

for Ford, it’s also clearly a very personal one about

the collapse of civilization and the sacrifices needed

for the survival of society. It was a resounding

commercial flop because MGM and most audiences didn’t

know what to make of it. It’s certainly more of a

shocker than any other Ford film I’ve selected, and the

less you know about it in advance, the better.

|

|

In one of

the most provocative and original pieces about Ford

that I’ve read, by Japanese critic Shigehiko Hasumi

HERE, a

persuasive, detailed argument is made about the

significance of throwing things in Ford’s films,

which functions emotionally and thematically (often

expressing a character’s solitude) as well as

formally. As Hasumi points out, 7 Women ends

with a powerful gesture of this kind, and “No other

filmmaker has ended his career with such mastery.”

But you’ll have to see the movie in order to

perceive why and how. |

|