|

Note: Just for the record, I’ve already written at one time or

another for this site about

Hallelujah, I’m a Bum!,

Judge Priest,

Love Me Tonight,

M,

The Man Who Could Work Miracles,

Pilgrimage, and

Vampyr -- which is the

only reason why I’m not doing so now.

So

add these seven titles to all of those found below (listed

alphabetically) and you’ll have 28 recommendations in all. And even

this list is very far from exhaustive. For instance, I haven’t even

mentioned Sacha Guitry, the witty playwright-filmmaker-actor whose

cinematic “golden age,” 1936-1938, comprising no less than nine

features (my favorite is the trilingual The Pearls of the

Crown), are all available with English subtitles in one

gigantic box set issued in France by Gaumont,

Sacha Guitry L’Age d’or 1936-1938.

But don’t get me started…

(NOTE:

HYPERLINKS ARE ON

TITLES, COVERS or BOLD, MAROON, UNDERLINED TEXT)

|

L’Atalante.

Jean Vigo’s only full-length feature (1934, 89 min.),

one of the supreme masterpieces of French cinema, was

edited and then brutally re-edited while Vigo was on his

deathbed, so a definitive restoration is impossible. But

the one carried out in 1990 is probably the best and

most complete we’ll ever be able to see, and it’s a

wonder to behold. The simple love-story plot involves

the marriage of a provincial woman (Dita Parlo) to the

skipper of a barge (Jean Dasté), and the only other

characters of consequence are the barge’s skeletal crew

(Michel Simon and Louis Lefebvre) and a peddler (Gilles

Margaritis) who flirts with the wife at a cabaret and

describes the wonders of Paris to her. The sensuality of

the characters and the settings, indelibly caught in

Boris Kaufman’s glistening cinematography, are only part

of the film’s remarkable poetry, the conviction of which

goes beyond such categories as realism or surrealism,

just as the powerful sexuality in the film ultimately

transcends such categories as heterosexuality,

homosexuality, and even bisexuality. Shot by shot and

moment by moment, the film is so fully alive to the

world’s possibilities that magic and reality seem to

function as opposite sides of the same coin, with

neither fully adequate to Vigo’s vision. |

|

|

|

Blonde Crazy.

The credited director of this 79-minute feature about

scrambling con artists is Roy Del Ruth, a solid company

man at Warners. But the true auteurs here are the

brilliantly proactive and expressive costars, James

Cagney and Joan Blondell -- as aided and abetted by the

screenwriting team of John Bright and Kubec Glasmon,

who worked on at least half a dozen other Cagney

vehicles during this period (not to mention just as many

Blondell features, including the underrated

Union Depot).

Packed with loads of plot twists and saucy repartee,

this unassuming comedy-drama probably offers more

Depression flavor than any other item in this survey

apart from the corrosive

Man’s Castle,

and it’s strictly an oversight that this hasn’t yet come

out on DVD. |

|

|

|

|

Boudu Saved from Drowning.

The 30s was an especially strong period for Howard Hawks

(represented by two films here), for Ernest Lubitsch

(also represented by two films), for Leo McCarey

(ditto), and, most of all, for Jean Renoir (represented

by three), who turned out 13 features during that

decade, the second, third, and thirteenth of which are

cited here. Boudu (1932), the third, stars the

great Michel Simon (see

L’Atalante,

above) as a mangy and unapologetic tramp saved from

drowning by a middle-class Parisian bookseller who’s

determined to reform and “civilize” him. A ruthless and

often hilarious tweaking of liberal delusions that

scandalized Bosley Crowther, lead film reviewer of the

New York Times, so thoroughly when it opened in

the U.S. for the first time (in 1967!) that he walked

out before the end, it continues to charm and provoke.

(By contrast, Paul Mazursky’s toothless 1986 remake,

Down and Out in Beverly Hills,

offends only those who care about the original.)

Renoir’s light-hearted comedy is also a kind of

irreverent celebration of Boudu’s sloth, diffidence, and

instinctually animalistic behavior. Renoir’s

off-the-cuff manner of shooting remains as carefree and

as fresh as the lead character.

|

|

|

|

City Lights.

My favorite Charlie Chaplin feature (1931) -- his first

sound picture, but not, properly speaking, his first

talkie--is also probably the one on which he exercised

the most patience and perfectionism, with almost two

years of shooting, countless retakes, and a recasting of

the female lead (with Georgia Hale, his female lead in

The Gold Rush, eventually replaced by

Virginia Cherrill, who was herself subsequently fired

and rehired, as the blind flower-selling street waif who

believes Chaplin’s Tramp is a millionaire). It’s also

quite likely the Chaplin feature that can boast the best

DVD extras, including one brilliant seven-minute gag

sequence that Chaplin deleted because it interfered with

the film’s overall architecture. Interestingly enough,

and significantly, the tragic final sequence, in

close-ups, rightly regarded as the most emotionally

wrenching sequence in Chaplin’s career, is edited in

such a way that it has glaring continuity errors, none

of which matter in the slightest because of the power of

his performance. |

|

|

|

|

Dishonored.

My favorite among the seven glittering Josef von

Sternberg features starring Marlene Dietrich, all of

them made between 1930 and 1935, is ironically the least

well known, and currently available only as a Swedish

import, although Jean-Luc Godard once included it in a

list of his ten favorite American films. It’s the second

American film Sternberg made with Dietrich, although it

was completed before he released the first (Morocco),

and in some ways it’s the most stylistically perfect of

all his sound features. In it, Dietrich plays X-27, a

character clearly inspired by Mara Hari — an Austrian

prostitute whose patriotism leads her to agree to spy on

the Russians (in particular, Victor McLaglen) and whose

activities ultimately lead to her death by firing squad.

|

|

|

|

Duck Soup.

From my favorite Sternberg to my favorite Marx Brothers

is less of a leap than it might initially appear to be,

especially because both deal with national issues in

abstract and rather absurdist terms. Leo McCarey’s only

encounter with Chico, Groucho, Harpo, and Zeppo is

memorable for many other reasons: it has fewer

distractions (i.e., gratuitous musical and romantic

sequences) than any of the other Marx Brothers movies,

more purely visual delights with links to silent cinema

(above all, the sequence with multiple Grouchos), and as

a wholesale ridicule of everything that leads to and

justifies warfare, it has the most bite as satire as

well as the most free-wheeling spirit. |

|

|

The Great Consoler

and

Ivan.

I’m cheating a little here by including in a single slot my

two favorite early-sound Soviet pictures, both still

woefully unavailable on DVD. (Thankfully, some other

innovative gems from this period are available now,

such as Boris Barnet’s

Outskirts,

Vsevolod Pudovkin’s

Deserter,

and Dziga Vertov’s

Enthusiasm.)

Both are pretty wild and adventurous, but the first of these

(1933), by Lev Kuleshov, is a true mind-boggler. It leaps

freely between three blocks of material: (1) In prison for

embezzlement, William Sydney Porter, better known as O.

Henry, is persuaded by the warden to convince a fellow

prisoner, safecracker Jimmy Valentine, to open a locked bank

safe without explosives in order not to destroy the papers

inside, after the banker, who knows the combination, skips

town with the funds. Valentine can do this only by painfully

filing down his fingernails to sensitize his fingers, but

the warden promises to grant him a pardon in return.

Meanwhile, Porter is so impressed by Valentine’s skill that

he writes a famous short story, “A Retrieved Reformation,”

romanticizing Valentine’s heroic exploits. But then the

warden, reneging on his promise, refuses to release

Valentine, forcing Porter to realize in despair that he and

Valentine have both been exploited. (2) “A Retrieved

Reformation,” recounted in parody form, as a Russian-style

western. (3) The effect of this story on one reader, Dulcie

(Alexandra Khokhlova, Kuleshov’s wife), a shopgirl who is

being forced to prostitute herself by the same cop who

convinced the prison warden to exploit Valentine’s gifts.

Even though Porter’s escapist yarn falsifies the truth, it

also inspires Dulcie to shoot the cop when he tries to

exploit her in turn….Ivan

(1932), the first talkie by the great Ukrainian filmmaker

Alexander Dovzhenko and a rapturous audiovisual poem,

supposedly celebrates the building of a huge dam on the

Dnieper River but never even bothers to show us the

completed structure; there are three separate characters

named Ivan in the picture and a great deal of wonderful

comedy….Both these masterpieces were unjustly denounced in

Russia as “formalist” when they came out, but that’s

certainly no excuse for Westerners to ignore them today.

|

|

|

I Was Born, But…,

Tokyo Chorus,

and

Passing Fancy.

Another form of cheating is to list all three of these

late silent pictures of Yasujiro Ozu, usefully packaged

together with optional piano scores by Criterion as “Eclipse

Series 10: Silent Ozu — Three Family Comedies”.

And the only reason why I’m listing I Was Born, But…

(1932) first, before

Tokyo Chorus(1931),

is that it’s my favorite Ozu film, full stop, even

though the other two aren’t far behind. My only

complaint about the packaging of these three

masterpieces is that calling them simply “family

comedies” short-changes them, even though all three

certainly have their hilarious moments. (In fact, the

opening sequence of the 1933

Passing Fancy

may be the funniest piece of slapstick Ozu ever filmed.

At a public music and storytelling performance, a stray

purse is surreptitiously picked up, investigated, and

then discarded by a succession of people in the

audience, who toss it around like a beanbag -- a string

of repetitions that overlaps with a series of frenetic

dances performed by many of the same people when they’re

bitten by fleas.) To call them all “family

comedy-dramas” might come closer to the mark, but this

label is also inadequate:

Passing Fancy,

which was inspired in part by King Vidor’s

The Champ

(1931), basically focuses on a day laborer who’s a

single parent and his son, a duo rather than a family

per se. The two are both played by Ozu regulars, Takeshi

Sakamoto (who in fact plays in all three features) and

Tokkan Kozo (who also plays in I Was Born, But…)

And it’s also worth emphasizing that

Tokyo Chorus

and

Passing Fancy

are both quintessential Depression films. |

|

|

Make Way for Tomorrow.

Due out from Criterion later this month, Leo McCarey’s

1937 heartbreaker, a particular favorite of Orson Welles,

didn’t win any Oscars, but when McCarey won an Oscar the

very same year for another movie,

The Awful Truth,

he tactfully suggested in his acceptance speech that the

Academy might have given it to the wrong picture.

There’s arguably no other film ever made anywhere that

deals more nakedly and candidly with the mistreatment of

old people (although Yasujiro Ozu’s best-known feature,

Tokyo Story,

was clearly influenced by it), and McCarey being McCarey,

this subject is milked for laughs as well as tears. It’s

also one of the most romantic movies ever made in

Hollywood, and the mounting tragedy of the final act is

devastating. The focus is on an elderly couple (Victor

Moore and Beulah Bondi) whose children don’t know what

to do with them, and rather than simply castigate them

for their cluelessness, McCarey understands their

dilemma as well as the situation of their parents; with

Fay Bainter, Thomas Mitchell, and Porter Hall. |

|

The Man I Killed

aka

Broken Lullaby.

Technically available from Spain, but not at all easy to

come by (and available only under its rerelease title),

Ernst Lubitsch’s atypical antiwar film (1932), the first

movie he ever cowrote with the great Samson Raphaelson,

follows a French soldier in World War ( the unjustly

forgotten Phillips Holmes) who is so stricken about the

German soldier he killed in the trenches that he travels

to the dead man’s village and meets his family. Only 76

minutes long, this has much the same elliptical style,

exquisitely detailed and articulated, that Lubitsch

brought to his better-known romantic comedies and

musicals, but the directness and sincerity of the story

apparently disconcerted audiences at the time. No

matter: the sentiments expressed are not in the least

bit dated today. With Lionel Barrymore and Nancy

Carroll. |

|

|

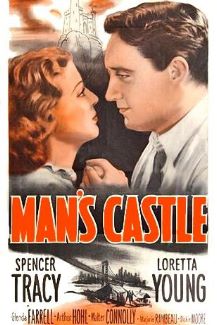

Man’s Castle

Considering the deluxe job done with the dozen-disc “Murnau,

Borzage and Fox,” it’s rather

stupefying to reflect that Frank Borzage’s most potent

sound picture remains unavailable everywhere. But this

was a movie made at Columbia, not Fox, and apparently

not even the star power of Spencer Tracy suffices to put

this item on the market. He plays a spiky scrambler in

Manhattan during the Depression opposite an equally

homeless Loretta Young. The two wind up living together

in a Hooverville shack (alluded to in the film’s ironic

title) where she becomes pregnant, and I suspect that at

least part of the problem may be the eroticism

(including some brief nudity) and the complete lack of

sentimentality that have always made this a beleaguered

picture. It was certainly a commercial flop. Over 30

censorship cuts were made even before the film was

released, and this didn’t prevent some critics from

complaining about the harshness of what remained. “This

is the saga of a roughneck you wouldn’t put up in your

stable,” the Variety reviewer complained. “The

horses might complain. Spencer Tracy is cast in his most

distasteful role.” And in fact, Tracy’s character seems

almost benign alongside his neighbor, played by Marjorie

Rambeau, who shoots a would-be rapist and a police

snitch with the line, "This ain’t murder, this is just

house cleaning.” |

|

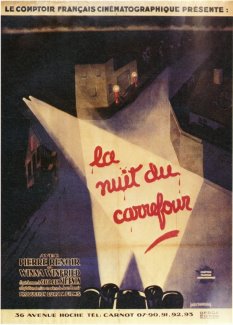

La nuit du carrefour.

To the best of my knowledge, Jean Renoir’s low-budget

adaptation of a Inspector Maigret mystery by Georges

Simenon—a novel available in English as

Maigret at the Crossroads--remains

so obscure outside of France that it’s never even been

subtitled in English, and you can’t (yet) even find it

on DVD there. But this highly atmospheric noir, set

around a garage in the grubbiest of Parisian suburbs, is

without a doubt the most erotic movie Renoir ever made,

thanks mainly to the Danish actress Winna Winifried, who

plays a major role as a druggy femme fatale named Else

Andersen (and who appeared in only half a dozen French

and English films after this one, all of them even more

obscure). Renoir’s brother Pierre plays Maigret, nearly

all of the action occurs at night, and part of what’s so

exciting about the film, in spite of its confusing plot

(apparently occasioned by one of the reels being lost),

is the use of direct sound, especially in conjuring up

an intricate sense of offscreen space. This was Renoir’s

second talkie feature after La Chienne, and

significantly the opening credits highlight the various

noises in a garage as if they were stretches of

musique concrète. Godard has celebrated

La nuit du carrefour

as Renoir’s most mysterious film, as well as the

greatest of all French police thrillers. |

|

|

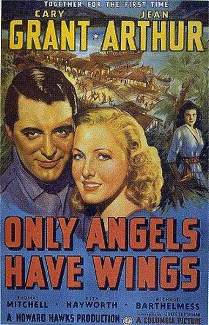

Only Angels Have Wings.

Honest and profound hokum may sound like a contradiction

in terms, but I can’t think of a better way to describe

Howard Hawks’ unlikely yet beautiful and thrilling

masterpiece (1939) about daredevil pilots in a remote

South American port who risk their lives delivering the

mail across a threatening mountain pass. The sense of

void and impending, meaningless death that surrounds and

encloses all the banter, braggadocio, and risk-taking

makes this seem like the most existential of Hawks’

adventures. Cary Grant--once described by Dave Kehr in

this film as “the high priest of some Sartrean

temple”--is the group’s fatherly boss, Thomas Mitchell

his best friend, Jean Arthur the showgirl who sticks

around because of her love-struck devotion, and Sig

Ruman plays Dutchy, the uncle type who runs the bar

connected to the small airport. The uncannily expressive

silent star Richard Barthelmess plays the returning

pilot who once caused the death of a copilot due to

cowardice, and Rita Hayworth plays his newlywed wife, an

old flame of Grant’s. The precise sense of ethics

governing all the interactions between this motley crew

is as striking as the artificiality of the settings.

|

|

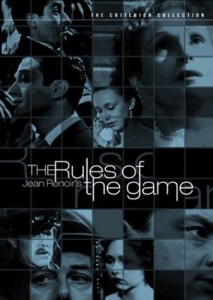

The Rules of the Game.

Virtually everyone agrees that this is Jean Renoir’s

supreme masterpiece, made and released the same year as

Only Angels Have Wings

and even more of a virtuoso ensemble work. Yet

this was so adroit in catching the troubled zeitgeist

of France at the time that it was loathed by audiences

at the time of its release, making it the biggest flop

of Renoir’s career. Only many years later, after it was

painstakingly restored and reconstructed, was its

greatness seen and acknowledged. Mostly set in a country

chateau over a single weekend, where the crisscrossing

romantic intrigues of both guests and servants play out

in intricate counterpoint, culminating in a costume

party, Renoir joins the proceedings as a major actor and

character as well as writer-director, attempting to

serve as go-between between two of his most intimate

friends, the wife (Nora Grégor) of the Jewish marquis

(Marcel Dalio) who’s hosting the weekend and the

lovesick but rejected famous pilot (Roland Toutain) who

wants to run away with her. As a view of French society

in 1939, this tragicomic farce is both scathingly

satirical and warmly compassionate, though it was

plainly only the scathing satire that most members of

the contemporary audience responded to.

|

|

|

Scarface.

My all-time favorite gangster film, put together like a

macabre black comedy that eventually veers into

something very close to Greek tragedy (complete with

brother-sister incest), Howard Hawks’ uncharacteristic

masterpiece beats out the

Godfather

features in at least one major respect: it is completely

unsentimental about both crime and violence. (Among the

half-dozen credited and uncredited hands who worked on

the brittle script are Ben Hecht, W.R. Burnett, and

Hawks himself.) The movie is in fact so blunt (Howard

Hughes, the producer, always had a taste for

scandalizing his audience) that it had endless battles

with censors, a few of which it lost, yet its anarchic

spirit shines through triumphantly in spite of

everything. (The only concession—a stupid dialogue scene

among Concerned Citizens—clearly belongs to a different

picture.) Paul Muni’s galvanic screen debut in the title

role, Tony Camonte, a lout with a distinct resemblance

to Al Capone, plays him like an innocent caveman, at

once charming and terrifying. And the secondary cast—Ann

Dvorak, Karen Morley, Boris Karloff, George Raft

(another memorable debut, featuring his signature

coin-flipping), Vince Burnett (as an illiterate

secretary who makes Tony Camonte seem like an

intellectual), Osgood Perkins (father of

Anthony)—bristles with uncommon, manic energy. Note:

every time some gets bumped off in this movie, which is

pretty often, an X appears somewhere on the screen, and

the placements of these markers are both ingenious and

unnerving. |

|

Story of the Late Chrysanthemums.

My favorite feature by the great Kenji Mizoguchi is

lamentably available at present only in French and

Spanish editions, as

Contes des chrysanthèmes tardifs

and

Historia del último crisantemo,

respectively -- a situation that’s bound to change

eventually, because I’m far from alone in my reverence

for this film, even in the English-speaking world.

Oddly enough, the tragic plot, set in the late 19th

century, is very close to that of a backstage musical

such as

There’s No Business Like Show

Business, at least in its initial

setup. The hero, the adopted, spoiled, arrogant,

sixth-generation heir of a famous and very successful

Kabuki actor in Tokyo, is still immature as a performer,

but the only one with the guts to tell him so to his

face is a family maid and wet nurse whom he immediately

falls in love with because of her honesty and sincerity.

(Miraculously, all this occurs during one virtuoso

lengthy take that accompanies the two of them walking

home from the theater, a shot in perpetual motion.) The

maid then gets fired by the hero’s wife, and when he

disobeys his father’s order to stop seeing her, he gets

banished as well. They leave for Osaka, where he

struggles for years as an actor with her support and

eventually joins a traveling company. When he’s

eventually invited to rejoin his father, he’s forced to

part company with his lover, whom he sees again only on

her deathbed, after he’s become famous and celebrated.

Part of what’s so remarkable about this film’s two-part

structure is the way Mizoguchi repeats the same camera

angles in scenes that occur years apart, in the same

settings, to stir our memories almost subliminally. |

|

|

Sylvia Scarlett.

For me, this bizarre and poetic 1935 feature that tanked

at the box office, is also in many ways the most

interesting and audacious movie George Cukor ever made.

Katharine Hepburn disguises herself as a boy to escape

from France to England with her crooked father (Edmund

Gwenn); they fall in with a group of traveling players,

including Cary Grant (at his most Cockney); the

ambiguous sexual feelings that Hepburn as a boy stirs in

both Grant and Brian Aherne (an aristocratic artist) are

part of what makes this film so subversive. Sudden

shifts in genre match the equally sudden shifts in

gender as the film disconcertingly changes tone every

few minutes, from farce to tragedy to romance to crime

thriller–-rather like some of the French New Wave films

(e.g.,

Breathless and

Shoot the Piano Player) that were

to come a quarter century later. Cukor’s usual

fascination with theater and the self-images of women,

assisted by his expert cast, somehow holds everything

together. The great English short story writer John

Collier collaborated on the script, and Joseph August

did the evocative cinematography. |

|

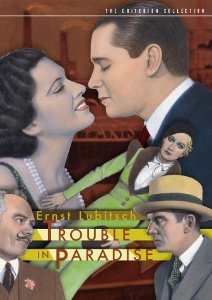

Trouble in Paradise.

By general agreement, this is Lubitsch’s most perfect

comedy, beautifully paced and acted and edited and

spoken, and it’s so graceful and seemingly effortless

that you can mainly only feel the Depression leaking

through the pauses and around the edges of the plot.

It’s also quite possibly Lubitsch’s most complex

picture, because, as in Renoir’s movies, every character

has his or her own reasons, and everyone invariably

knows and thinks more than he or she is saying. Herbert

Marshall and Miriam Hopkins are a couple of gifted

thieves and con artists who meet and fall in love in

Venice while attempting to fleece one another. After

they join forces, they go to work on an heiress who runs

a cosmetics factory in Paris (Kay Francis), with

Marshall serving as her secretary, but their prey seems

to know at times that she’s being robbed and doesn’t

exactly mind, and he’s more than a little ambivalent

about his work as well. The film also makes room for

Charles Ruggles and Edward Everett Horton as a couple of

romantic rivals and well-to-do stooges who are pursuing

the heiress as well; the screenplay is by Samson

Raphaelson and Grover Jones. |

|

|