|

|||||||||||

|

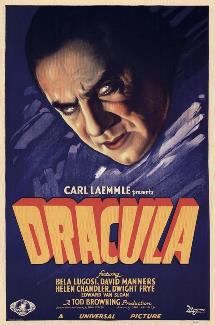

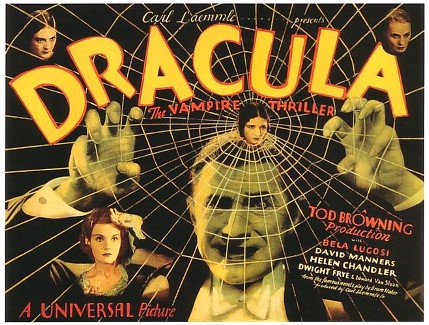

Dracula (1931), while perhaps seeming tame to modern audiences, launched the modern horror film as we know it. It was the first time in an American production that the supernatural really did exist, rather than being explained away. The film draws from the 1927 Broadway stage adaptation by Hamilton Deane and John Balderston more than the far superior original 1897 novel by Bram Stoker. In fact, the film was originally planned to be more faithful to the novel but financial constraints imposed by the Depression altered those arrangements. Most of Dracula looks like a filmed play, except for the opening eighteen minutes in Transylvania that were retained from an early script treatment by Louis Bromfield.

The plot has been re-envisioned many times. My synopsis refers only to this particular version: if you read the book, you will note many very marked differences. Real-estate agent Renfield travels to Transylvania in the Carpathian mountains so he can complete the sale of Carfax Abbey, a large, cavernous ruin of a property in England, to a certain Count Dracula. The locals are terrified when Renfield, en route, announces his destination, warning him that Dracula and his three wives are vampires. Renfield takes no notice and proceeds to the castle. After Dracula signs the deed for Carfax Abbey, he drugs Renfield’s wine and, shooing away his wraith-like wives, feeds on him (an image with suggested homoerotic subtext, surprising for the period). We next see the storm-tossed ship “Vesta” bringing Dracula, the now-deranged Renfield, and the coffins of earth in which Dracula must seclude himself during the daylight hours, to England. Shots of the crew and storm are stock footage from a silent film The Storm Breaker. The ship arrives in England deserted, the captain’s lifeless body tied to the ship’s wheel, and Renfield, the only living passenger, a raving madman who wants to consume small living things. Renfield is confined in the sanitarium of Dr. Seward whom Dracula seeks out and meets at the theatre along with his daughter Mina, her fiancé John Harker, and her friend Lucy Weston. Lucy is soon Dracula’s first victim in England, and Seward’s suspicions about her strange death as well as his bizarre patient Renfield, lead him to bring in his mentor Professor Abraham van Helsing, an authority on rare diseases and occult matters, to investigate. Dracula makes himself a charming guest in Seward’s home, and Mina is attacked in her sleep. Van Helsing realizes that Dracula is a vampire. It is a bit uncertain what Renfield does for Dracula: in the book, Dracula is a shadowy figure who needs a familiar to invite him into the homes of his victims, but here Dracula has ingratiated himself very nicely. Nonetheless, Renfield eventually verifies that Dracula is indeed the supernatural attacker of Lucy and Mina, and Dracula kills him. Van Helsing and Harker track Dracula to Carfax Abbey--next door apparently so it’s not very difficult, and destroy him by driving a stake through his heart. While much of the film has a certain slow quality, the iconic performance of Bela Lugosi as Dracula (an identification from which he was never to escape), as well as Dwight Frye’s Renfield and Edward van Sloan’s Van Helsing, are authoritative and without peer. The direction by the otherwise great Tod Browning is rather lackluster. During an interview with historian David J. Skal, David Manners (“John Harker”) reported that Browning was not even on the set for much of the filming, his job being performed by cinematographer Karl Freund. Nevertheless, this is a film of such historical importance that it belongs in every collection. In the early days of talking films, dubbing was nearly impossible with the crude sound techniques of the period; moreover, foreign-language audiences wanted to hear actors’ own voices on the screen, still very much a novelty. As a result, a number of Hollywood films were simultaneously shot with foreign casts. Most of these do not survive, but the Spanish Dracula does: a beautifully preserved negative was discovered in the late 1980s (with one reel sadly destroyed by nitrate decomposition). It is 30 minutes longer than its English-language counterpart, following the shooting script more closely; and, except for Lugosi’s, Frye’s, and Van Sloan’s absence, it is a far more inventive piece of film-making. The producer, Paul Kohner--husband-to-be of beautiful young Mexican leading lady Lupita Tovar--was determined that this version, made for a fraction of the main film’s cost, would be superior. It was shot at night, while the English-language Dracula was filmed on the same sets during the day. The fluid, often expressionist, use of camera movement and the more full-blooded approach do indeed make it superior to Browning’s version. One must note that Kohner was a friend and admirer of the great Nosferatu director F.W. Murnau, and some actual shots in the Spanish Dracula replicate those in the earlier film. One does miss Lugosi however.

Universal’s triple-dip Dracula--the new 2-DVD “75th Anniversary Edition”--is the studio’s reply to fans who had complained that the earlier transfer was too dark (1999 “Classic Monsters” edition, re-issued in the “Legacy Collection” of 2004). However, it is a very unsatisfactory reply. Some background: the original negative of _Dracula_ was over-printed in the 1940s and disintegrated, so copies must be made from later-generation elements like fine-grain positives and duplicate negatives, none in very good shape. Given the conditions of the materials thought to be available, no real restoration is ever going to be possible. That didn't deter Universal from using the same mediocre sources as before and raising the brightness level--and the sharpness to a lesser extent--for their "75th Anniversary Edition." The result is a glary, edgy picture in which the already high level of grain and serious print damage are so accentuated that the film is nearly unwatchable. Universal’s overly cautious anti-analog/anti-digital copy-protection makes matters worse: if one needs to play the signal through a VCR into a TV--and the VCR permits it, the glare, incessant grain, and damage become even more unbearable. Playing this Dracula directly into a monitor via component inputs yields results almost as unacceptable. Universal’s changes make it possible to see all the background details, but only because everything looks fluorescently lit; true focus is actually diminished amidst the glare and exaggerated print problems. A film which, more than almost any other, is about night and shadows, now has scant evidence of either, the added artificial brightness lending every detail equal weight and depriving the film of visual dimensionality. Most black levels are now more often gray, and whites can be overpowering; the effect is one of badly faded, deteriorated film stock. This was not the film-makers’ intent. One of the first remarks in the film, spoken fearfully as the carriage speeds toward the village near the end of the day, “we must reach the inn before sundown,” is now rendered ludicrous because it looks like noon in the desert. Dracula’s subterranean crypt now has a bright light source as does the carriage rendezvous at midnight; such brightened dark shots are especially undermined by the unremitting prominence of grain and damage artifacts.

For the first time on DVD, the sound has no erroneous omissions (the final VHS and the laser-disc were correct): the 1999 DVD accidentally erased the few seconds of Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony that conclude the theatre scene, while the 2004 “Legacy Collection” DVD omits the death screams of Renfield and Dracula--originally removed by censors, restored for laser-disc in the early 1990s, and included in the 1999 DVD. Unfortunately, the sound elements used here are the worst I have ever encountered--even compared with the most degraded TV prints: all dialogue is muffled, weak, and has a thick layer of buzzing distortion, many lines completely unintelligible; even viewers with normal hearing will need the English subtitles. Earlier DVDs had better sound (particularly the 1999 disc), and it is puzzling that Universal would judge the current sound elements to be acceptable. The primitive sound for Dracula was never good, and viewers have commented correctly that the audio in the 2004 “Legacy Collection” release was much inferior to the initial 1999 release. The sound in the current offering is similar to the 2004 edition but more intensely distorted. Why Universal didn’t reuse the far preferable sound track from the 1999 DVD for both later releases, simply reinstating the few erased notes at the end of the theatre scene, is a mystery. Universal has always been, and is still, confounded by the squarer, roughly 1.19:1 aspect ratio of early 1930s talkies. Criterion, on the other hand, dealt with the squarer frame elegantly in their 2004 restoration of Fritz Lang's M --also a 1931 film, preserving the original shape and the visual information by shrinking the image very slightly and pillarboxing it (the R2 Eureka transfer is similar, perhaps even more successful). The situation with Universal is a bit more complicated. The early sound films were filmed at full-frame 1.33:1 and exhibited in three ways: [1] synched with soundtracks recorded on discs (certainly a Herculean task given the technology of the period), [2] as silent films with inter-titles, and [3] with optical soundtracks--the way we know them. These seem to be the only elements to survive. Unfortunately, the optical sound tracks replace visual information in the 1.33:1 frame, throwing it off center and squaring its shape; in effect, the early Universal films, as they come down to us, have aspect ratios of about 1.19:1--ironically like the German expressionist films which were often their inspiration. Rather than shrink and pillarbox what remains, Universal has always enlarged the squarer viewing area to later Academy standard 1.33:1 (really 1.37:1) and cropped even more away from the frame at the edges. While that was already a poor solution, their current practices are more damaging and interventionist: shots are actually reframed, zoomed, and cropped to differing sizes at the discretion of the telecine engineer (usually losing more information than previously, owing to a preference for larger images)--in essence, making a pan-and-scan version of a non-widescreen film. The frame is occasionally shrunk as well as reframed to keep its contents intelligible: e.g., the newspaper clipping in Dracula, like the one in The Invisible Ray of “The Bela Lugosi Collection.” While a simple zoomed and cropped image already compromised the original appearance, the creation of continual new image sizes and placements is nearly a refilming: this Dracula goes farther than before in distorting the visual compositions of great cinematographer Karl Freund by inventing new relationships among shots. The wonderful Spanish Dracula, also in the current set, looked splendid before (except for the worn show print--the only extant copy--used as the replacement source for the missing reel); nevertheless, Universal has zoomed, cropped, shrunk, reframed, and panned/scanned it as well. Clearly, no film having an aspect ratio of 1.19:1 will ever be well-served by 1.33:1 zooming and cropping, but Universal’s intrusive new procedures retain even less of the original visual structure. Happily, not as much brightness is added to the Spanish Dracula because the original negative was already in such fine condition. I should mention that like the 2004 “Legacy” edition, there are no ordinary English subtitles for the Spanish Dracula, only subtitles for the hearing-impaired that include transliterations of sound effects and place sentences on the screen near whomever is speaking. Only the 1999 edition has the sort of English subtitles that one expects in foreign-language films. With all the visual rearranging, it is additionally frustrating that in some respects, this Spanish Dracula has a few more authentic elements than its DVD/VHS predecessors. According to leading authority David J. Skal, the original film has the same abbreviated stock “Swan Lake” title music that opens the Lugosi Dracula, Murders in the Rue Morgue, and The Mummy. But since the film never received copyright registration--and indeed, was long thought lost, Universal couldn’t copyright it in 1992 unless they made minor alterations to differentiate it from the public-domain original elements. So they substituted another performance of the title music which is slightly less truncated and continues into the first fifteen seconds of the film, dovetailing with the opening dialogue. Apparently, Universal has since worked out the problem because the original, shorter stock “Swan Lake” title music is heard in the “75th Anniversary” set, ending at the same point as in the Lugosi film. Interestingly, the first exterior long shot of the traveling coach used to be shorter. It is now extended by a few seconds--longer, in fact, than the analogous shot in the Lugosi film--even though the title music is now shorter; it has also been reframed to match the Lugosi version’s current composition (more intervention). One must assume that the shot in the previous edition was cut slightly to provide a logical point at which the substituted music could end. Again to differentiate their version copyrighted in 1992 from the public-domain original, Universal inserted a few notes of music (the opening phrase of the Schubert symphony heard in the theatre scene) at several points where Dracula rises from his coffin. In the new transfer, Universal dispenses with that added music (at 24:10-25 and 40:56-41:14). While the corrections are a plus for owning this edition, they do not offset the intrusive overall visual revamping of both films. Moreover, perhaps to provide an alternate means of “differentiation” for copyright purposes, the closing ballet of the theatre scene--shots from the 1925/29 Phantom of the Opera--now substitutes the same music (again, a snippet from Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony) performed more slowly, ending the scene with an entirely arbitrary, unmusical fade that is out-of-sync with the bowing dancers on the stage and undercutting any sense of closure. The set includes Kevin Brownlow’s good 1998 95-minute British documentary “Universal Horror” narrated by Kenneth Branagh (repeated in the “75th Anniversary Edition” of Frankenstein), with film clips in 4% PAL speed-up--very strange for those of us who have spent our lives with these famous films at the original theatrical speed and pitch reproduced in NTSC. Also, there is a terrible biography of Lugosi--“The Dark Prince”--that amounts to 36 minutes of 5-second interview bytes and film clips. Moreover, Universal conveniently omits the fact that it was their own studio which cashed in on Lugosi’s Dracula image in the 1930s--as it has ever since--and soon unceremoniously showed him the door, leaving the gifted actor unemployed and desperate. There’s also a new, ill-conceived, unappealing commentary track by Steve Haberman (who created the moronic parody Dracula: Dead and Loving It). The new “Monster Tracks” feature consists of commentary fragments in the form of optional subtitles; they are often too long to be read in the time allotted to them on the screen. Carried over from earlier editions, the other extras are excellent (except the optional Philip Glass film score): scholar David J. Skal’s brilliant, probing, enthusiastic commentary and his documentary “The Road to Dracula,” the re-release trailer (also unnecessarily brightened here), and a good poster/stills gallery. The “75th Anniversary Edition” Dracula is not a good replacement for previous editions of the Lugosi film. However, as some elements of the Spanish version are now more accurate, the reader may decide whether they compensate for the edition’s many other deficiencies. The 2004 “Legacy Collection” set, still very much in print (UPC 025192445521), is a better way to experience Lugosi’s Dracula on the whole; it comes with all the 1999 extras including the Spanish version (in its previous variant), as well as three Universal sequels, for the same price. The excellent 1999 single R1 disc containing English and Spanish Draculas and all the extras is long out of print, but third-party amazon.com sellers seem to offer it at very low prices. --Robert E. Seletsky ©2006 |

|||||||||||

|