Return

to DVDBeaver

|

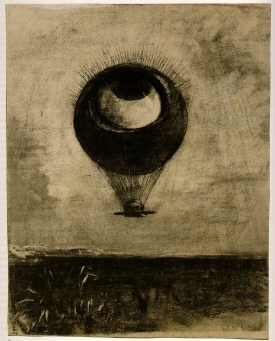

ODILON

REDON: THE EYE LIKE A

STRANGE BALLOON (1996)

Directed

by Guy Maddin

4

minutes and 31 seconds

16mm,

B&W (monochrome)

Available

on the DVD Short 2: Dreams (formerly Short Cinema Journal Vol.

2)

DVD

produced by Warner Brothers Ó

2000

Special

Features for Odilon Redon:

·

Production notes

·

Commentary by Guy Maddin

·

Storyboards (via alternate angle feature)

Reviewed

by Richard Malloy (aka “Al Brown”)

|

MoMA, NY (1878)

Commissioned by the BBC to create a short film inspired by

a favorite work of art, Canadian avant-garde filmmaker, Guy Maddin, selected The

Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity, a charcoal sketch by the

leading French Symbolist, Odilon Redon (1840-1916). Redon's piece was part of a

series of illustrations he created for Charles Baudelaire’s French

translations of the works of Edgar Allen Poe.

As Redon took a certain impressionistic distance from

Poe’s text, Maddin does likewise with Redon’s illustration. Though one shot is a direct cinematic rendering of the title

work, Maddin was not really interested in duplicating Redon’s drawings or

following the narrative of Poe’s text. Instead,

he sought to broadly emulate the black, smudgy texture of Redon’s charcoal,

which he describes as “oily as a train engine,” and took narrative

inspiration from the silent film, La Roue

(1922), by one of his favorite filmmakers, Abel Gance.

Whereas Gance’s epic originally ran a full 8 hours, the BBC limited

Maddin’s submission to “4 minutes, and not one frame more.”

Should you find the narrative a tad murky in sections, understand that a

rather significant amount of redaction was inevitable.

The story, though fairly simple and straightforward,

may well be lost to the casual viewer beneath the endlessly bizarre imagery and

intricately layered soundtrack. Like

Gance’s La Roue, it is a

love-triangle between a father, his son, and an orphan girl who joins them on

their great railway journey across the surreal landscape of life.

Each character is conveniently identified by name-tag: the father,

Keller, the son, Caellum, and the orphan girl, Bernice.

When we first meet K & C, they are happily riding the rails, a proud

father and his young, adoring son. Within

the first 60 seconds, we are witness to C’s sexual maturing, dramatized by the

flash of a beard sprouting across his face (spreading from one ear to the other

in time-lapse fashion) and his emergence from a giant boulder-like snail-shell

cladding his lower body. It cracks

open with an ominous explosion, and an adult actor emerges to take over the role

of C. K & C soon come upon the

comely Bernice, still clad in her juvenile shell.

B joins them on their journey and quickly becomes K’s favorite.

Soon, B’s shell also breaks away, she emerges into maturity, and the

inevitable sexual tension is born.

The rest I leave for you to decipher, though pay

particular attention to the jackhammer teeth-chattering, the image of the

double-blinded father, the son’s head hanging like plump fruit from a Dali-esque tree, and the eaten beard. This

film is a catalog of exquisitely rendered, dark dream imagery.

Maddin’s original cut ran 5-1/2 minutes and he

concedes that the 4 minute cut came at the expense of narrative clarity, such

that the images appear to be ‘dealt out like a pack of cards’.

As with an earlier experience of being asked to pad out a film to feature

length for exhibition (Tales from the

Gimli Hospital), the easy-going Maddin complied and, in both instances,

placed his stamp of approval upon the final cut (without stating a preference).

Although the film is timed at 5:11 on the packaging, it is, in fact,

precisely 4 minutes – plus about 30 seconds for the credits.

Regarding the quality of the transfer, it is

difficult to tell whether a particular hazy, murky or otherwise distressed image

is Maddin’s doing or otherwise. From

the high quality of the other, more conventionally shot films in this collection

and the lack of any pixelation or other obvious digititis, it seems safe to

pronounce it a very good, if not excellent transfer.

Worth mentioning, however, is a peculiar, tiny, white silhouette of a

camera superimposed like a TV network logo in the upper part of the screen just

right of center. It appears to have

been added after-the-fact and remains totally unexplained.

Though present throughout, it quickly recedes from prominence amid the

busy mise-en-scene and is not overly

distracting.

The film features Maddin’s typical, densely-layered

scoundscape, replete with hissing, steam-spewing clamshells, the incessant chu-chu-chu-ing

of the train and tacka-tacka-tacka

of the rails, the intermittent sounds of teeth being brushed and great waves

crashing against rocky shores, and a single line of dialog: “Oh

the humanity!” Judging sound

quality is hindered for the same reasons as the video, but by reference to other

films on this disc, one may presume that it is an accurate reflection of the

original mix. As with all the

commentary tracks accompanying the various short films on this disc, Maddin’s

sounds, quite literally, phoned-in. But

he provides an insightful and nuanced commentary in his typically engaging

style, detailing just the sort of information a curious viewer would be

interested in knowing. Brief but

informative production notes are included, as well as an alternate angle feature

displaying Maddin’s rudimentarily drawn storyboards.

A Note to the Perplexed: One

might be inclined to wonder why anyone other than a bona fide Guy Maddin fanatic

would be moved to purchase a DVD for a single, four minute film, regardless of

how interesting or innovative it may be. Certainly,

one would not likely be so moved even at its relatively inexpensive price of

$10-12. But in addition to Maddin’s

film and a veritable trove of wonderful short features (including Bride

of Resistor, Depth Solitude, A Guy Walks Into a Bar and the original short

version of Big Brass Ring), there is

also Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962),

the 30-minute science fiction classic that inspired Terry Gilliam’s 12

Monkeys. Marker’s film is one of the true landmarks in the history of

cinema and something no sci-fi aficionado or lover of experimental cinema should

be without. So why not review La

Jetée, you ask? Simply because

it’s a film that’s received so much critical recognition and appreciation

over the years that any review I could muster would be completely superfluous.

Suffice to say that it is fascinating, mesmerizing, thought-provoking and

– for one brief moment – utterly transcendent.

Awards: Best Canadian Short Film - Special Jury Citation,

1995 Toronto International Film Festival

Odilon Redon mini-bio CLICK

HERE

Abel Gance’s La

Roue CLICK

HERE

Review of Guy Maddin's Careful (1992) CLICK

HERE

Return

to DVDBeaver