![]()

![]()

|

by Fred Patton |

|

Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1964 Red Desert has invited an array of critical reactions, such as its classification as an exhibition in the boring and the bleak, as well as its estimation as a thoughtful mood piece, and also its recognition on the level of masterpiece. As a rich, multi-layered work, the film readily accommodates a wide categorical continuum. Upon objective examination of Red Desert on an operational level—the story and the film technique that conveys it—the formal cues for addressing the functional level become apparent. In fact, meta-narrative cues will be found to emerge from inside the narrative as well, as Giuliana discusses the effects of color and sound. The sketchy back story of Red Desert involves the protagonist, Giuliana, who has had a stay of unspecified length in some sort of mental hospital for some form of nervous breakdown after suffering shock from an otherwise minor car mishap purported to be an accident. While physically fine, Giuliana has found herself estranged from everyone and everything, particularly her own husband who has not understood and has not been there for her. |

|

|

The plot unfolds with a disoriented Giuliana bringing her young son, Valerio, to the plant where her husband works. Here she meets an important business associate of her husband, named Corrado. The way he looks at her uncomfortably disarms her—evidently she has not been looked at this fashion for some time. The possibility of connecting with someone begins to give hope to her desperate crisis. Her son and Corrado constitute the only real prospects in this regard, as the doctors have tasked her to love someone or something in order to reintegrate herself into a mentally healthy life. Corrado comes closest to understanding and connecting with Giuliana on some level, given his own existential issues, but for this very reason, the pre-requisite of emerging from such a depth of self-absorption presents a questionable prospect. On a sufficient level of abstraction, Red Desert constitutes a narrative meditation in mise-en-scène and sound on the subject on alienation in the face of changing times and technology. The operation of mise-en-scène and sound in conjunction with narrative exposes the formal cues necessary to approach the work on a functional level. Despite the film’s remarkable visual strength, the more modest auditory cues perhaps provide the strongest functional indicators. The soundscape of Red Desert borrows from two genres—thriller and sci-fi—employing eerie and suspenseful sound tropes reminiscent of classical thrillers as well as outer-space sound effects in addition to the undercurrent of industrial noise. For a modernist work, this borrowing out of context foreshadows post-modern developments, situating it more as a late modernist work. The fact that Red Desert, a drama, is stylized by the sonic staples of genres it does not conform to in regards to content, provides a subtle cue to reassess the manner in which story and plot function. The thriller aspects can be seen functioning within the plotline of Giuliana trying to cope in the aftermath of nervous breakdown. The sci-fi element can be seen in the exploration of the resulting dislocation. |

|

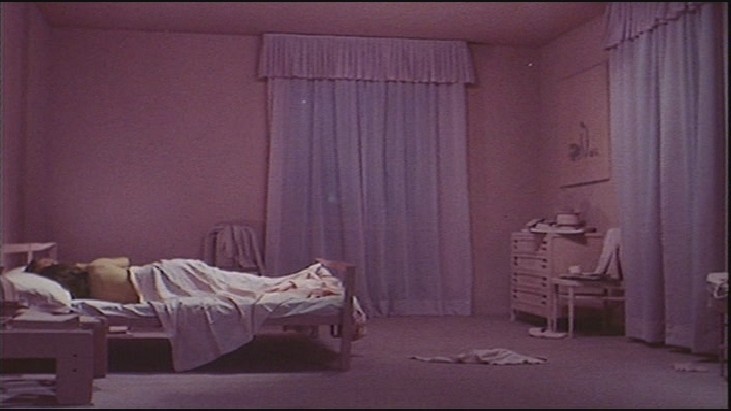

| In considering mise-en-scène, principally composition and the use of focus and color, more functional cues emerge that increasingly suggest the film’s underlying formal unity. Antonioni sought to paint a film, more than write it, and indeed it is a film of picturesque framings and evocative moods. The extensive use of doorways and passageways call attention to the operation of framing, and the manner in which a character may come into or out of frame. The long takes tend to hold both the moment before and after the character has entered the frame, suggesting impermanence and the independent, though vulnerable, existence of the landscape. Furthermore, the framing can become very restrictive, such as slowly exposing Giuliana’s small empty shop through ten distinct shots, where the space is only very gradually revealed. This creates a very fragmented perceptual experience corresponding to Giuliana’s own state. Each shot affords a precise framing for artistic composition, with swatches of color augmenting the effect. For meta-narrative touch, Giuliana remarks, “They are neutral colors that shouldn’t disturb.” |

|

In lieu of much depth-of-field, Antonioni opts to control exactly what is in and out of focus in a given shot, making a myriad of unusual, unconventional choices that suggest an underlying thematic statement. This strategy runs throughout the film, commencing with out-of-focus shots of an industrial work site as the opening credits flow. While we never see Giuliana out of focus, we often see surrounding people and things in a blur, with Giuliana occasionally popping into frame in focus, establishing a thematic tie with the alienated Giuliana’s POV. The use of color is the most dazzling aspect of Red Desert, which on a purest level, is visual spectacle. There is one sequence of natural color in the film, a brief story sequence related by Giuliana to Valerio. Everywhere else, color is meticulously calculated and arranged, with dynamic colorization correlating with Giuliana’s emotional states. |

|

|

Whether it’s painting in gray the grass and ground or a fruit vendor and his cart, or after some love-making, a nice touch of pink, color is constantly on the move. Whether the action is taking place within the factory, in the town, in the home or outdoors, there is a unified look, turning everything into an interesting piece of modern art. How reminiscent the factory and Giuliana’s house appear. The paintings in Giuliana’s home help key this modern art motif, as well as the housewife opening the curtains in her home to reveal the domestic décor’s complement to the scenery outside—the play of the real flowers on the living room table with the pinkish painted flowers on the wall juxtaposed with the pink-colored building outside. |

| A striking image of Giuliana and Valerio in their colorful coats in contrast to the drab gray of both the outdoors and the soldiers in uniform makes one think of a similar, though contextually much more powerful scene given its context in Schindler’s List where the little girl in the red coat contrasts with the surrounding gray of the Jewish ghetto. |

|

|

| It should be said that these colorful compositions don’t depict the ugliness of any of the locales and objects, and therefore don’t yield a simple condemnation of modernity and industrial advancement. These subjects are re-invented through these depictions, taking on new modes of beauty. In fact, beauty is revealed in a myriad of modern modalities. At the same time, humankind’s role as being engulfed in its technology, such as evidenced by Ugo and Corrado in the plant during the steam incident, or the man in the giant antenna, is quite suggestive. As for the latter example, the man is shown in conformance with the “other” beams in two aspects: 1) visually, given his complementary angular stance; 2) on the function of support, the beams provide structural support, and the man, maintenance support. On a similar note as the relationship between humankind and technology, even the logic of one plus one equals two is challenged with a lab scene with the young Valerio determines that one drop plus another drop equals one drop. Will logic always prevail? |

|

|

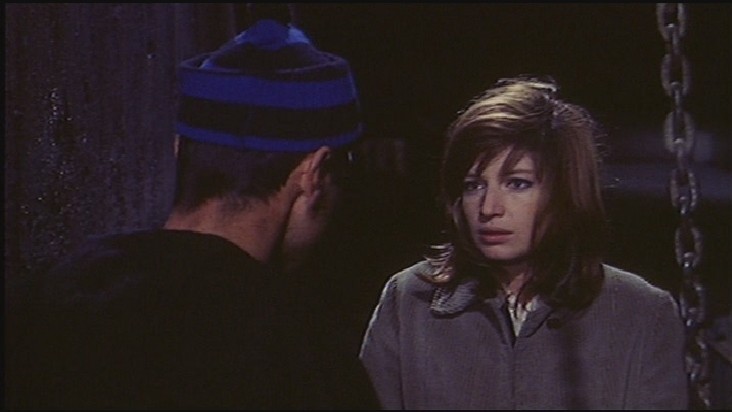

| The love triangle aspect of Red Desert exposes an interesting narrative tact. Giuliana and Corrado go to recruit an engineer for the factory, but he is not home. They are greeted by his wife, who gives Giuliana a few odd glances. They are allowed in to wait. With the wife off to retrieve something, Giuliana tells Corrado a veiled confession about “a girl” in the mental hospital. Corrado becomes someone she can confide in, in lieu of her unreceptive husband. The mystery of the reluctantly cordial housewife only becomes fully understood after the following scene when they track down her husband, and it becomes understood that she had recognized Giuliana from the hospital and found it inappropriate for her to be with Corrado. The cut directly after she rhetorically refers to Corrado’s wife is effective. Soon after being turned down by Mario, the husband, and after Corrado makes a small challenge about Giuliana not having said she knew Mario and asks who he is to her, we cut to an outdoor scene with Corrado alone, looking out into polluted water. It is a mild surprise when he turns away, and addressing someone as he walks toward them, it is Ugo, the husband, standing apart and alone as well, and faced in the other direction. In responding to Corrado’s address, he is answered by Giuliana who completes the literal physical triangle, standing alone, faced outward as well. This scene, which works on a multiple levels, perfectly counters the previous scene, re-instating Ugo in the picture. |

|

|

|

The presence of boats pervade the film, such as the mysterious boat harboring sickness, the industrial liner where Giuliana has a key discussion with Corrado, the mysterious boat that comes and goes in Giuliana’s beach story, and lastly, the docked boat where Giuliana has a discussion with the Turkish sailor. This significant conversation where neither speaks each other’s language yields for Giuliana perhaps the least vacuous conversation. This is where she comes closest to clarity for herself, voicing some realizations, as well as making a resolve to “stay.” A remarkable scene within the context of the movie, and says lot about the theme of communication that runs through the movie. |

|

|

The beach story Giuliana tells to Valerio is a significant inclusion in the narrative. Besides the striking visual differences from the rest of the movie, we contrast the not depicted girl from hospital with this adolescent in idyllic surroundings. The latter has found this isolated beach that serves as a refuge from grownups whom both bore and scare her (and growing up by extension), as well as boys who pretend to be grownup. Giuliana narrates “and there was no sound,” even as the natural sounds are there, just not the disturbing sound that has characterized the entire film. For all the beauty in the scene, the serenity breaks. First, there’s the disruption of the mysterious boat, “one of those that braved the seas and storms of this world.—And, who knows… of other worlds.” Next, a peculiar song arises, for the second time in the movie. This first time, was at the opening of the movie. The song in both cases makes the same progression, moving between loneliness, tension, calm and sweetness. The girl asks in the story, “Who was singing?” Giuliana answers, “Everybody. Everything.” Considering the story with the other girl, tasked to love someone, something, but not everybody, everything indiscriminately, the nature of the singing, whether heard at the beach or at the factory site, represents an overall awareness, longing, empathy, and vision that can overwhelm both in its intensity and the impossibility of sustaining it. The camera adapts the same rhythm with respect to pans and cuts in both scenes, unifying the much different factory sequence with the beach sequence. The beach has changed for the girl, inevitably it is not a place she can stay. The singing—the inner voice—will persist. |

|

|

| At last, and she stands once again with Valerio roughly where we found them at the beginning of the movie, the insight about the birds and the poisonous, yellow smoke imply Giuliana has new insight into how she may begin to adapt. |

![]()

![]()

Recommended Books on Italian Cinema (CLICK COVERS or TITLES for more information)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Italian Cinema: From Neorealism to the Present by Peter E. Bondanella |

Fellini on Fellini by Federico Fellini, Isabel Quigley |

Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism by Millicent Marcus |

Vittorio De Sica: Contemporary Perspectives (Toronto

Italian Studies) by Howard Curle, Stephen Snyder |

Italian Film (National Film Traditions) by Marcia Landy, David Desser |

Italian Movie Goddesses: Over 80 of the Greatest

Women in Italian Cinema by Stefano Masi, Enrico Lancia |

Italian Cinema by Maggie Gunsberg |

I, Fellini by Charlotte Chandler, Billy Wilder |

Vittorio De Sica: Director, Actor, Screenwriter by Bert Cardullo |