![]()

![]()

|

A Review by Fred Patton |

|

Playful, somber, resonant, Glass Tears displays much originality and deftness. As the debut, feature-length film of director Lai Miu-suet, also known as Carol Lai, Glass Tears takes incessantly sensationalized subject matter and crafts a work of understated beauty. Never slipping into melodrama or market-titillating exploitation, it effects a fluid balancing act between comic and dramatic moods while offering a thoughtful view of urban, Hong Kong hosted adolescence. The art direction of Poon Yik-sum along with the cinematography of T.L. Cheung provides a diverse color fest of meticulously arranged hues. Complementing this rich visual palette is Oakey’s distinctive soundtrack, providing shifting moods and thematic cues. The script, co-written by the director and Lui Hok Cheung, provide the subtle, vertical framework from which the film takes off. It’s no wonder the work made a fine splash at the Directors Fortnight at Cannes 2001. |

|

|

The story of Glass Tears involves the

search for a missing teen, Cho (played by newcomer Zeny Kwok), by her

grandfather Wu (the late Lo Lieh, aka Lo Lit), a retired Mainland

policeman, who ends up tracking down her friends and entering her

world. In the course of this, he meets P, her best friend, who turns

out to be a lot like he was, and together with her boyfriend Tofu

(Chui Tien-You) they carry on the semblance of investigation. Despite

his bad Cantonese, their differing lifestyles, and the wide age gap,

they forge some understanding.

A little time spent with Cho’s parents, Wu’s daughter (Carrie Ng) and her husband (Tats Lau), provide some insight into why Cho would run away. Despite the brief time allotted for characterization, Cho’s parents are far from one dimensional characters. While there are problems in the home, sensationalism is avoided. By subduing the dramatization of Cho’s parents troubled relationship, symptomatic sensationalism is traded for the characterization of the collapse. The small, deceptively minor details are brought to the foreground, revealing how realistic, how unfortunately everyday such an event is-how matter-of-fact it may play out. Tragedy is not shown as extreme circumstances, but extremely small details, gestures, sentiments that build up and effect ruin. This film does a nice job suggesting this. Violent events, whether physical or psychological, are shot with the key action scarcely entering the frame, thereby de-emphasizing the over privileged action in favor of psychological repercussion of it. The film is able to reverberate to a remarkable degree, effortlessly sustaining multiple viewings. Its payoff does not come in the currency of plot points, the play of characters within a scene, but rather, through the dramatic emphasis on accumulated interrelations of situational events, the way characters seems as much to be interacting with other characters at other moments, even themselves at other moments. A given situation itself benefits from characterization, yielding a certain spirit or over-voice. This accounts for a strong humanizing effect as the wider context is brought to the foreground. By fragmentation and reordering, conventional narrative is transformed into the poetic-not to capture or hijack attention, but to give it back to itself, to turn it loose, away from the narrowing effect of plot-level focus. In examining the manner in which events unfold in Glass Tears, it can be seen that a conventional approach to dramatization, heightening tension if not suspense as the dramatic action reaches toward completion within the scene, is not employed. The conventional unfolding is frustrated by forward jump cuts that hand over the typically more hard-earned payoffs quite easily. Only then might the scene return to where it had been interrupted. And only then does the true emphasis of the scene come to the foreground, a larger, more abstract context, now de-situated from the dominant force of familiarity. |

|

|

Lai, by breaking components of an event from their temporal and spatial moorings, brings selected interrelations to the foreground. This act of de-contextualizing events from a normalcy so strongly familiar that it lulls critical receptivity enables fresh looks to re-treaded themes. Temporal and spatial fragmentation is often driven by examinations of identity, especially with Hong Kong cinema. Mainland-Hong Kong issues run throughout, including the interchange of Cantonese and Mandarin, though Glass Tears is not primarily concerned with identity. A prevailing sense of confinement and stricture is evoked with an abundance of cell-like bars and grids, set against the freedom signified by the sea that separates Hong Kong from everything else, even as foreign products and people flow in. At the same time, Lai’s portrait of Hong Kong maintains hope and affection. |

|

Given the lack of depth-of-field shots,

attention is coerced to discrete regions of interest. Similarly, by

withholding introductory establishing shots, isolated fragments are only

brought together after exploiting their local subject matter. The

narrative is advanced by conceptual sequencing, such that the scene

details are provided as they are needed to establish formal relationships

extending beyond the event taking place.

Glass Tears reveals a bit of its subversive shot etiquette with its very first shot transition. In the frame, a woman is seated at dinner, her back against a wall. As she eats, she recounts a bit of her day, even laughing to herself at one point. While never making eye-contact with the camera, she remains front-and-center to it. The next cut reveals she’s actually having dinner with her husband, each of them virtually in their own world. Her husband sits diagonally from her such that as they each face straight ahead, they evade each other’s line of sight. The result of these two shots captures the rift between them and sets a tone of forceful understatement, while introducing the recurring theme of money. |

|

| The blending of Lai’s flashback orientation and the fast editing of Danny Pang, offers a dynamic editorial tandem. The early shot sequence where P calls Cho’s cell phone is a telling example of the film’s editorial M.O. Privileging relational dynamics over the unfolding of distinct incidents, the building of tension is not concentrated on the causal completion of actions, but rather, in the wider context in which the actions and the characters come into relational coherence. Formally, these relations are drawn through symmetry (i.e. inversion, compliment, mirroring) and isomorphism (similarity, repetition, echo). This shot sequence, which lasts roughly 24 seconds, begins with a close-up on a drawer just before a phone can be heard ringing from inside it. |  |

| [1] The wife opens the

drawer, countered fluidly by a match cut of the contrary motion of P

hanging up the receiver to yield a symmetrical transition. Just as P hangs

up the phone, the wife picks up the cell phone that was in the drawer [3],

in symmetric transition from 2. The moment the wife answers the phone, P

releases her hand from the receiver [4], once again a crisp symmetrical

transition providing contrary dynamics.

[5] Continuing the action of 4, the camera tilts up from the phone to [6] P’s face looking down at it. Match cut to Wu’s face also looking downward [7] in similarity to 6. Picking up the action of 7, the camera tilts down to the photo of P and Cho that decorates the case that Wu is observing in a nearby drawer [8]. This tilt mirrors the reverse tilt of 5. [9] Wu picks up the photo complementing 4 where P releases the receiver. Match cut from Wu’s motion of lifting the receiver to the contrary motion of the wife lowering the phone [10] in symmetrical transition, while resolving by reversal her earlier action, 3, of picking up the phone. Advancing the action of 10, the wife lowers her head [11], from which the motion flows into a symmetrical transition to P advancing on Little Mommy [12], who duplicates the wife’s posture of lowered head and distant gaze. |

|

|

| Even a beautiful, outdoor area is part of the symbolized sense of stricture, and it is not just the troubled youth, whom feel trapped, restrained, or confined. It’s a clearly a deliberate choice to emphasize the bars, which dominate the foreground. |

|

|

| The out-of-focus wall in the back ground gives the impression of the bars of a cell, as if a prison visit were taking place. |

|

| The old Mainland tiger is caged, along with his adopted cub, for whom Wu serves as a big brother figure. Family structure is contrasted by affluent and less affluent homes, as well as a substitutional family. |

|

|

|

Hong Kong appears under house arrest. |

|

A sense of restlessness is aggravated by a tropical scene pictured prominently on the wall. Even the bad guys are humanized by revealing the larger forces at work. After acting out, this young man will be seen nervously tapping his foot while sipping his drink and smoking his cigarette, all the while dominated by restlessness. A marvelous shot-the grids showing from under water, as well as above where P sits, her blouse looking like a brick wall and a ring of bars running underneath her as it circles the pool. The symbolic thrust is that she’s reading her favorite book that consists of maps of Hong Kong, here depicting Hong Kong’s 58 beaches, which she’s fixated on, while she not even knowing how to swim. |

|

|

|

| Here the pen knife reveals its symbolic duality: violent potential, even to oneself, as well as a cutting instrument, such as to cut through a fence such as to escape confinement. |

|

|

| There is a welcome openness in this film, a spiritedness marked by insight and compassion for the passionscape it visits. There is something that conscientious filmmakers always take into account-the place left behind, insomuch as it is remotely realistic, remains never quite situated or placed decisively, but stealing from and stolen by so many varied localities. Place is always on the move, its physical bearing arbitrary yet inescapable. |

|

|

|

THE DVD

|

|

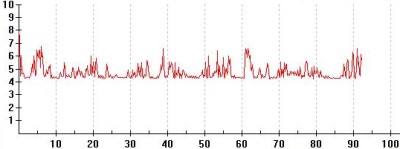

Glass tears is shot in 35mm, though Mei Ah’s DVD transfer is quite pedestrian. Given the color intensive cinematography, a better transfer would be most welcome, but in the meantime, this budget-oriented release is highly recommended. The DVD is region-0 NTSC with a 1.85:1 aspect ratio. Audio tracks in Dolby Digital 5.1 Stereo Surround Sound are provided for Cantonese and Mandarin, with subtitles in simple Chinese, traditional Chinese and English. The subtitles are passable, suffering mainly from grammatical errors for English. The running time on the case listed at 112 minutes is in accurate, as it includes the extras. The actual running time is 92 minutes and 36 seconds. The extras consist of two short interviews with director, Lai Miu-suet, and cast member, Zeny Kwok (who plays P), as well some making of footage and Cannes excerpts. |