![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

|

|

|

Man has a single choice; to think or not, and that is the gauge of his virtue"

One of the more misunderstood and unjustly maligned films in Hollywood history; King Vidor's 1949 thematically authoritative "The Fountainhead" was unable to shift many perceptions and find acceptance for its "expressionist fable" qualities. This derivation from usual Hollywood fare of the 40's required a much higher level of suspension of disbelief, one that the audience of the day were unwilling to respond with. It reached top spots on many of the worst film lists of that year with novelist and screenwriter Ayn Rand's deep and unbound dialogue helping to vault her philosophy known as 'Objectivism' (a cerebral anthem for day-to-day existence) into the more mainstream public eye. Intellectuals of the day expectantly applauded it, the bulk of society dismissed its melodrama and misunderstood its profound messages.

Ironically the very core fundamentals of the The Fountainhead deny public conformist reaction; that which would determine its box-office success or failure. To have had financial success would have meant either it had succumbed to the will and desire of the masses that it staunchly opposed OR that it had achieved an impossibly idealistic goal of altering society's entrenched perceptions. Instead though it failed the studio financially thereby adhering to the principles of its premise. Ironic indeed, and a strange gamble for Warner Brothers to take especially if they thought Rand would allow her scintillating discourse to be "dumbed-down" to appeal to a larger slice of the box-office gate. They were obviously attempting to capitalize on the popularity of her best-selling novel and spared little expense in production.

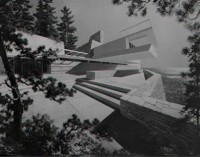

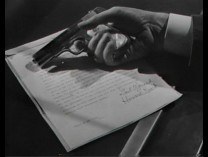

The film focuses on the uncompromising and dogmatic philosophical stance of the protagonist, architect Howard Roark - played by a strong, impassive and abruptly stoic Gary Cooper. He, in defense of artistic integrity and individualism, blows up a partially constructed building site, called Cortlandt Homes, manipulated from his own original design. The film introduces us to him, his philosophy, his actions, and finally the defense of the unwavering principles that he lives by.

The climax of the film is his court case. At his trial he soliloquizes about the formulaic adjustment of a creator's vision to adhere to popular opinion. He explains how this prevalent truism is as damning as the destruction of expression and individuality simply made in an effort to bow to the blind adherence and whims of the conformist mob. Using evolutionary man's discovery of fire, he argues that without allowing complete freedom of expression nothing of any value or substance would ever have been, or will be, created.

Hinting into Roark's lifestyle foundations are Rand's Objectivism principles of self-interest. The concept of selfishness as a virtue remains a difficult sell to her audience. As the film progresses we see the complete denial of altruistic values. Roark expounds "I don't ask for help, or do I give it". In his speech to parasite architect Peter Keating prior to clandestinely accepting to design Cortlandt, Roark states "A man who works for others without payment is a slave. I do not believe slavery is noble... not in any form, or for any purpose whatsoever." This validates his reason for rejecting to design Cortlandt on the sole basis of humanitarianism - to help shelter the masses. This harkens straight to the core of Rand's novel by stating that the creative 'self' is more important than the denial of 'self' for the sake of others. Roark states before his trial, "I'm selfish? - is that what they say? It's true I live for the judgment of my own mind and for my own sake". Rand's concept of man is as a completely heroic figure (in Roark's case as a psychologically isolated hero), with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive accomplishments as his noblest activity, and 'reason' as his only judgmental divining-rod. Perhaps idealistic, but ultimately appealing to U.S. audiences as Roark's speech links it to the very core of capitalistic and democratic flag waving values. This is the reason for the success of her book and my feeling is that it was far too unconventional for modern film as its vehicle of expression. The final result is the ethos of an "Art" film entangled within a perceived lecturing melodrama. The Fountainhead and its complete character focus deviates drastically from the standard cinema of the day with its more obvious definability and structure.

The film expression that I was initially drawn to the resolute "integrity of the artist" stance of Roark. I found this quite in common with the writings of Russian master filmmaker "Andrei Tarkovsky" as stated in his book "Sculpting in Time". This stalwart lack of capitulation to bend to the desires of the masses is exceedingly noble - in some minds bordering upon martyrdom when financial gains are the rejected reward. Ayn Rand evolved to be the mostly widely read philosopher of the 20th century. She (originally Alice Rosenbaum) is also of Soviet origins with St. Petersburg, Russia as her birthplace. An interesting co-incidence to Tarkovsky that doesn't escape me. Perhaps those bred in a more repressed culture are more apt to find obvious flaws and the means of identifying and coping with them in a more autarchic system.

Quite amusingly, The Fountainhead is filled with sexual and erotic symbols and motifs. I found these quite out-of-place for the times. Large office towers representative of phallic metaphors with a stunning 22-year-old Patricia Neal playing ice princess Dominque Francon. Jack Warner considered and then rejected Bette Davis, Ida Lupino and Barbara Stanwyck for the coveted role. Neal's Dominique sizzles as a tempest pot of strong-willed feminine sexuality. Initially she is marked as a domineering woman (her first name is no coincidence), complete with riding crop which she slashes across Roark's face to encourage his aggressive sexual conquest of her. She eventually acquiesces into a submissive and pouting lover... the passive love slave of Howard Roark, bowing to the strength of his "edifice". Cleverly imbedded, this symbolism is generally oblivious to most. Even when Dominique first spots Roark and his sinewy forearm muscles pumping the drill into the marble at her fathers granite quarry we rarely think twice about the scenes hidden implication.

Rand's book "The Fountainhead" (actually all her novels) expresses an extremely machismo archetype structure where male physical conquest of females are a prelude to desire and true love. Dominique is self-described as a character "with strength but not courage". She believes in Roark's philosophy, as does her husband of convenience and Roark's friend, newspaper magnate Gail Wynand (played by Raymond Massey). His one-sided adoration of her and her openly loveless expression to him are pragmatic if in total denial by all concerned. They do share one resolute bond though; a lack of courage to follow the trail which Roark is quietly marching ahead of them.

Comparisons to Wynand as media mogul William Randolph Hearst and Roark to master architect Frank Lloyd Wright seem too obvious, but the true champion of the film is Rand's wonderfully parable-infused dialogue. It is the blatant separation of this film to anything of a comparable nature, before or since. Each sentence harkens directly to a more universal meaning while not simply filling in the plot with expected conventions and expressions. We also see instances where Rand is furtively playing with words. As Dominique stares down into the granite quarry to the laboring Roark she states "Why are you looking at me?" Roark replies with a smile: "For the same reason you're looking at me!". Her coquettish attempts at teasing are easily discernable by the taciturn Roark. She later advises him to stop ogling her as it may be misinterpreted. His flat response; "I don't think so Miss Francon".

The Fountainhead has been aptly described as post-German expressionism from director Vidor with its fabulous model set designs of buildings. Cinematographer Robert Burks' low to medium camera angles reflect Roark adeptly as the strong-willed 'everyman' who battles the persistent seductions and temptations that cross his path. The camera lingers consistently on Patricia Neal as a beacon of sexuality. The shots taken below her show her dominance and in the final scene have her rising in the outdoor construction elevator to meet Roark as he majestically stands atop the tallest building in the world. Casting is perfect for Neal and this should have been her springboard to superstardom had the film garnered its anticipated box-office return. In my minds eye I see Henry Fonda as a more powerful and contemplative Howard Roark than Cooper portrayed but perhaps I am being too picky - Cooper made the role his own as he always seems to have done throughout his career.

What we are left with is a sterling example of Hollywood attempting to deviate and grow with expressionism centralized within a compelling plot of an uncompromising genius who copes and succeeds. The film's edict remains timeless but certainly more appropriate for modern 'art' film buffs with dialogue as its nerve-center and consistent and even pacing as its foundation. Although Hollywood is finally breaking new ground it doesn't make films like this anymore... and aside from The Fountainhead, truly never did. Gary W. Tooze |

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()