![]()

![]()

|

by Henrik Sylow |

|

|

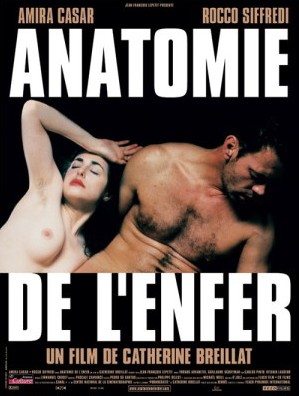

With a deep pulsating techno rhythm, Anatomie de l’enfer (Anatomy of Hell, 2004), Catherine Breillat’s latest film, opens with close-up of a young man slowly sucking a cock among trashcans in a back alley. Unimaginable a few years ago, films like Breillat’s own Romance X, Virginie Despentes’s Baise-moi (Fuck Me, 2000), and Gaspar Noë’s Irréversible (2003) no longer merely “suggest” sexuality. Even American cinema has caught onto the trend, as Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny (2003) shows. But whereas Noë and Gallo only provoke for the sake of titillation, whereas Baise-moi is little less than bad porn, Breillat treats sexuality with the same respect that she does any other human trait. For her, human sexuality is as normal as the next thing, so why not depict it? Based on her own novel, Pornocratie, Breillat made this, her tenth film—le film X—her most ambitious presentation of human sexuality to date, or should I say presentation of the “deconstruction of psychosexuality?” Breillat never depicts sexuality in an arousing pornographic sense, but in an almost Lacanian way. To Breillat, the images and the words are important, so important in fact that she ended her introduction of the world premiere with the following advice—or was it a request?: “You are about to see images which will shock you, offend you, and even repulse you. Please don’t laugh or boo. Please just observe the film in silence.” Originally, Breillat wanted to adapt Marguerite Duras’s La Maladie de la Mort (The Malady of Death, 1983) for the screen, but she was refused the rights. Disappointed and angry over the X rating of Despentes’s Baise-moi, Breillat reacted by writing Pornocratie. In many ways the story is an allusion to La Maladie de la Mort: A man hires a woman to spend several nights with him. On the last night he asks her if she believes that anyone could ever love him, to which she answers no. The next morning she is gone. |

|

|

In Anatomie de l’enfer, a woman, attracted to a gay man but rejected by him, attempts suicide by cutting her wrist with a razor blade, but the gay man walks in on her and saves her. After walking her home, he allows her to give him a blowjob, but is repulsed. “I want you to come and look at me from the angle from which I should never be viewed,” she says. “It will cost you,” he says. “I'll pay you,” she responds. Over the following four nights, the man visits her in her sparsely decorated house at the sea, where he is exposed to revolting images and aspects of the female sex. These intrigue him to such a degree that he ultimately has sex with her. Full of conflicting emotions, he attempts to drink the experience and memory of her away, but she has left her mark on him. Returning to her house, he finds her at the edge of the cliff. Trying to approach her, she walks backward, and eventually falls to her death. Typically, Breillat puts rationalism aside and distills—her critics would claim that she reduces—human sexuality to distinct elements that dictate what her characters say, thereby creating a form of deconstructed, almost surreal logic. Central here is that no emotion other than lust and repulsion is present: It’s the duality of sexuality. She lusts for him, not because of his physical appearance, but because she repulses him. She repulses him, not because of her physical appearance, but because of what she is. In Breillat’s world, sexuality is above the body; sex and sexuality are not necessarily the same thing. |

|

|

For instance, on the first night, the man takes a lipstick while the woman sleeps, first painting around the vagina and rectum, then around her mouth. Here Breillat suggests that all three are merely orifices. This is further underscored the second night, during which his fingering of her vagina produces a leaking liquid (saliva) in her mouth, and definitively, when he gets a rake and inserts in her ass while she sleeps.[i] Reducing the body to mere orifices, Breillat distills the motif that sexuality is beyond the body, then continues to elaborates upon in a later scene, where the woman takes a fresh tampon: “Look at it. It has the same size as a penis, I can insert it without any form of preparation and I don’t feel anything doing it. If so, why should I feel anything having sex? It is not intercourse that matters, but the act itself.” In this, to date her most brutal deconstruction of sexuality, Breillat suggests that the physical act of sex has no meaning, that only the mental act matters. Sexuality is of the mind, not of the body. Just as Breillat shows that sex and sexuality are not necessarily related, so does she touch on a theme that has been with her from her first film. In Romance X, she explored the strict distinctions between love and sex: “How can you love a man who doesn’t fuck you?” The response is significant: “I don’t like men who fuck me.” Afterward, Breillat offered this comment: “I don’t want to tell a story about people who love each other, but about people who desire each other.” |

|

But in Anatomie de l’enfer desire is a motif only by proxy. For Breillat the motif of repulsiveness is more important to explore. Noting upon disgust in the past, in Romance X the woman wonders “Why do men who are disgusted by us understand us better than those appealed by us?”, in A ma soeur! (Fat Girl, 2001) the unattractive sister states the following: “I want to lose my virginity to an ugly man, so I don’t have to remember it.”, Breillat, in Anatomie de l’enfer, makes it the central motif, as the gay man is repulsed by the female flesh, “it is deceptive in its softness”, he says, and even more by her blood.

|

|

|

Both the concept of blood, and blood itself, are significant. The man is first introduced to her blood as he walks in on her suicide attempt. Later, as he explores her vagina, his fingers are covered with vaginal secretion, and above all menstrual blood, which he forces himself to taste. When the man first feels the secretions, then smells them and ultimately tastes them, Breillat forces us to come to terms with our own sense of repulsion. Breillat elaborates on this through two flashbacks. The first features three prepubescent boys who explore the vagina of a little girl. The second features a prepubescent boy who finds a sick young bird, which he accidentally squashes to a bloody pulp. Breillat does not imply that repulsion comes from these two events in general, but offers two possible origins for the repulsion and suggests that it is rooted in our childhood. More important, she establishes blood as an index associated with guilt, by the inability to help the young bird, which is why the man helps the woman to begin with, and death and shame, by the dead young bird. |

|

|

In Anatomie de l’enfer, while explaining her menstruation, the woman dissolves a bloody tampon in a glass of water, as if making tea, and hands it to the man: “In ancient times, the men would drink the blood of their enemy to gain their strength. If you really hate me, you must drink my blood.” He drinks. Finally, after having had vaginal intercourse with her, she gushes her menstrual blood onto his penis and groin area. Repulsed by its redness, he is nevertheless intrigued by its wetness and the feel of it on his penis. One may view the process as a paradoxical intention to destroy the index of blood, noted above. Far from suggesting that homosexuality is a neurosis, Breillat suggests that repulsion is based on events beyond our control. Thus one may read him being intrigued by the menstruation blood as catharsis. I spoke briefly with Amira Casar, the female lead, about what the blood represented. She offered the following: “To me the blood is primal. You must understand that according to the catholic church, menstruation blood is unclean, impure. It is so because it is the female blood. Here, the menstruation blood is pagan, representing the woman and fertility.” Breillat often makes her characters into objects that sometimes serve only to speak Breillat’s own psychosexual thoughts. Breillat’s mise-en-scène becomes very surreal, almost like late Buñuel: deconstructed thoughts, posing instead of acting. In Anatomie de l’enfer, Breillat doesn’t direct as much as arrange poses and frames; she is the metteur en scène. Needless to say, the mise-en-scène is controlled; so controlled in fact that Breillat in the precredits notes that Casar has a body double in certain scenes of a sexual nature, and this body double is “an extension of her fictional character.” She does not hide the fact that the characters are objects: They are anonymous, known only as the man and the woman. She does little to hide that they represent her inner thoughts, going so far as to narrate the film, speaking her own words from her own book. This is not so much film as a visual presentation of Breillat’s thoughts from her book Pornocratie. Anatomie de l’enfer also marks the second collaboration between Breillat and hardcore porn actor Rocco Siffredi, aka the Italian Stallion. For Breillat, he represents the ultimate Latin lover. Her comment on why she used him in Romance X sheds light on her casting choices: “French men are so boring to look at, so skinny and pale,” she points out, while Rocco takes it in stride and jokes, “I had to fuck ten thousand women to get a part in a real film—I don’t think I could do that again.” He really isn’t a good actor, and he does nothing to pretend he is. Siffredi is very aware of his own limitations (and his advantage of an 11 inch penis). As previously noted, the characters are anonymous objects, speaking the thoughts of Breillat, and in that capacity, Siffredi represents superb casting. With Anatomie de l’enfer, Catherine Breillat has taken her exploration of sexuality to its very limit and beyond, thus reaching the end of the road she began ten films ago. Realizing that she can’t go any further, this film is to be her last on this topic—so she says now. Many are disgusted by it, indeed many hate it, but you don’t have to like her films, or for that matter agree with her ideas about or depiction of sexuality, to see that she is and has proven herself over and over again to be one of the most interesting, groundbreaking, and challenging of contemporary directors. Catherine Breillat takes a position in cinema that few dare or even have the ability to follow, and along with a handful of directors, she continues to defy conventions of normality and society to push the boundaries of cinema. She is a master and Anatomie de l’enfer is her latest masterpiece. |

CREDITS

Director: Catherine Breillat

Writer: Catherine Breillat (based on her novel: Pornocratie)

The Woman: Amira Casar

The Man: Rocco Siffredi

Running Time: 80 minutes

|

Endnotes: |

|

[i] Please note, that while “rake” in English also means libertine, among other things, it does not have this dual meaning in French, thus a paradigmatic deconstruction of the scene should be done in French, and not on the terms of the translated language. What’s important in the scene is that it’s an object inserted in an orifice. |

Recommended Reading in French Cinema (CLICK COVERS or TITLES for more information)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Films in My Life |

French Cinema: A Student's Guide by Philip Powrie, Keith Reader |

Agnes Varda by Alison Smith | Godard on Godard : Critical Writings by Jean-Luc Godard | Notes on the Cinematographer by Robert Bresson |

Robert Bresson (Cinematheque Ontario Monographs, No.

2) by James Quandt |

The Art of Cinema by Jean Cocteau |

French New Wave

by Jean Douchet, Robert Bonnono, Cedric Anger, Robert Bononno |

French Cinema: From Its Beginnings to the Present by Remi Fournier Lanzoni |

Truffaut: A Biography by Antoine do Baecque and Serge Toubiana |

Check out more in "The Library"

![]()

![]()