|

|

|

|

Review

by Brook Kennon In

1968, a small group of friends in the business of making commercials and

industrial shorts wanted to try their hands at “real” movie-making.

Given the recent explosion of the exploitation and horror film market,

led in the USA by godfather of gore, Herschel Gordon Lewis, it was

decided that a horror film stood the best chance of being seen and maybe

even making some money. George Romero and John Russo came up with an

idea, and the group scraped together just over $100,000 and got started.

With money tight, they used local talent, friends, and even investors in

the film as actors. One of the investors was a butcher who provided the

blood n’ guts for the operation. No one could have guessed that from

these humble beginnings would emerge what is, arguably, the greatest of

American horror films. A movie who’s negative was once stored in the

basement of a Pittsburgh ad agency, now resides in the Library of

Congress’ National Film Registry. |

|

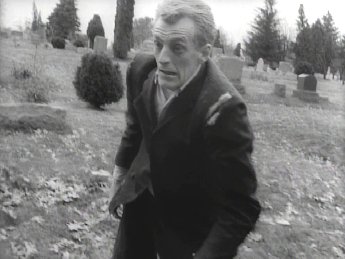

| Shot

in stark black & white, the film begins with Johnny and Barbara,

brother and sister, traveling for the annual visit a parent’s grave.

This immediately sets an oppressive mood that will be maintained

throughout. In a graveyard, the feeling of our own mortality and the

pain of lost loved ones are very close. Johnny reacts to this by making

jokes, his “they’re coming to get you Barbara” is perhaps the

films most memorable line. Barbara is saddened by her memories and

disgusted by Johnny’s lack of respect. All of that is forgotten,

though, as we see a figure in the distance, a caretaker perhaps? We

suddenly notice that the environment is devoid of sound. The figure

comes near, moving slowly but inexorably forward. His face is frozen and

expressionless. His eyes are dead. He raises his arms and attacks

Barbara. Johnny is killed in the struggle and Barbara flees. |

|

| Barbara

ends up at a farmhouse, and finding the door open rushes in, in shock

from her brother’s death and the attack. Ben, a man of action, who has

fled from town when the undead zombies, humans risen from the grave,

began an attack en masse, soon joins her. He was forced to stop because

his truck was almost out of gas. We quickly find out that they are not

alone in the house. In the basement is a relative of the farmhouse’s

owner, Tom, and his girlfriend, Judy. With them are a family, Harry and

Helen Cooper and their daughter Karen, who came here when their car ran

out of gas and a zombie bit Karen. Harry is volatile and immediately

clashes with Ben, while at the same time, the number of zombies outside

the house is growing. |

|

|

Night

of the Living Dead (NOTLD) creates its terror by making us, the

audience, feel as trapped as the seven people in the farmhouse. The

feelings of helplessness and confusion in the face of an enemy you don’t

understand are palpable. But George Romero goes even further, not

content with merely the monsters outside the house; there is also a

threat from within. The stress these characters are under results in

clashes of personality, ego, race (Ben being African-American), and the

basic human capacity for self-destruction. Like its two classic

predecessors, Alfred Hitchcock’s PSYCHO and Michael Powell’s PEEPING

TOM, NOTLD works as much a study of primal human psychology as it does

as a horror film. |

| But

make no mistake; NOTLD is nothing if not frightening. The feelings of

horror build slowly throughout the film, bursting forth on occasion, and

dropping back to give us a break, but also to continue to build in

increasing intensity. We see the zombies, slowly moving forward, having

bones broken or body parts cut off is no deterrent. They are driven to

consume human flesh, as we will later see in graphic detail. This is

contrasted by the humans in the house, frantically at work creating

defenses and finding weapons. At times working together, but just as

often Ben and Harry are at each other’s throats. The dissension within

seems to be as deadly as the terror waiting outside. |

|

|

|

The brilliance of the film, though, is in its ability to work as social commentary. It is a child of the 60’s, when American society was wrought with dissension and confusion. The Vietnam War, assassinations, race riots, civil rights; the American dream of the 50’s was quickly becoming the nightmare world of NOTLD. As in the film, society responded to these adversities, not with a “New Deal” or a WWII uniting, but with pettiness, violence, apathy, hate, and helplessness. The Cold War was at full blast and our capacity for self-destruction never more apparent. This is the brutal reality of NOTLD, where sheriffs with dogs and redneck’s hunt zombies for sport, while students and Freedom Marchers were being beaten and having water hoses turned on them in the American South. The film closes with a magnificent montage of images that drive home this black as night view of humanity as its own worst enemy. As a character will state in Romero’s equally masterful sequel, DAWN OF THE DEAD, in answer to the question who or what are the zombies, “They’re us. We’re them and they’re us.” |